Abstract

Cape Town has recently had the most significant water crisis yet in its history. And although the crisis was averted, it has left Cape Town under immense pressure for the future to come with regards to water use and collection. Our project aims to collaborate in this effort by having 4 objectives in mind:

- Address Cape Town’s water shortage via water collection.

- Increase water-saving awareness via a visual landmark prominent in the city that people can relate to.

- Reuse as much material as possible in its construction, ideally discarded material.

- And rewild existing abandoned spaces in the city.

Day Zero

In 2018 Cape Town faced the most significant ecological challenge yet in its history, in what came to be known as Day Zero.

Day Zero is the day that the water taps will run dry. On the worst day of the crisis, day zero was as close as 30 days away. This prompted military action to preserve water usage among the population and enforce strict water measures. A person was only allowed to use 50 litres of water per day (instead of +800 average use per person in the US). This had massive implications for the economy and the people of Cape Town. It was considered a national disaster.

Even after the crisis was averted through enormous collective efforts, studies have shown that water-saving habits disappear after a period of abundance. Therefore, our project wants to aim to preserve the water-saving consciousness in the population and contribute as far as possible to water collection.

Water collection systems

Cape Town has a very peculiar weather pattern that is unique because of its location between the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean. Among the weather features we have is a persistent morning fog from Table Mountain into the city centre. Therefore, we decided to use a fog harvesting system as the primary water source for our project.

This system works via Raschel mesh erected on top of a substructure, so the fog goes through the mesh. As this happens, the water condensates into tiny particles collected at the bottom.

Our secondary water collection sources will be Atmospheric Water Generation through humidity and rainfall collection.

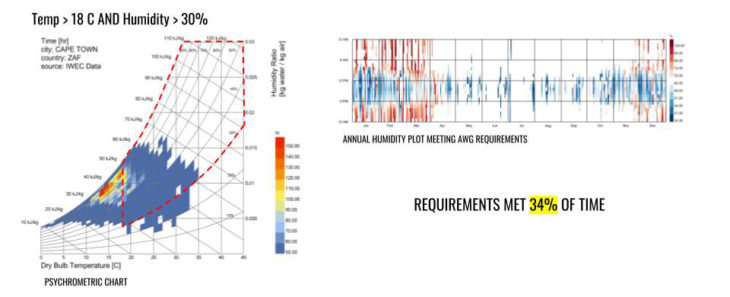

Humidity will be done via a system created by the ETH Zurich to collect water from humid conditions. As per our study below, these conditions are met in Cape Town 34% of the time.

Site selection

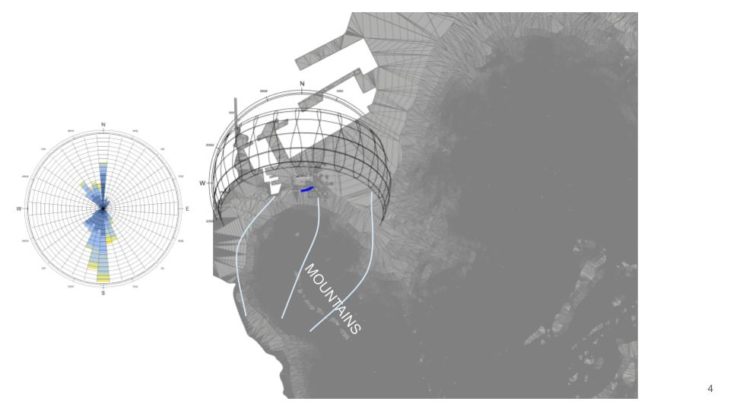

After conduction a wind study we observed that the fog comes down from the mountain into the city centre almost every morning.

The city centre was developed in the 60s, coming to a halt with the change of government in the late 80s. One of the abandoned projects is a project known as the Foreshore Highway. This highway was meant to work as an overpass. Incomplete and without use, the pieces of the highway are a landmark to an era that now is history in South Africa.

Because of this reason, we decided to use this incomplete highway as the place for our project. It is located near the city centre’s edge and receives plenty of fog from the mountain.

Create a landmark about water

One of our objectives is to create a landmark. Therefore we decided to build a tall structure close to or on the abandoned highway. After different interactions, we had two pieces: a Dome as a water collector sitting directly on top of the highway and a tower working as a fog collector.

