A COURSE WALKS INTO A BAR…

INTRODUCTION

The way we design and build our environment is changing. New technology is making it possible for us to create smarter, more sustainable, and more livable spaces. And, as we become more connected, we are also seeing the rise of a new kind of democracy in the way we design and manage our built environment.

Today, there are a number of powerful tools that allow us to collect data about how our cities function, and to share that information with a wider audience. We can use sensors to track everything from traffic patterns to energy use, and we can use online platforms to engage directly with citizens. This data is helping us to make better decisions about how to design and operate our urban infrastructure.

Broadly, our interest for this research has been in the psychological and societal role that the built environment plays in our daily lives; how technology affects this; and, despite the reticence of the construction sector to modernise, how changing technology is changing the way we relate to that built environment.

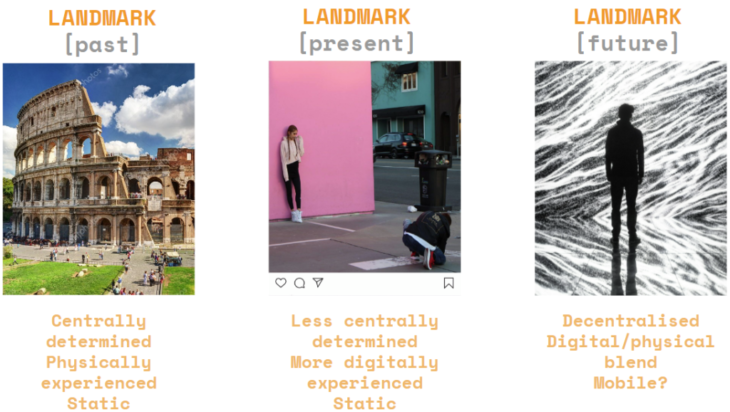

LANDMARKS OF THE PAST, PRESENT & FUTURE

Initially we were drawn to the idea of ‘landmark’, viewing it as a kind of punctuation point in a landscape that could otherwise be bewilderingly continuous. That lead us to beging to looking at what ‘landmark’ meant in the past, present and future.

Landmarks of the past tended to be defined in a top-down manner – in urban centres, a person in power, such as a monarch or a politician, would usually have decreed what constituted a landmark. Landmarks were physically experienced and static: buildings like the coliseum; Nelson’s column; a palace.

In the present day, as people are increasingly interacting online, landmarks have started to move from the physical world into the digital. Parameters that affect the digital are therefore being sought out in the physical world, and this is altering what we consider to be a landmark. In Los Angeles, for example, the side of a Paul Smith store is painted a tone of pink which looks particularly eye-catching on an Instagram grid of images, and people travel to this physical site specifically to capture it for their digital identities. The importance is such that the Paul Smith store has admitted to spending $60,000 per year to upkeep the shade of pink.

We observed that present day landmarks were more digitally experienced than before, but still largely a physical thing, which was static. The definition of a landmark was more decentralised than in the past – the power of identification was shifting to a more bottom-up model, in which a landmark started to be recognised on the basis of how many individuals recognised or acknowledged it digitally.

Extrapolating these observations, we wondered whether a future landmark would be entirely decentralised, and perhaps even entirely online, with no physical component. Perhaps it might be a blend of the physical and the digital, with components in each. It might even be mobile, in that people experiencing it could have different geophysical locations, or in motion. [As an aside, the physical components of digital objects are always present, even if only in the noisy, energy-consuming server centres hidden in less populated areas.]

LANDMARK VS MONUMENT VS PLACEMAKING

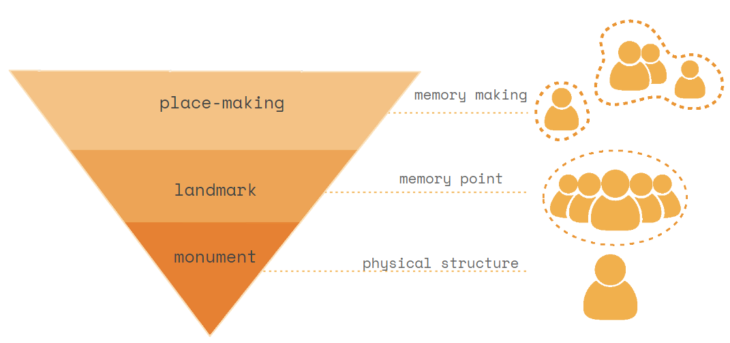

In the course of the research we deduced a distinction between landmark, monument and placemaking.

