Converting Slums into Distributed Dwellings of Economic Growth

When Indian architect, Balkrishna V. Doshi, won the 2018 Pritzker Prize, the jury’s commemorative speech captured Doshi’s works’ philosophy in that “projects must go beyond the functional to connect with the human spirit through poetic and philosophical underpinnings”. This could be interpreted as nothing short of a battle cry for those in the design and build industry to join the small but growing league of professionals dedicating their careers to altering the social injustice of lack of dignified housing.

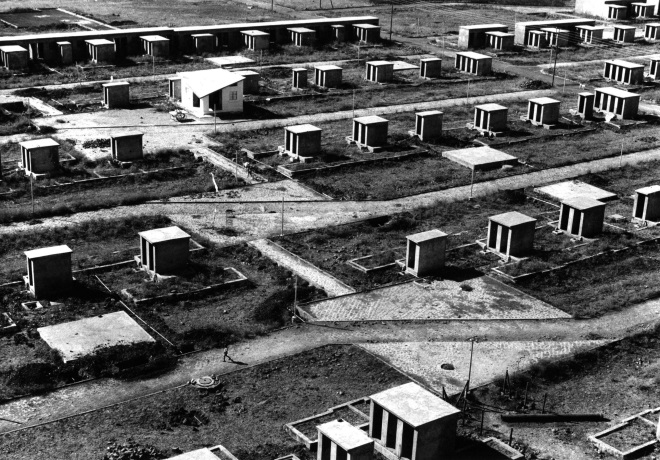

Schematic Street-Scape of Aranya Housing Scheme Source: BV Doshi

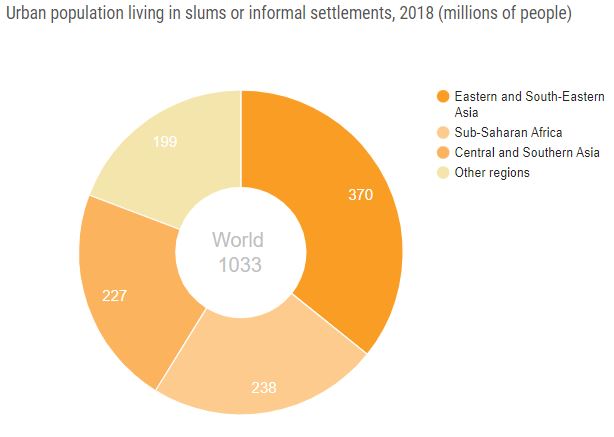

The global affordable housing gap is currently estimated at 330 million urban households and is forecast to grow by more than 30% to 440 million households, or 1.6 billion people, by 2025.Africa, projected to have the fastest urban growth rate, will by 2050 have its cities home to up to 950 million new inhabitants. To put the urgent need for sustainable, affordable housing in urban areas in context it would be necessary to note that today more than 23.5% of the world’s population is categorized as living in a slum.

Source: UNStats.UN.Org

The ‘ Converting Slums into Distributed Dwellings for Economic Growth’ study is hinged on the hypothesis that advanced architecture, well considered engineering and technology can solve the growing need for sustainable and affordable housing for (African) cities.

It was born out of three existential ‘Whys’ :

- ‘The African Slum’ is a narrative that has persisted even as the continent has strived to develop.

- We are currently in the 21st Century with the tools, technology and knowledge economy necessary to address these challenges and so why shouldn’t we?

- There’s a need to overhaul how to design and build social housing.

There ‘3 Whys’ evolved into 3 project mission statements :

- Place making – dignity , health, happiness, wellbeing

- Address living needs of people in an African context.

- Explore design in fractals as a vernacular design methodology within African homestead designs.