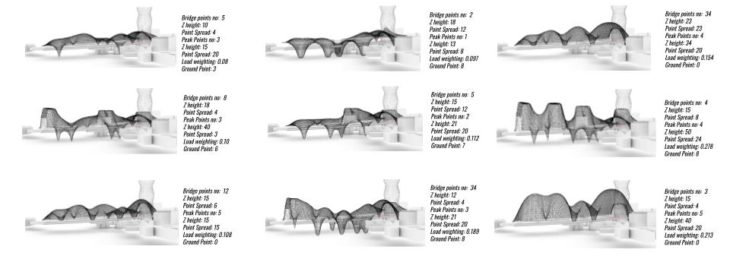

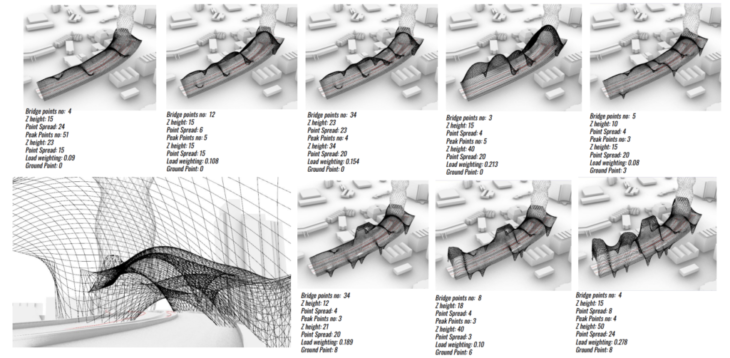

Developing this system further, we started to test various iterations for form-finding. To merge both the horizontal and vertical constraints, parameters were added to test various mass distributions. This primarily consisted of controlling connections between three key levels: ground, motorway and sky, while moving the density of points and mesh relaxation as constrained to the busy site conditions.

Next, The process then evolved to integrate internal circulation along the motorway and ground floor to work with the concept of creating this pilgrimage for water awareness. Finally, we realized that creating towers that connect directly through all three levels at fewer strategic points would enable better vertical accessibility across the site in combination with the horizontal route.

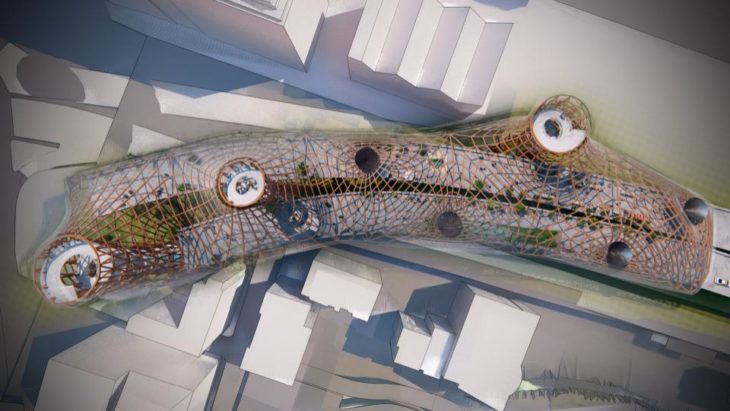

This then led to the selection of the following form, which took a more holistic shape from the entrance at the start of the abandoned motorway all the way to its unfinished peak with the tallest tower and primary lookout point. The lattice and membrane wrap from top to bottom, maximizing the surface area. The form is controlled by singular points arranged within a Voronoi distribution and then relaxed in kangaroo with positive or negative gravity forces.

Components

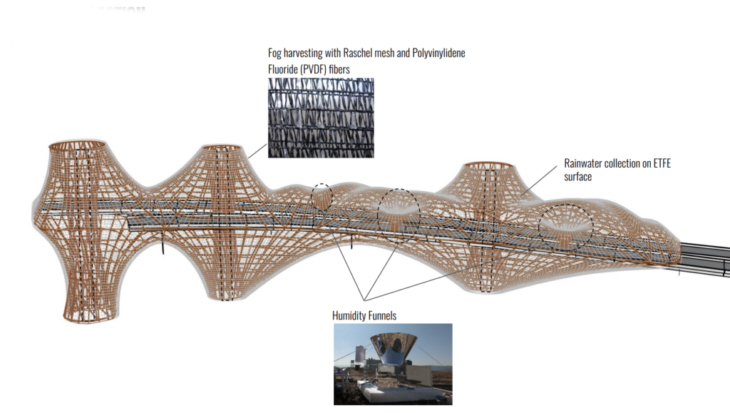

The basic outline of the scheme consists of 4 components. The motorway itself provides the primary route with 3 hourglass tower positioned to provide circulation to the top and intermediate floors. The primary lattice structure provides an ETFE skin to give shelter to the visitors within, while The final fog harvesting mesh is then applied to the outside surface.

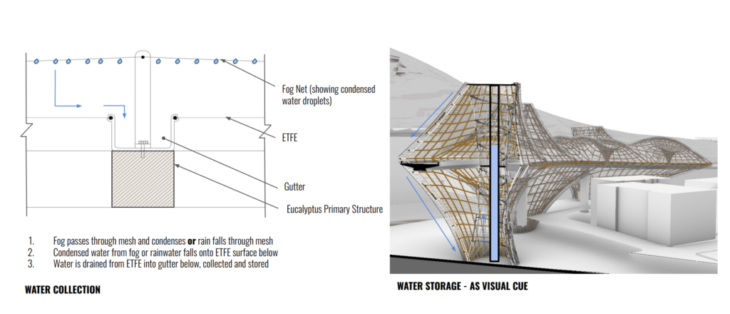

There are three main methods that we are using to capture water on our structure. The first method harvests fog with a Raschel mesh that has been specially designed with a triangular pattern combined with an oily PVDF coating to maximize water collection from passing fog. The second method uses metal funnels that were developed at ETH Zurich. These funnels self shade to collect water through humidity. Lastly, we plan to collect rainwater that falls on the structure’s surface.

