Breaking the Boundaries

Yokohama Ferry Terminal

“An attempt to dissolve the sugar of architecture into the water of nature.”

1. Breaking the boundaries from nomadic practices & their non-formal parameters to an architecture of ‘formless’

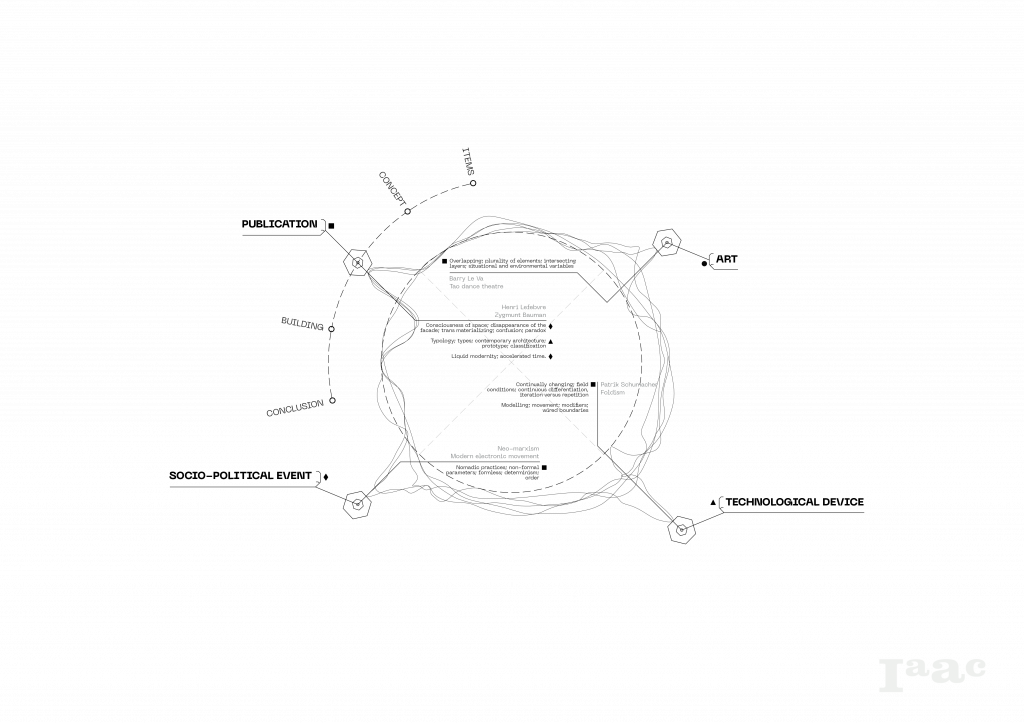

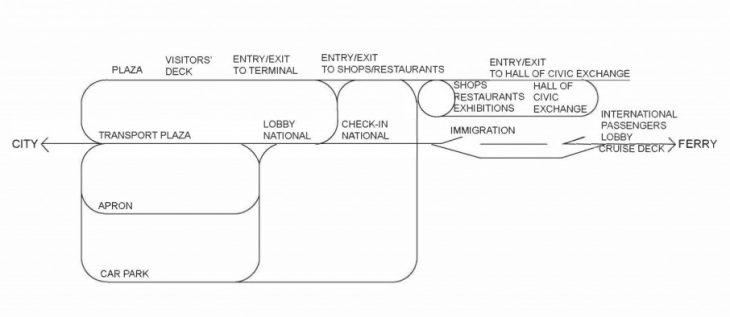

The project for the Yokohama Ferry Terminal is described as an undetected systemic process defined by Non-Formal Parameters, as opposed to others based on Form, determinism, and order. This change in paradigm arises in the 1960s and according to Alejandro Zaera, architects and artists have been trying to study for nearly two generations the evolutionary and emergency processes of the form. The use of the term “formless” is not intended to negate form but simply that this is the result of an open and indenter morphogenetic process-undermine. Therefore, the Yokohama project is generated from a diagram of feedback circulations as a continuous loop between the city and the ferry, between passengers and goods, between national departures, etc…

Circulation Diagram Yokohama Ferry Terminal

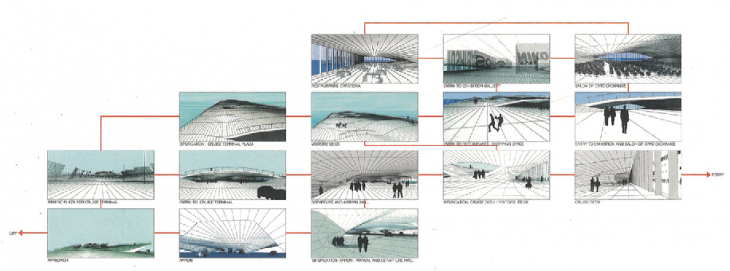

Diagram of the circulation by images, going from space to space

2. Breaking the boundaries from the conventional understanding of the consciousness of space & facade to an architecture of trans materializing; confusion & paradox