Chapters

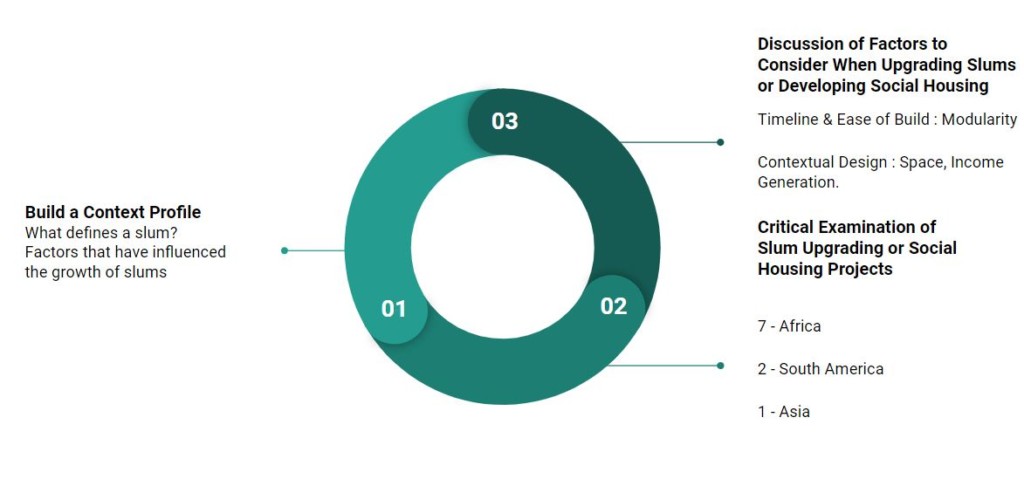

The study has been sectioned out into 4 chapters :

Methodology of Work Source: Author’s Own

Chapter 1 : Building a Context Profile

This chapter explores the factors influencing the emergence of a slum and what properties of informality convert a neighbourhood into a slum.

Chapter 2 : Critical Examination of Slum Upgrading Schemes and Programmes

A discussion of various methodologies used over the years in different countries in the name of slum upgrading and allocate a point score systems based on what design aspects have been tackled and how.

Chapter 3 : Discussion of Factors to Consider When Upgrading Slums or Developing Social Housing

This chapter will expound on the reality of realizing design aspects tackled in the second chapter.

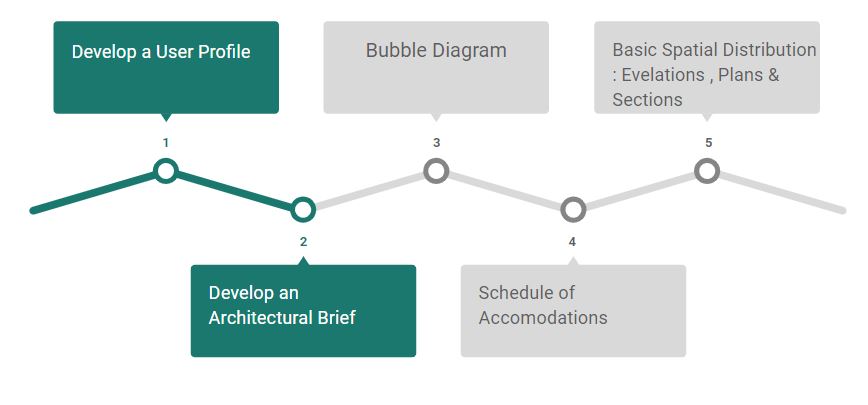

Intervention Proposal Source: Author’s Own

Chapter 4 : Design Intervention Proposal

Using a 5 step process this chapter will direct the design process from Developing a User Profile up to Basic Spatial Distribution with elevations , plans and sections.

So far four slum upgrading schemes have been analyzed and discussed as follows :

1. Aranya Community Housing – Indore, India

Architect : Balkrishna V. Doshi

Funded: Word Bank & India’s Housing & Urban Development Corporation

Source : Vastushilpa Foundation

Constructed in 1989 this scheme featured :

- 6500 brick houses – in sizes from a single room to larger homes for wealthier families.

- Plot sizes beginning at 35m2, with a simple plinth, a service core (a latrine and water tap or bath) and the option of a built room (the kitchen)

- Design around parks and courtyards, with groups of ten houses forming inward-looking clusters.

- Building around a central spine to accommodate businesses :shops, cafes and places to do business.

- A connection to water and electricity.