We plan to detail our structure such that the ETFE support brackets also serve as a gutter that can collect and direct the water collected from the fog and rain. In addition, water will be stored in tubes at the centre of the towers that will serve as a visual cue to occupants of the state of the water crisis.

Materiality

Regarding the materiality, we looked into suitable woods available for creating free form wooden structures. Currently, in South Africa, vast amounts of non-native trees are very water-hungry and are responsible for using an equivalent of two to three months of Cape Town’s annual water consumption. In response, South Africa have been chopping down 10s of thousands of trees around local reservoirs to increase the water supply.

We decided to use the eucalyptus from these non-native trees that have been strategically removed due to their abundance, large lumber sizes, and good bending properties for free-form structures.

Structural Analysis

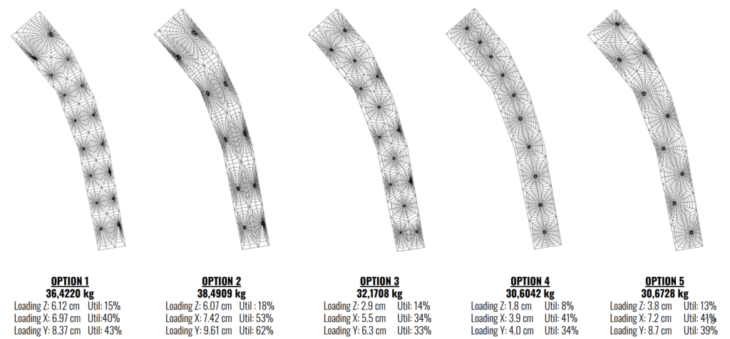

Once the shape was decided, we tested different iterations of the column positions to achieve the most efficient outcome. Out of the options outlined below, option 5 proved the most efficient.

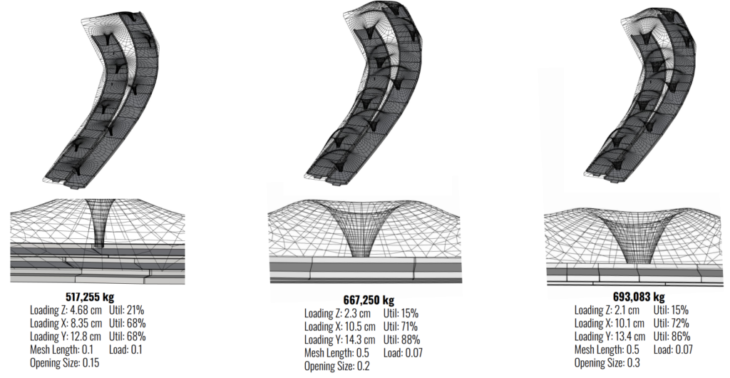

Regarding the column shape, we analyzed with Karamba 3 different options with varying diameters. The most efficient option was option 2, which balances mesh length and opening size.

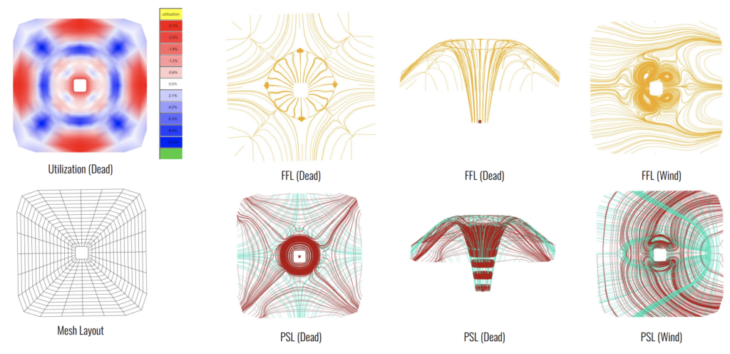

We then proceeded to test the lattice formation using pressure lines and force flow lines to choose the different lattice options that would form our structure.

We also tested different lattice iterations, settling on option 1 due to its simple shape and the easy assembly process.

Space program

The main objective of our project is to bring awareness to the water crisis while actively harvesting water from rain and humidity. At the same time, we want to reactivate an abandoned structure in the city.

People would access the Water Centre from the two ends: the right one on the same level, by car and the left one, ascending from the ground floor into the park through the ramp by foot.

This elevated park can act as a local open market and receive itinerant events for the local community. In addition, the space can be used for leisure, taking direct advantage of the water collected.

Access is also possible to the towers, so people can get different perspectives from the city while circulating around the water tubes, showing the level of water in the reservoirs.

The funnels that actively extract water from humidity can connect either to the pools and/or with the park reservoir.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, the best way to bring water awareness is by becoming part of the city’s daily life.

By having a structure that can create a space used every day while also full filling a water collection function using every possible aspect, from active to passive, we aim to create a greater consciousness of water’s value.

Credits

Cape Town Water Awareness Centre is a project of IAAC, Institute of Advanced Architecture of Catalonia developed at Master In Advanced Computation For Architecture & Design in 2021/2022 by students: Barbara Villanova, Sophie Moore, Michal Gryko and Bruno Martorelli and Faculty: Arthur Mamou-Mani, Fun Yuen, Krishna Bhat.