In the book The Production of Space, where the author, Henri Lefebvre speaks explicitly of the “disappearance of the facade” in 20th-century avant-garde architecture. The writing relates to the moment when Ingraham describes the design of the Yokohama Ferry Terminal as an architecture that does not require a face. This idea, of disappearance, accompanied for several years this research while studying precisely the reduction of the facade to its minimum expression: a skin that disappears, transparent, a wall capable of trans materializing.

‘’In calling their Yokohama Ferry Terminal ‘an architecture without exteriors’ Foreign Office Architects perhaps meant that they were no longer thinking of architecture as a material articulation of the relation between interior and exterior space; no longer thinking that architecture needed a face or a façade. Architecture would be, rather, a skin-surface with multiple possibilities that made no meaningful distinction between inside and outside.’’

- ‘‘A new consciousness of space merged whereby space (an object in its surroundings) was explored… by deliberately reducing it to its outline or plan into the flat surface…

- The façade… disappeared…

- Global space established itself in the abstract as a void waiting to be filled, as a medium waiting to be colonized by commercial images, signs, and objects… The ‘signifier-signified’ relationship conflicts into general transparency, into a one-dimensional present and onto an as it were ‘pure’ surface… Thus space appears solely in its reduced forms. Volume leaves the field to the surface, and any other overall view surrenders to visual signals spaced out along fixed trajectories already laid down in the plan. An extraordinary –indeed unthinkable, impossible- confusion gradually arises between space and surface, with the latter determining a spatial abstraction which is endowed with half-imaginary, half-real existence.’’

3. Breaking the boundaries from the conventional interpretation of plurality of elements, overlapping; intersecting layers to an architecture-dependent on situational and environmental variables

Therefore, in the case of the Yokohama Ferry Terminal, the confusion of the individual gradually arises when there is no clear delimitation of the ground between the interior and exterior space. Consequently, the ground becomes a paradox. The paradox resulted from the overlapping of the plurality of elements present in Yokahama Ferry Terminal it is also highlighted in arts, particularly Barry Le Va’s pioneering of early floor sculptures from the late 1960s.

One of his Off Center, Off Center (Variation 15) (1969 – Present) is a stack of multiple glass sheets, arranged in intersecting layers, which are then shattered at regular intervals with a sledgehammer. The clear glass is penetrated with sinuous cracks that begin at the centralized point of impact and contrast directly with the straight edges of the glass sheets. Le Va first used glass in his installations in the 1960s. Despite the work’s precise parameters, situational and environmental variables result in a unique and site-specific installation every time it is presented.

4. Breaking the boundaries from the conventional, rigid understanding of types & classification to an abstract architecture of prototypes & ‘sameness’

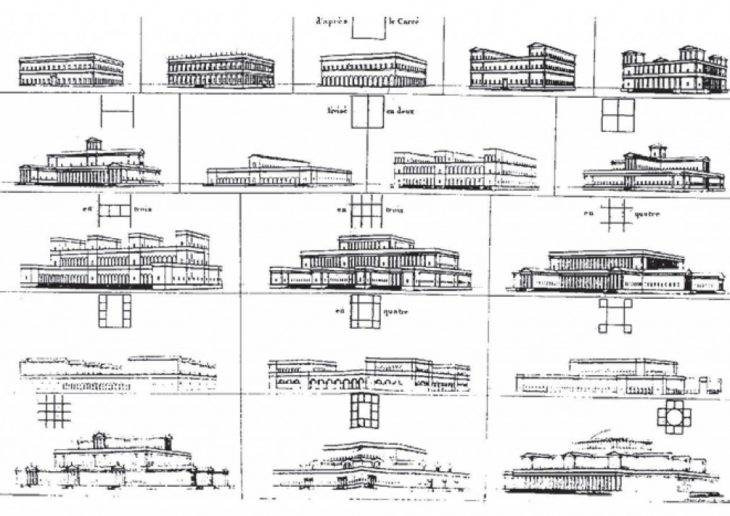

It is claimed that the use of ‘type’6 -the process, classification, and systematization- as a tool in the design process has led to the ‘typification’6 of design that discourages the emergence of new formal structures. Originally, typology has been defined variously as the imitation and reproduction of exemplary precedents (Quatre ere, Rossi), the formation of types through a composition of elements according to manuals (Durand, Krier), and as the repeated application of design norms under universal conditions (Gropius, Le Corbusier). Contrastingly, contemporary architecture focuses on a typology that is not confined to a fixed type or a specific structure associated with a program. Rather, the value of typology exists in a process that begins with a type in a flexible context that can be proliferated in multiple locations regardless of its typical relationship with forms.