MONUMENT: a physical structure, most often decreed by a single person or few people from a place of power. A top-down identification. The Luxor obelisks would be an example.

LANDMARK: a landmark is a memory point, recognised by a group of people (as individuals or a group). It might be the Luxor obelisks, but equally it could be a giant illuminated logo sign which people commonly use for wayfinding in a city. The landmark is shared amongst people, and commonly acknowledged by a group.

PLACEMAKING: when multiple people create memory points that populate a place in their relationship to it. These might be the same as other people’s memories, or they might be private.

We realised a more appropriate focus to our question was not the objects within the landscape, but on this human element, and how humans related to their built environment. We formulated an initial research question:

How is technology shaping the democratisation of the design of our built environment?

How can it?

APPROACH

While thinking about what methods we could use to possibly allow everyone to participate in the design process, we tried to find skills that most humans shared with one other. We narrowed it down to language and digital literacy, the former since we can assume that most of the world’s population speaks at least one language and the latter because it’s use is increasing drastically and almost becoming as ubiquitous as language in developed countries.

LANGUAGE

Since most people could use language to express themselves, we hypothesised a process in which we could either survey people on their idea of a landmark or scrape that data from their online descriptions of landmarks. We would then use Natural Language Processing to extract the keywords and input them into a Style-GAN which would generate a collective idea of what a landmark would be.

However we decided against this method as it would be extremely difficult to identify biases in what people are saying and the actual output of the GAN. GANs are also still far from perfect and years of reseach still needs to be made in order to output reliable results.

“… kaleidoscope colors illuminated into the church”

THE DISCRETE ARCHITECTURE

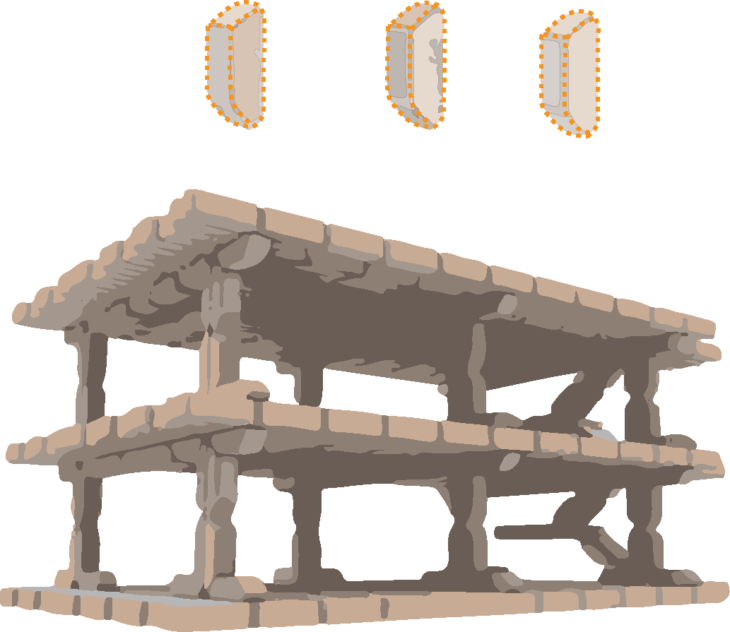

Discrete Architecture seeks to take the first step in using automation to confront the biases and privileges both inherited by and inherent to the disciplines of the built environment

It is a prototypical and combinatorial approach of building, creating discrete set of tectonic building elements to be assembled/disassembled–and form heterogeneity.

There is a strong belief that automation will provide the ground for discreteness to innovate the architecture and construction field.

A COURSE WALKS INTO A BAR

One approach to this question is that taken by the discrete architecture movement, which addresses automation as a key component to aiding in the democratisation of the building process.

Our objective is foster a discussion on our research question from the framework of discrete by bringing o bring different people to the table. Or… a bar

