When the subject is Mobility, the main challenges are very clear. Mobility shapes our cities: 50% of public space is taken by roads. It shapes our lives: 1 whole year of our life is spent in commuting. It influences the environment, causing 23% of GHG emissions in Europe, and it affects our economy, with an average of 130 million euros per year being lost due to congestion in each country.

When it comes to Barcelona, the search for such mobility solutions might seem irrelevant, considering the reputation of being an exemplary city in regard to this matter. In fact, almost half of the movements in Barcelona are done by non-motorized modes and only 21% are made by private cars. However, this small percentage causes expenses of 169 million euros per year due to congestion. And the city still deals with high rates of movement by other modes, with 6.7 million commutes every day.

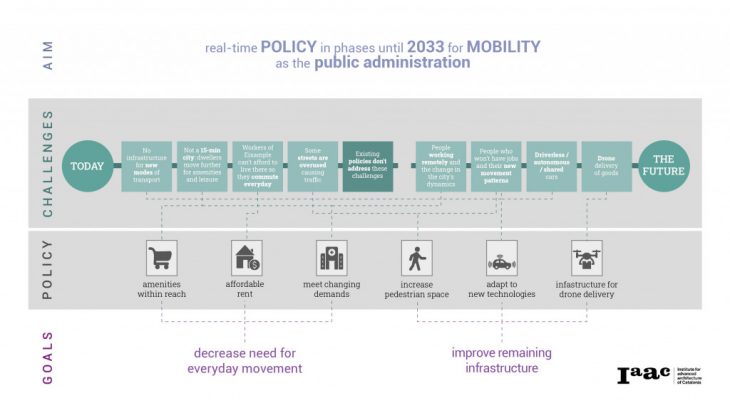

For the Barcelona case, we would like to further investigate on the Eixample district, as a prototype to be replicated in the others. Our aim with this work is to play the role of the Public Administration and build a Policy for Mobility, which is divided in phases until 2033 and is constantly updated.

THE CHALLENGES OF TODAY

What is the current mobility infrastructure?

Firstly, we investigated how the current mobility infrastructure is in the Eixample district. Therefore, we analysed the road network of Barcelona, the public transport system and the cycling network. Analyses that were based on datasets from the Municipality, TMB and OSM.

![[02. MAPS OF MOBILITY INFRASTRUCTURE IN GIF]](https://www.iaacblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/02-maps-of-mobility-infrastructure-in-gif.gif)

As a conclusion, we analysed the 10-minute walk from the public transport and cycling infrastructure, in order to check the availability of these elements around the whole area, with a positive response.

![[04. MAPS OF LAND USE ETC IN GIF]](https://www.iaacblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/03-map-of-conclusion.gif)

Why are people moving within Eixample?

Our second purpose was to understand the causes of the constant movement. Which led us to two analyses, based on the movement within and towards Eixample.

For determining why people are moving within Eixample, we firstly analyzed the quantity of amenities that exist on a 15-minute walk radius for each neighborhood, also assessing the availability of these services in each street. Then, by evaluating the land uses, we have captured the characteristics of the entire district and in particular the lack of green areas in a part of the city which is so populated. These analyses have been possible using the dataset of Barcelona Activities provided by InAtlas, combined with data from OSM.

![[04. MAPS OF LAND USE ETC IN GIF]](https://www.iaacblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/04-maps-of-land-use-etc-in-gif.gif)

In conclusion, we could say that the reasons behind people’s movement within Eixample are mainly related to the lack of green areas and a lower concentration of amenities in confined zones, reasons which force dwellers to move further for such necessities.

![[05. CONCLUSION MAP]](https://www.iaacblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/05-conclusion-map-730x518.jpg)

Why are people moving to Eixample?

On the other hand, we would like to investigate why people are constantly moving to Eixample? The everyday movement is closely linked to the need of commuting to work.

So firstly, we were able to assess the number of people who work in Eixample, from the CensoEmpresas dataset, and identify that their concentration is mainly around Passeig de Gracia Street. Then, we analyzed the origin of these workers with Mobility INE dataset, evaluating where employees of Eixample are coming from. We identified the percentage of people from other neighborhoods coming to work, and together with data from RFD, we were able to assess their income. Based on this and additional information, we were able to compare and visually represent that the income of the workers is usually lower than the income of the dwellers.