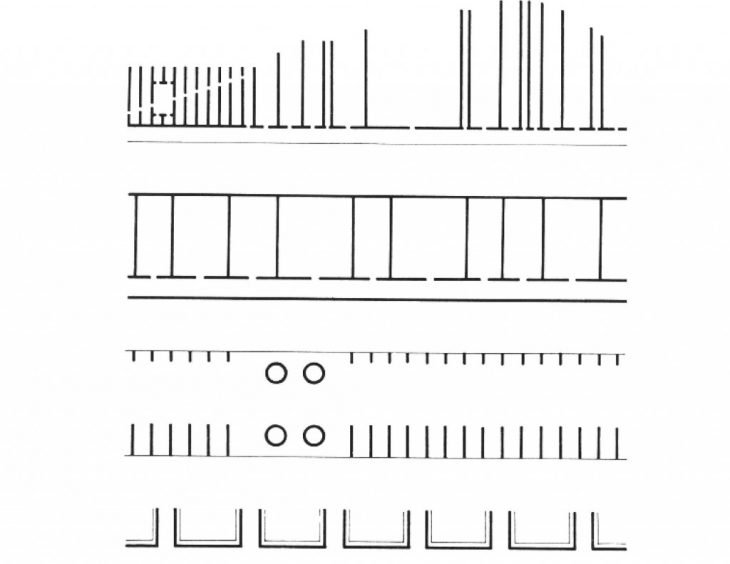

Composition by types of a building by J.N.L. Durand

Reduction of Traditional Forms By Aldo Rossi

The works of FOA provide a clue to redefining and reinterpreting the subject of typology, which enables us to operate appropriately in constantly shifting environments. Particularly, in the search for the production tool for a new norm, FOA has considered types by extracting special kinds of information—thereby making the types abstract —and restructuring it within a project as a “prototype”, leading to making architecture based on composition in the case of Yokahama project. Finally, while classical typology fundamentally involves the concept of “repetition and reproduction”7, FOA emphasizes the logic of “identity or sameness”7 in contemporary architecture.

Topological Structure By FOA

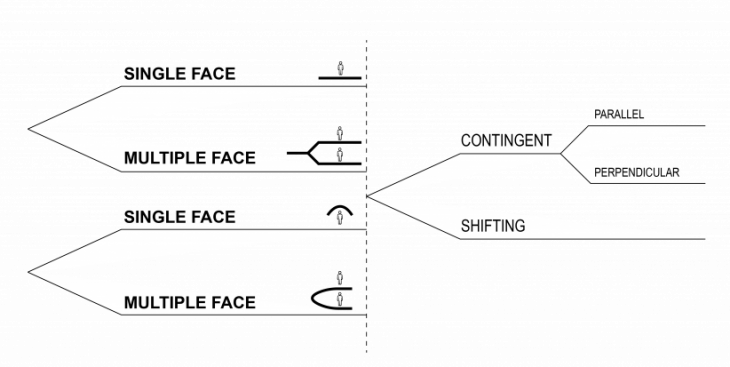

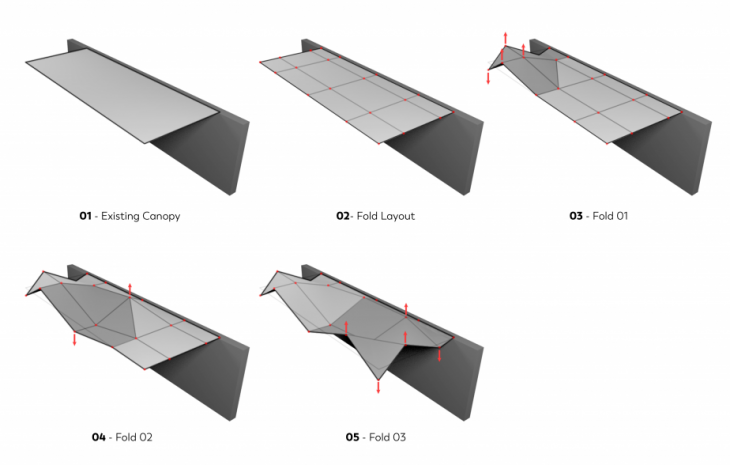

5. Breaking the boundaries from the conventional interpretation of continually changing field conditions to a design process characterized by continuous differentiation, iteration/repetition, and even deconstructivism