Introduction

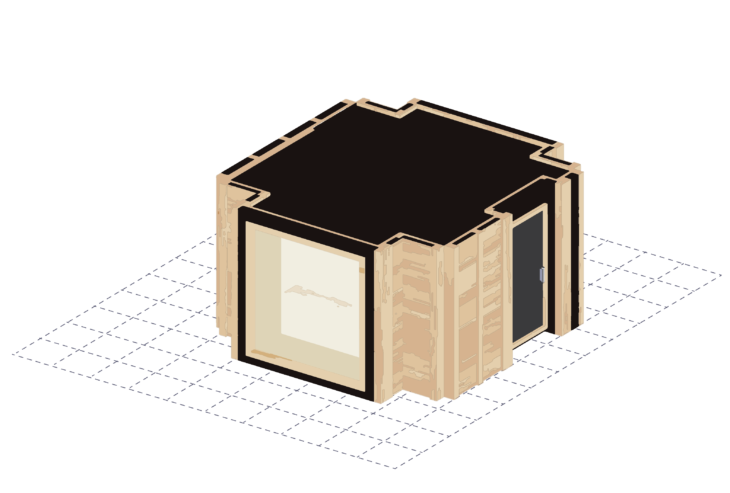

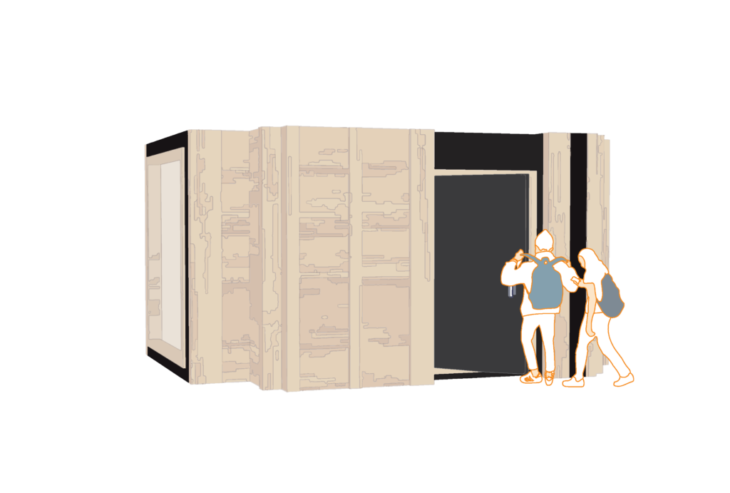

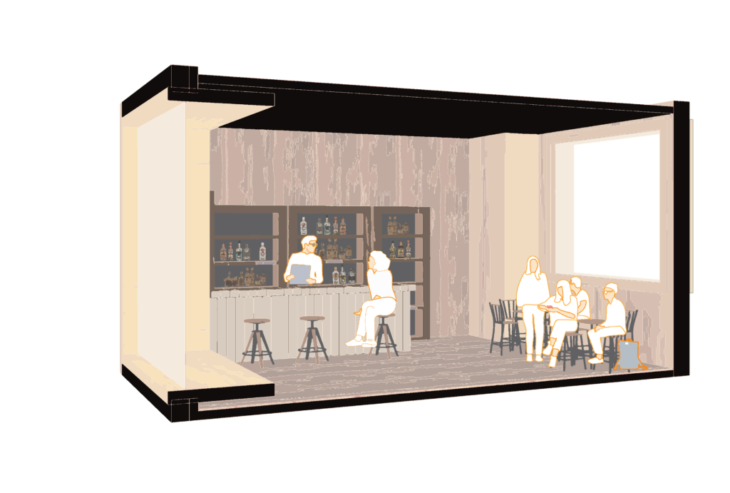

It’s a rainy afternoon and the students’ usual bar under the bridge is packed. Across the street, they see a highly-designed timber shed that finally put up a bar sign a few days back.

There, in the dimly lit construction with minimal HVAC, they congregate to discuss the conclusion of their week and reflect on the meaning of their studies.

STUDENTS: Is this place new?

OWNER: Yes!

MANAGER: …and no. It’s not finished yet.

OWNER: It’s the beginning of a movement. It’s here to inspire. It doesn’t have to be finished yet.

STUDENTS: What’s special about it?

OWNER: You see these blocks? They’re all robotically fabricated in a warehouse, then assembled here on site.

DREAM OF FORDISM

The students become engaged, as they reveal to the owner that they are studying robotics. Witnessing their interest, the OWNER begins:

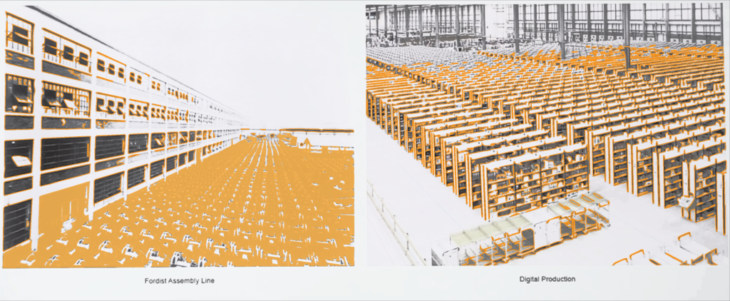

OWNER:You’ve seen pictures of the Ford factories in the US in the 1900s, right? That’s what we used to think technological futures looked like. Endless rows of the same products, organised by boxes, lines, grids. That architecture of mass production gave form to the architecture that developed around it.