Source: Architectural Review ‘Revisit: Aranya low-cost housing, Indore, Balkrishna Doshi’, 2019

Plinth with sanitary infrastructure. Source: Vastushilpa Foundation

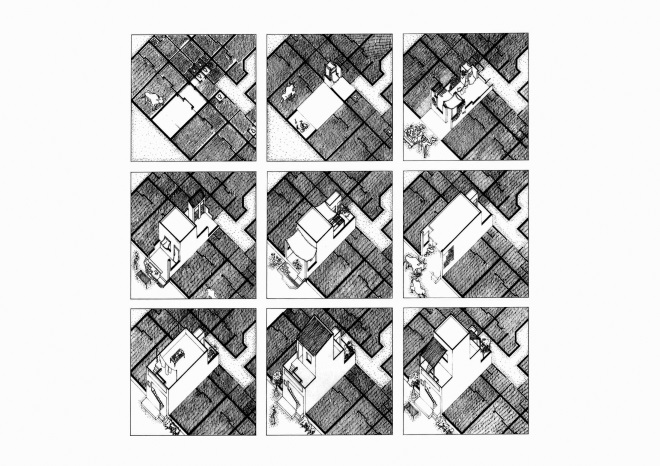

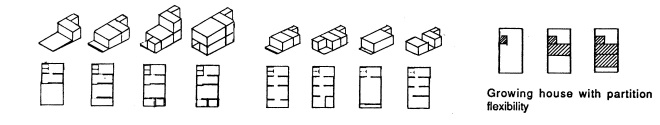

A prominent aspect of Doshi’s design was the freedom to reconfigure building plans based on the users needs and financial disposition.

Source: Vastushilpa Foundation

Source: Vastushilpa Foundation

2. Amui Djor – Accra, Ghana

Architect : Tony Asare

Funded: Norway, Sweden and the UK, Slum Dweller’s International UN Habitat

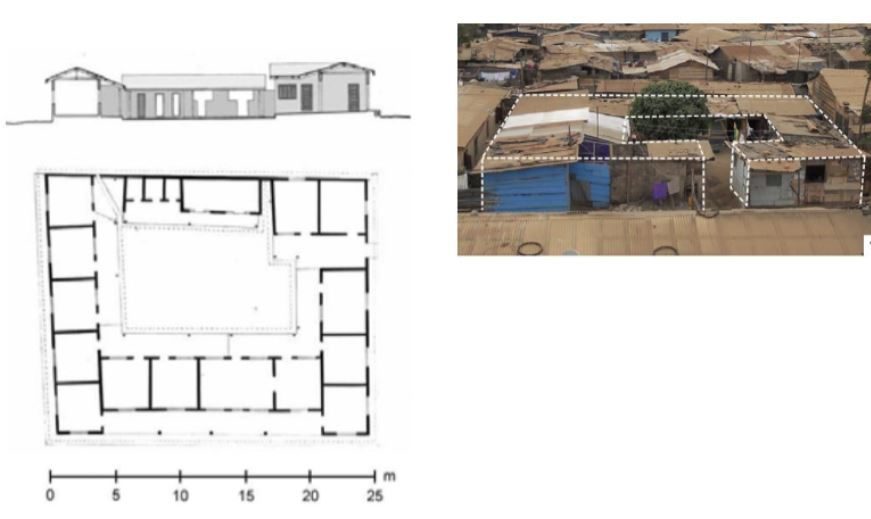

Amui Djior Community With Building Site Highlighted in Red. The image on the left shows original homes on plot. Source : Spatial Effects of Development Aid, Alexander Gogl

This development features:

- 90ft x 80ft plot size with 18 dwelling units and 6 commercial shops.

- 1 and 2 bedroom apartments.

- 32 families on the first and second floors, with the ground floor dedicated to commercial activities.

- Multiple-family units sharing a central court and other facilities. Shared spaces for cooking (both domestic and commercial), and a 12-seater public toilet and bathroom (managed by the cooperative), which subsidizes the cost of the housing. Visitors pay a small fee to use the services and the housing cooperative collects this money and uses it to help pay back its loans.

- A subsidy programme by the Energy Commission of Ghana by for rooftop solar photovoltaics.