![[06. MAPS OF RENT ETC IN GIF]](https://www.iaacblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/06-maps-of-rent-etc-in-gif.gif)

Thus, our conclusion to why workers commute to Eixample every day is mainly because they can’t afford to live there. Based on relevant studies and considering the average income of workers and dwellers of each neighborhood, we can calculate a suggested maximum rent price per room they could all afford. Furthermore, considering these prices, we can identify that the unaffordable places for rent represent a very large amount of the district’s housing options.

![[07. CONCLUSION MAP]](https://www.iaacblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/07-conclusion-map-730x518.jpg)

What are the mobility patterns?

Moreover, we would like to understand the exact way people move, and for analyzing patterns, it is necessary to look at movements but also stops. Based on our investigations, we infer that weekdays mobility mainly consists of going for work and study. Therefore, with Spanish Inspire Catastral and OSM we were able to identify the location of offices, schools and universities, and cross this information with weekday’s people’s movements acquired from Footfall Data analysis. Whereas for the weekend’s mobility, we infer that it mainly consists of going for non-everyday needs, such as amenities and leisure as well as tourist attractions. In both cases, we can analyze the concentration of people’s movement in each street during the weekend, and identify the main zones they go for these services.

Then, after further filtering of the Footfall Data, we analyzed only the shortest movements in order to assess the people who are most likely moving on foot or by bike, and analyze which routes they are taking. In this way we can identify the pedestrians’ and cyclists’ patterns.

![[08. MAPS OF FOOTFALL IN A GIF]](https://www.iaacblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/08-maps-of-footfall-in-a-gif.gif)

So the conclusion of all these pattern analysis is the identification of the most commuted streets and the streets most used by pedestrians and cyclists.

![[09. CONCLUSION MAP]](https://www.iaacblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/09-conclusion-map-730x518.jpg)

What has been done by the Public Administration?

Lastly, after analyzing the Challenges of mobility in Eixample today, we researched what the Public Administration has been doing towards the topic. The most important local policy is the Urban Mobility Plan (PMU) of Barcelona, the two latest ones being for 2018 and 2024. Both policies rely a lot on the implementation of the Superblock Project and how this will be responsible for increasing the area for pedestrians and cyclists mobility.

However, our conclusion from analyzing the policies is firstly that it represents an engineer’s perspective of mobility, focusing only on proposals for the means of transport, without actually looking into the causes of the problem, for example, the reasons for commuting and how to mitigate it. Also, it implements the Mobility As A Service integrating all modes in one platform, but Smart Mobility is much broader than this, and should also take into consideration the new means of transport arising. And lastly, although the Superblock project poses a good strategy, it is not adequate for the long-term future.

THE CHALLENGES OF THE FUTURE

And what will be the Challenges of mobility in the future? Based on sources, we made some assumptions.

With Covid and the urge to work remotely, we see a permanent change in the city’s dynamics, and by 2025, 25% of the World’s workforce will be working from home, which will result in a similar amount of workspaces becoming vacant. By 2030, as technology replaces manual labor and economies change, 50% of people won’t have jobs, but consequently the government will provide people with financial support through a Basic Income, and a shift in movement patterns will occur: movements for amenities and leisure will overcome the number of movements for work and study. On the other hand, new means of transport will emerge, and over 50% of cars will be driverless, while 40% of rides will be shared, which will drastically reduce the space needed for cars, as well as the GHG emissions. Lastly, by 2033, drones will be used for all deliveries, and as a repercussion, a new mobility network will appear in the sky.

OUR POLICY

The Future is On Demand

So how are we shaping our policy to address the Challenges of today and the Challenges we assume for the future? We divided our proposals in 3 main phases, which are intended to be revised in almost real-time, with the policy being constantly updated based on continuous re-analysis of the current situation of mobility. Furthermore, the concept of Policy on demand is not only related to a policy that adapts through time and different needs, but to citizens’ actual needs informed through a participatory process.

![[10. PROPOSAL DIAGRAM]](https://www.iaacblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/10-proposal-diagram-01-730x353.jpg)

The Future is Participatory

The participatory process will happen with citizens’ engagement both online, directly through the City Platform, and offline, through kiosks on site. It will be used for them to inform the leisure spaces and amenities needed in their surroundings, promoting not only a 15-minute neighborhood but a much closer one.

![[11. PARTICIPATORY DIAGRAM]](https://www.iaacblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/11-participatory-diagram-730x286.jpg)

PHASE 1: The Future is Accessibility

Firstly, in 2025, we’ll be dealing with changes on the city’s dynamics and the appearance of new vacant spaces. So how will the street change from today until 2025?