It came with great promise of empowerment for the masses – and it worked, in some ways. Fordism brought a market accessibility previously only available to the rich. But it was so inflexible, and people don’t always want the same thing. The dream broke apart.

We’re always on the lookout for new futuristic forms in architecture, but the future that technology has brought us actually looks far more like those Ford factories – the endless rows of products of the Amazon warehouse. The form is the same. What’s changed is the system of organisation underneath it.

Products now vary, but even the most banal are organised with an algorithmic logic – an inhuman analysis of our human capitalist desires.

Digital arrangements are already deeply embedded in our society. The only significant sector where that’s missing is construction. And we already design with digital. We just don’t build with it.

With discrete architecture, we can.

FOR THE COMMONS

The owner waited to hear what the students might have to say.

Curled over the bar, the drunk guy abruptly raises his head.

DRUNK GUY: Oh come on. What makes you any different from prefab?

MANAGER:Prefab is still far more in the world of mass production. What we’re talking about here is the ability of technology to bring us mass customisation.

Building components are fabricated off-site in the same way, yes. We keep the efficiency of that model: less transport, less site logistics, more streamlined construction making everything lower risk and lower cost.

Where it differs is that discrete architecture allows people to engage in the design and assembly process. Unlike prefab, unlike any other architectural movement that’s come before, it facilitates a democratisation of the built environment. By using timber modules such as the ones you see here, we streamline production and make bespoke design available to all.

This bar is just a start. But I dream of a future where everyone can get hands on with building and directly participate. We can remove barriers to engagement through digital interfaces such as game platforms. Then if we can use algorithms to optimise the pattern in which the discrete pieces reliably come together, the design process can even be completely open source – and create a natural diversity in our built environment.

AND WHAT OF AESTHETICS

dragging her heavy steel broom, the cleaner couldn’t help but to intervene:

CLEANER: But won’t everything just look the same? If it’s all made of these same wooden blocks? I don’t want to live in a house that looks like this bar. It is easy to clean though, I give you that. Not much detailing.

MANAGER: Democratisation wouldn’t necessarily result in homogeneous design , especially if more people can participate in defining that design. We can create participatory platforms through technology – like a game interface.

CLEANER: A game? I don’t have time to play games. My son, maybe. Sitting at home on his arse all day

OWNER: Think of it more like Lego.

CLEANER: A Lego… house?

OWNER: But for adults.

CLEANER: Look. If I’m going to spend the rest of my life working to pay off a mortgage, I want to know that that house is going to still be standing when I die, and that I can leave it to my kids. Even if all they do in it is sit around and play games. And for that, I want a building I can trust.

GLOW OF TECHNOLOGY

the students were still reflecting on the vision shared by the owner…

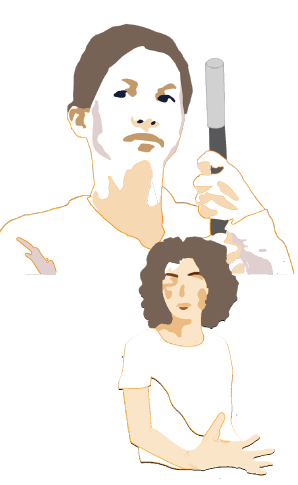

STUDENT 1: But automation is radically disrupting those old paradigms of construction. By incorporating compact, robotically-fabricated modules, we can simplify buildings from the many layers of wiring, insulation, bricks, studs etc that make the building process so complicated.

Automation will increase productivity by 60% in the construction sector, making building cheaper and putting design into the hands of the common man.

STUDENT 2: So robotics will actually allow us to make the built environment more human.

DRUNK GUY: Oh yes of course. The robots will make things more human.

STUDENT 1: Robotics in construction can also dignify the human experience, by reducing the need for people to do repetitive, physically arduous manual tasks and freeing their time for creativity.

CLEANER: Could you take your own glasses up to the bar when you’ve finished please

STUDENT 2: And that creativity can be manifested not least in everyone’s complete freedom to design their own built environment.

OWNER: Well, I wouldn’t exactly say that everyone should have complete freedom in designing the built environment. We have to leave room for expertise. Architects and designers have been trained for a reason.