- Vernacular architecture advising the distribution of spaces

Plan , section and elevation of original homestead existing in building footprint . Source : UN-HABITAT (2011) Ghana Housing Profile, Research Report & Spatial Effects of Development Aid, Alexander Gogl

Amui Djor Housing Project Source: Terry, A. (2013) Housing Project Brings Water, Sanitation to Amui Dzor Slum. Global News , African Union for Housing Finance Conference, Johannesburg, South Africa (2011). TAMSUF’s Role in Providing Affordable Housing in Ghana

The project was spearheaded by the Ghana Federation for the Urban Poor organising the residents into an association garnering them traction as they navigated the process of obtaining land tenure.

3. Mukuru Slum Upgrading Programme – Nairobi, Kenya

Funded: Nairobi Metropolitan Services, Misereor, the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations, SIDA, and Research Support from IDRC

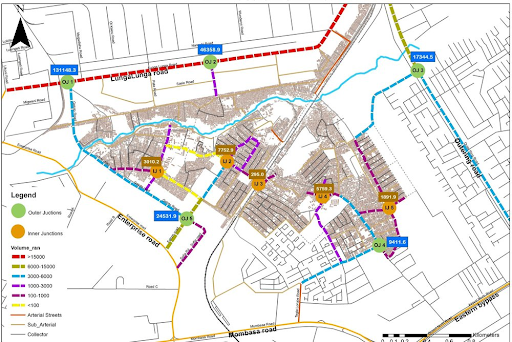

Mukuru Planning Map Source: SDI Kenya

Also propelled by the power of communal participation and ownership, this housing project has managed to secure land tenure for its residents through the declaration of the property as a Special Planning Area by the Nairobi County Government.

- 13,000 new houses on 60 acres, 400,00 residents

- Public infrastructure upgrades to water, waste and transportation.

- New health facilities

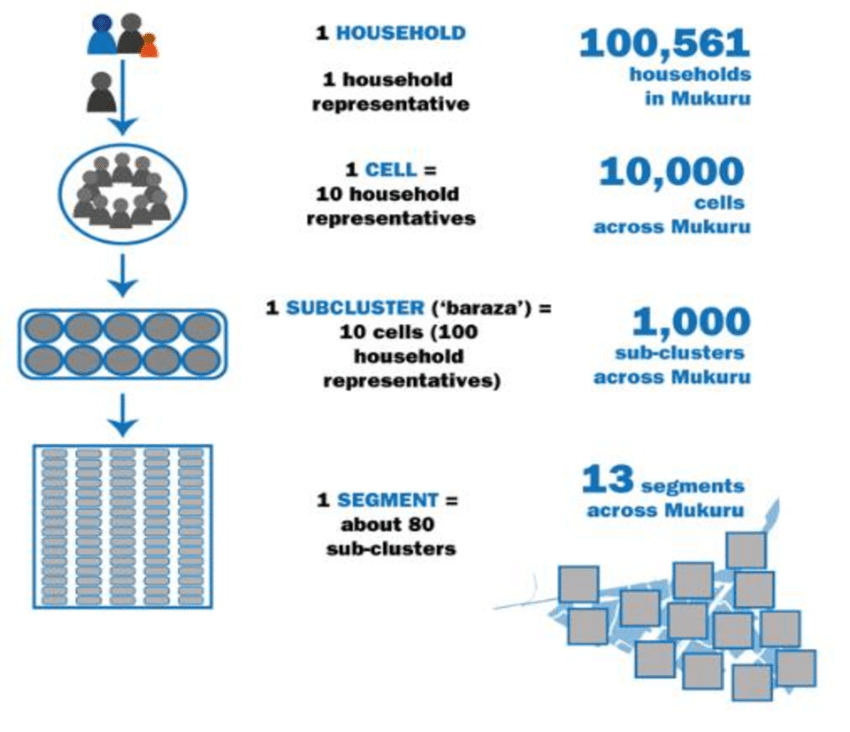

The 8 Mukuru SPA planning consortiums Source: Muungano wa Wanavijiji

Results of the Mukuru SPA community Mobilisation Process Source: ‘Scaling Participation in Informal Settlement Upgrading’ , Horn et al. 2020

4. Favela Barrios Programme – Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Architect: Luiz Paulo Conde

Funded: City of Rio de Janeiro

Colourful Painting of Walls as Part of Favela Barrios Programme Source: Getty Images

This programme was an exercise purely in infrastructural upgrading and policy reform that tackled the following aspects :

- Infrastructure interventions in water, waste and electricity.