First of all, these vacant offices will become the amenities needed in each block according to the Land Use permissions established through the participatory process. The same goes for leisure, replacing existing parking spots with Parklets. The green leisure spaces will also be increased by reclaiming the inside area of blocks and turning them into public plazas, similar to Cerda’s original plan. Lastly, we will make housing affordable for the workers through a regulation for rent price reduction based on their income and how much they could afford to pay.

![[13. 2025 MAP GIF]](https://www.iaacblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/13-2025-map-gif-730x460.jpg)

PHASE 2: The Future is Smart Mobility

![[14. 2030 SECTION GIF]](https://www.iaacblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/14-2030-section-gif.gif)

In 2030, we’ll have a shift in the movement patterns as well as more urban spaces available which once belonged to the cars. So how will the street change in this scenario?

While our plan for 2021 to 2025 was focused on decreasing the need for moving, now we focus mainly on the street network itself. Firstly, between 2025 and 2030 we stimulate the new means of transport by establishing streets for driverless cars, based on the less busy ones from our analysis. AI will be used to make the street network flexible and constantly changing, considering that driverless streets can stop operating when needed. Also, we take the decreasing space dedicated to cars back to people, by implementing the Superblock pedestrian streets in the first stage.

Then, when we reach 2030, we increase the amount of pedestrian space to 50% of the street network, based on the analysis of streets most used by them. We will also promote a smart public transport system, with driverless tourist and public buses, and a public transport that operates on demand adapting to users’ requests on the TMB app. Furthermore, considering the empty parking lots, we propose that the ones located on the remaining streets for cars, the busiest ones of the district, will be sold to the City to provide parking, electric charging and other infrastructure for the new modes. The income from private drivers and companies using this infrastructure will finance the new transport system. The other parking lots will be under the Land Use Permits established on the participatory process, to meet the changing demands and provide the amenities needed in each block.

![[15. 2030 MAP GIF]](https://www.iaacblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/15-2030-map-gif.gif)

PHASE 3: The Future is Flying

![[16. 2033 SECTION GIF]](https://www.iaacblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/16-2033-section-gif.gif)

In 2033, a regulation for the new mobility network in the sky is needed. So how will the street change in this scenario?

While our previous phases were focused on people’s mobility, the last phase focuses mainly on goods’ transportation. Firstly, we start this phase of our policy also in 2025, when drones will probably begin appearing. At this moment, while the drone delivery system is still arising, we will establish a temporary goods distribution with driverless trucks, promoting a tax reduction for companies that use this mode of transport. We will establish the largest car and driverless car streets as the main goods routes, for all types of trucks, and the smaller ones as a secondary route only for driverless ones.

Then, we will regulate the system of drones by restricting the heights and operating hours to minimize disturbance. The public inside area of blocks will be used as the delivery centers for them. The drones, which belong to private companies, will only be allowed to fly if they make them available for the public administration when necessary. Moreover, in this initial moment, only essential needs will be allowed to be delivered by drones, as a first stage of implementation. Gradually, more drones will appear and less driverless trucks will be used, and when we reach 2033, drones will be used for delivering all goods, with driverless trucks serving only as a support.

![[17. 2033 MAP GIF]](https://www.iaacblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/17-2033-map-gif.gif)

SUPERBLOCKS x HYPERBLOCKS

At last, as a conclusion we would like to state that our vision for the district is a step further from the Superblock. A vision we would like to call: the Hyperblock. While the Superblock focuses mainly on the street network, ours consider the reasons for mobility and change beyond the network itself. Also, the city council proposes just a few public green spaces, not meeting the current demands, whereas we propose one in almost every block and street. And while their proposal doesn’t consider new means of transport and have limited amounts of pedestrian space, we introduce new technologies and prioritize the pedestrian.

![[18. CITY COUNCIL COMPARISON]](https://www.iaacblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/18-city-council-comparison.gif)

Which means, in the end, that the streets will be changing throughout time, according to the demands of today and the future, in a way we mitigate the cause of mobility challenges and improve its infrastructure, in a vision that, indeed, embraces the people’s participation.

Hyperblock: The Future of Mobility is a project of IAAC, Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia developed at Master in City & Technology in 2020/21 by students: Diana Roussi, Laura Guimarães, Matteo Murat, Sridhar Subramani & Stephania Kousoula and faculty: Luis Falcon & Iacopo Neri.