THE BROOM & THE TOILET

To use the toilet, the bar had to ask their customers to use the one inside another bar across the street.

MANAGER: But let the line between expert and non-expert become more blurred.

DRUNK GUY: Where’s the toilet?

CLEANER: No toilet here love, you have to go to the bar across the street. They’ll let you use it if you download the app.

OWNER: Electricity, ventilation, and plumbing all come in the second roll-out. First priority is proving the case for timber housing, and then forest and plantation management to source the volumes of wood that will be needed.

MANAGER: I think a more realistic vision would be discreteness with a variety of materials.

OWNER: There’s a housing crisis. Wood is the only material that can be sustainably sourced at the volumes we need, and also sequester carbon in its form. And if it’s in modules, they can be disassembled and reused. It’s our best choice for housing material.

CLEANER: But whose decision is that to make?

WHO WE TALKED TO

TAKEAWAYS

Designers today are asked to look at a broader scope of problems, particularly regarding social and climate issues. The intention to be involved in these issues, as well as the effort to be relevant, is not to be criticized. The fact is, however, opinions can vary and there isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. Within our research question, we hoped to achieve a better understanding of democratisation in our built environment by interviewing individuals carrying different angles on the issue. Inspired by our interviewees, we created different roles to have a dialogue–a short play– as our medium to foster a conversation around this topic. Sometimes, a fictitious dialogue can introduce more transparency.

After interviewing professionals in the field and concluding our research, we wrapped up with some key takeaways which we hope could spark future discussions around the subject.

Technology

Technology can enable participation, but could also be a barrier

While most people in developed countries are becoming digitally literate, there is still a considerable amount of people who would be left out of the discussion. Considerably the elderly, minorities and people in developing countries would be the first to be excluded.

Technology is a tool

Technology is playing a pivotal role in driving change. New technologies can help us solve problems in ways that we never thought possible. However without policy, technology will tend to favor capitalistic interests and profit margins rather than creating an equal and fair world.

The role of the architect will need to change

If the building process did take this route, architects need to start assuming more computational roles. Designing systems rather than buildings and interlocking patterns rather than floorplans.

Democratisation

Democratisation can’t be top-down

Democratisation is not one person deciding what everyone else should do – and this includes specifying that “everyone can participate.

Individualism can’t reign supreme over societal cohesion

Democratisation isn’t everyone building their own idea of what a house should be, because a functional society requires some communal management.

Tools could facilitate participation – while retaining commonality

Embedding logic into the tools used by people who do want to design their own buildings could be a good balance – engaging participation, while retaining some degree of commonality.

Built Environment

Global problems need local solutions

It isn’t necessary to find one solution that fits all. Housing shortages, construction inefficiency and sector emissions are global problems, but can only be solved with solutions that acknowledge local parameters. Cultural differences, material availability, climatic differences, values resulting from socio economic differences can and should also be acknowledged in design tools.

Aesthetics means authorship

To be strongly associated with the built work by aesthetic or by style makes the creator, rather than the inhabitant, the main author of that space

Design the pattern; not the piece

Architecture doesn’t need to be formed from one unique part and it doesn’t have to be ten thousand. A middle ground could be achieved in order to allow for flexibility of materials and space.

What about the existing buildings?

We cannot keep building new, and must begin considering hybridization to design on top of the existing built environment.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

– Claypool, M. (2019, July). Discrete automation – architecture – e-flux. Discrete Automation. Retrieved June 13, 2022, from

https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/becoming-digital/248060/discrete-automation/

– Lynch, K., Banerjee, T., & Southworth, M. (1990). City sense and city design: Writings and projects of Kevin Lynch. MIT Press.

– Mamedova, S., Pawlowski, E., & American Institutes for Research. (2018, May). In the United States stats in brief – national center for education … Retrieved June 13, 2022, from

https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018161.pdf`

– Retsin, G. (2019, June). Toward discrete architecture: Automation takes command. UCL Discovery – UCL Discovery. Retrieved June 13, 2022, from

https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10117335/

– Sanchez Jose F. (2021). Architecture for the commons: Particpatory systems in the age of platforms. Routledge ; Taylor & Francis Group.

A Course Walks into a Bar is a project of IAAC, Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia developed at Masters in Robotics and Advanced Construction, in 2021/2022

by:

Students: Alfred Bowles, Grace Boyle, Yeo Jeong Kim

Faculty: Mathilde Marengo

Assistant faculty: Cecilia De Marinis