- Upgrade to the postal delivery mechanisms in the barrios.

- Upgrades to public facilities in education, health and leisure.

- Public policy development that allowed for the availability of credit facilities to enable residents to renovate their homes.

- Introduction of a ‘pacifying’ police unit.

Urban Playground Source: Buenos Aires City Hall

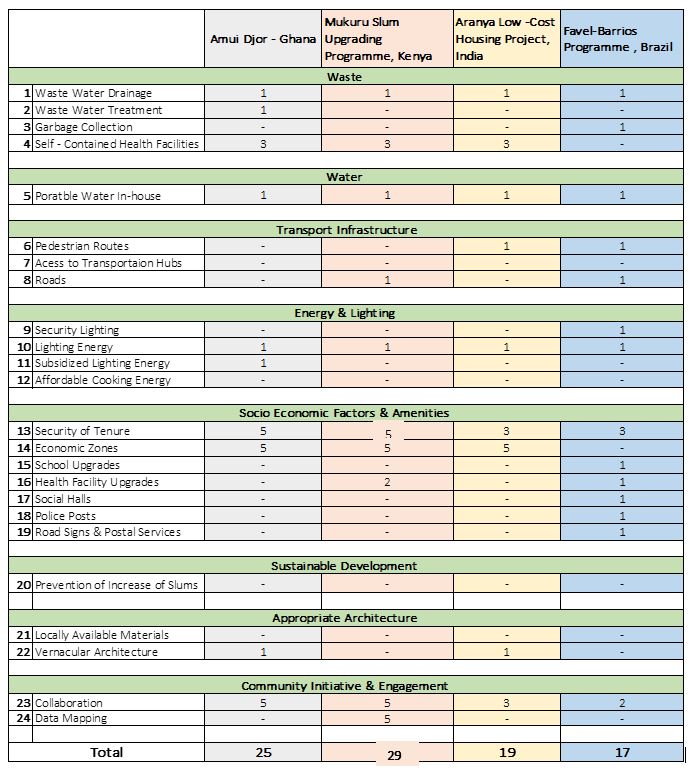

From examining the methods used by the different programmes, I built a preliminary rating scale incorporating interventions from allowing accessibility to portable water to community initiative and engagement. The scale rates against 24 factors ( o – 1) with those more crucial weighted heavier (0 – 5).

Rating Different Slum Programmes Source: Author’s own

Findings

The comparative methods in slum upgrading and social housing as shown above can be divided along the following duality of factors to anticipate success.

- Cooperative vs Individually Owned Homes

- Static vs Adaptable Design

- Sole Investment of public infrastructure vs Focusing on upgrading the homes as well

- ‘Modern’ Architecture vs Vernacular Architecture

- Community Mobilisation & Engagement vs Handout Approach

- Private vs Shared Sanitary Facilities

The lessons that this boils down to are that :

- Land Tenure is Everything : Governments need to come on board and recognise the need to relinquish these parcels of land to those most in need of them.

- Collaborative Design : Crucial in raising public interest , awareness and goodwill.

- Cooperatives or neighbourhood organisations play a big role in mobilisation.

- Need for Economic Zones : Slums are not solely housing neighbourhoods.

- No means to prevent growth of the slums post-improvement.

- Little attention paid to need for police or security.

- Social amenities such as hospitals, clinics, leisure facilities and schools are necessary and should be upgraded as well.

Intervention Proposal

This research project will move forward potentially as a white paper cataloguing and rating slum upgrading schemes and providing an intervention proposal for Gataka, an approximately 160 acre informal neighbourhood , 20 minutes from the central business district of Nairobi .

The initial questions to answer as I build a user profile would be on population density, demographics , average income and land ownership.

Slum upgrading is by all means a complex and multi-faceted issue to solve, here’s to hoping that I will be able to make a contribution, as small as it may be, towards tackling it.

” Converting Slums into Distributed Dwellings of Economic Growth” is a research paper of IAAC, Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia developed at Master in Advanced Ecological Buildings and Biocities in 2021/2022 by:

Student: Lillian Beauttah

Faculty: Kya Kerner