Recently, “Foldism” – one of the initial phenomena of Parametricism, defined by Patrik Schumacher, establishes a continually changing and potentially responsive formal condition, in spaces and urban environments. Similarly to Yokohama Ferry Terminal, folding architecture emphasis the rules of field conditions, continuous differentiation, iteration versus repetition, the slogans from part to particle and from typology to topology, and more concretely the concept of a single surface project. (Schumacher, Patrik). Furthermore, the concept of foldism includes another degree of multifaceted nature and dynamism to the typology as opposed to adding layers and parts to the framework as if there should arise an occurrence of deconstructivism., this framework can take a solitary surface and separate with a versatile and liquid point framework that merges with relevant highlights bringing about an intensive variation.

Foldism Diagram

6. Breaking the boundaries from conventional modeling, movement, simulations, and delivering capacities to an architecture of modifiers and wired boundaries

When discussing foldism within the field of technological methodology, 3DS Max which was first presented as 3D Studio in the late 90s is a parametric 3D modeling software that provides modeling, movement, simulations, and delivering capacities for films, games as well as in the field of architecture. 3ds Max utilizes the idea of modifiers and wired boundaries to control its calculation and enables the client to content its usefulness. With the presentation of T-splines and poly modeling within the software, It turned out to be a lot of receptive to identify with calculations which included differentiated and complex networks a lot of like the Yokahama Terminal.

7. Breaking the boundaries from the conventional interpretation of frozen motion to an architecture of the accelerated time

However great the temptation exerted by computer animations, architecture remains, to paraphrase Goethe, frozen motion. FOA’s Yokohama Ferry Terminal must emphasize not merely to the time and the history of a project but to its accelerated time, to its micro-history, in an attempt to dissolve the sugar of architecture into the water of nature. The principle of fluidity manifests as a spatial continuity that is generated from a section of oblique planes in the case of Yokohama Port Terminal, and finally, it is presented as a dynamic – in its three dimensions, where the idea of nature connects with that of the cave and a space that flows like a liquid.

8. Breaking the boundaries from the conventional understanding of social responsibility and shared urban spaces to an emergent typology of transportation infrastructure

Finally, it may be concluded that the Yokohama project is a key part of a new change in paradigm within the architectural thinking of the 1960s. The futuristic terminal represents an emergent typology of transportation infrastructure. Its radical, hyper-technological design explores new frontiers of architectural form and simultaneously, provoking a powerful discourse in regards to the social responsibility of large-scale projects to enrich shared urban spaces.

9. Bibliography:

Lefebvre, H., & Nicholson-Smith, D. (2011). The production of space. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell

FOA (2004), Phylogenesis FOA’s Ark, Barcelona: Actar publication

Bauman, Z. (2015). Liquid modernity. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Ingraham, C. T. (2006). Architecture, animal, human: The asymmetrical condition. London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

Ito?, T., Cecilia, F. M., & Levene, R. C. (2009). Toyo Ito, 2005-2009: Espacio li?quido = liquid space. Madrid: El Croquis Editorial.

Rossi, A., Ghirardo, D., Ockman, J., & Eisenman, P. (1984). The architecture of the city. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Zaera, A., & Keeney, G. (2012). The sniper’s log: Architectural chronicles of Generation-X. Barcelona: Actar.

Im, Jonghoon, and Jiae Han. Typological Design Strategy of FOA?s Architecture (blog), 2018.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.3130/jaabe.14.443.

Schumacher, Patrik. “Design as Second Nature.” Patrikschumacher.com (blog), 2018.

https://www.patrikschumacher.com/Texts/Design%20as%20Second%20Nature.html.

Schumacher, Patrik. “DIGITAL – The ‘Digital’ in Architecture and Design.”

http://www.patrikschumacher.com/,

2019.

http://www.patrikschumacher.com/.

Breaking The Boundaries – Yokohama Ferry Terminal is a project of IaaC, Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia developed at the Master in Advanced Architecture in 2020/2021 by Students: Alexander Dommershausen, Iulia Maria Lichwar, Aman, Sasan, Stefanie Thaller, Ziyad Wassef Abdelkader Youssef Ahmed

Faculty: Manuel Gausa, Jordi Vivaldi Piera