There is no need to be interested in timber construction to notice that we find ourselves in a material shift in the AEC industry. Images of wooden buildings are more and more common in architecture and design websites and publications. Mass timber construction is increasing all over the world, prompting architects, designers, and real estate developers to jump on this trend. In a context of climate emergency, the use of mass timber as a structural material is seen as a way of reducing the environmental impact of the building industry, which today accounts for 40% of the global carbon footprint. Since trees absorb CO2 to grow, buildings made of wood become carbon sinks, and moreover, the use of timber also means that other carbon intensive materials, like cement or steel, are reduced as part of the substitution effect.

The role of forests

Forests are essential for our survival (and not the reverse), as the EU has already acknowledged in numerous reports and in making them an essential part of its strategy and Agenda 2030 to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. We need the forests to sequester CO2, and with wood products like engineered wood products, we can create timber buildings that stock this carbon. As designers and consumers at the end of the production chain, there is a risk that we perceive timber detached of its material source: forests and trees. They are not only a material resource, but also an environmental and social asset hosting complex ecology systems. If timber consumption favors tree species with rapid growth, there is a risk that forests will turn into plantations, becoming more vulnerable to the hazards triggered by climate change such as fires, windstorms, or plagues, and change the landscapes that characterize our countries.

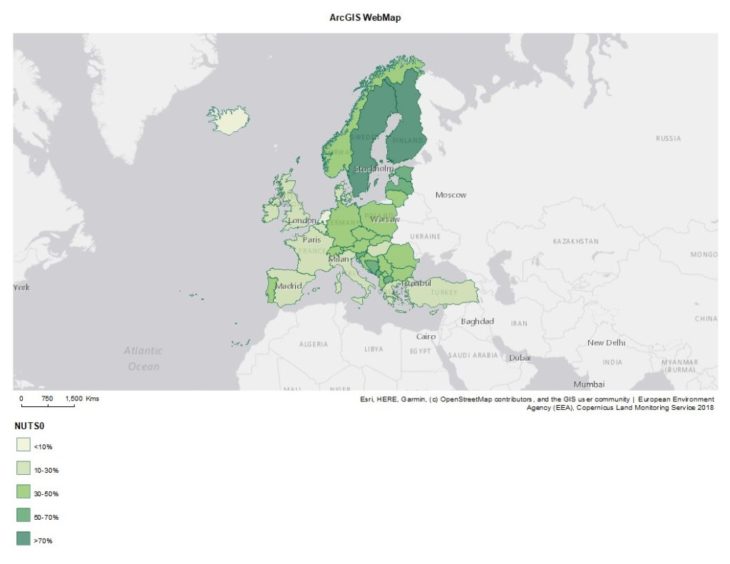

European forest cover. Source: Forest Information System for Europe (FISE)

Most of the sawn wood products used in Europe come from European forests, and since the application of the European Timber Regulation (EUTR) in 2013, all wood must be FSC or PEFC certified, which means it comes from sustainably managed forests. Although the term “sustainably managed forestry” can seem like a contradiction, we must understand that harvesting the forest to get timber is not equal to deforestation, when done in a sustainably managed way. In addition, Europe is not using more forest than what it has. A study from 2017 estimates that if all new buildings in Europe were to be built with wood, that would claim as much as 50% of Europe’s annual forest growth.

Forest plantations and management

European forests are today a mix between natural forests and plantations. Forest plantations, which are actively managed forests predominantly composed by planted trees, are a key element of the EU Forest Strategy in the fight against climate change. They can increase or restore a land’s forest area and biodiversity, and they contribute to carbon sequestration. It has been documented that the largest carbon sinks are the ones created by young trees in newly planted or deforested areas. Thus, even if ancient forests can assure a steady carbon sequestration, it is managed plantations that will provide the maximum carbon storage, since trees need more CO2 while they are growing than in their full-grown state. Managed forest plantations are also a mechanism for avoiding deforestation or enlarging a land’s forest cover, but they also come with risks. Plantations can diminish the natural biodiversity of the forest if there is no variation of tree species, since less diverse forests are more vulnerable to the hazards triggered by climate change, like plagues, droughts, or wildfires. This happens, for example, if plantations are meant to favor one tree species of rapid growth, or one that produces easily marketable wood. Therefore, if plantations are only aimed at producing one type of tree species, we will most likely loose forest ecosystems as we know them

Fallen trees in the Swedish landscape.

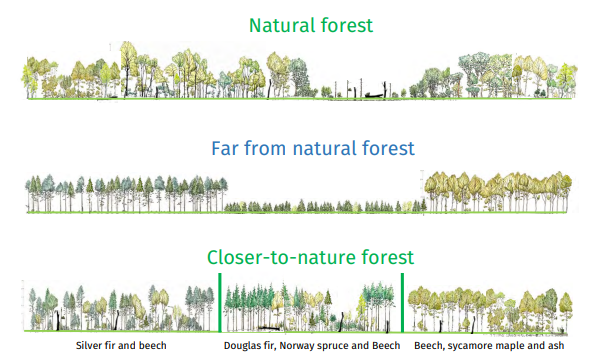

To tackle this, EU proposes to adopt the practice of Closer-to-nature forest management. Closer-to-Nature forest management is based in the principles of sustainable forest management (SFM) and it is a model already applied in 22-30% of forest area in Europe. In countries like Switzerland, Slovenia and some German states it represents 100% of the forest management. EFI considers Closer-to-Nature forest management as an “umbrella” that covers all approaches that support biodiversity, resilience and climate adaptation of the forests under the principles of SFM. It promotes native species as well as site-adapted non-native species and natural tree regeneration, it protects special tree habitats, supports the landscape dynamics, and avoids intensive management operations, supporting a continuous forest landscape with partial harvests.

Illustrative image showing the difference between a natural forest (top) an intensively managed forest for wood production (middle) and a closer-to-nature managed forest (bottom). Source: European Forest Institute (EFI)

We design the forest

We need more forests, but we need well planned forests, that protect endangered local species while introducing new trees to support the existing ecosystems. It is not enough with just planting trees, as the environments we will produce may be green, but not pleasant or prepared for the coming climate conditions. As Jane Hutton explains in her beautifully written article Specifying Wood(s), as architects and designers, we have the power to specify which type of wood we are using for our projects. Even though replacing traditional materials for wood is already a big step in the race against climate change, we need to be aware that by choosing one or another type of wood, we will create different outcomes in the forests’ ecosystems, and we will be encouraging one or another management model. Choosing locally sourced wood from sustainably managed forests is the best way to guarantee that our forests will be environments with rich biodiversity.

Who designs the forest? – Forest management and timber construction is a project of IAAC, Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia developed for MMTD in 2022 by student Maria Cotela Dalmau. Faculty: Daniel Ibáñez. Course: Narratives