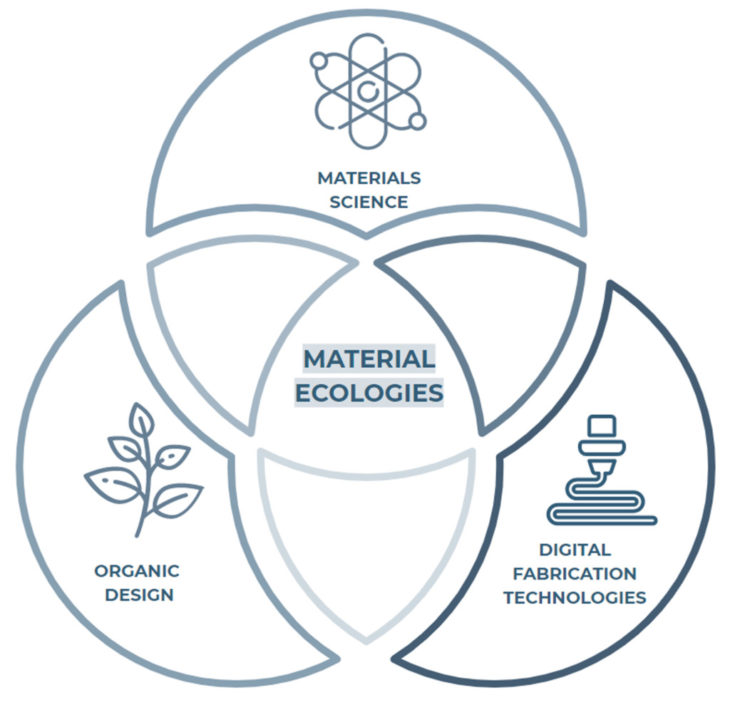

MATERIAL ECOLOGIES

Photo credits: oxman.com

INTRODUCTION

ECOLOGICAL THINKING / OBJECT-ORIENTED ONTOLOGY

The term Material Ecology describes a process of combining materials science, digital fabrication technologies, and organic design to produce techniques and objects informed by the structural, systemic, and aesthetic wisdom of nature.

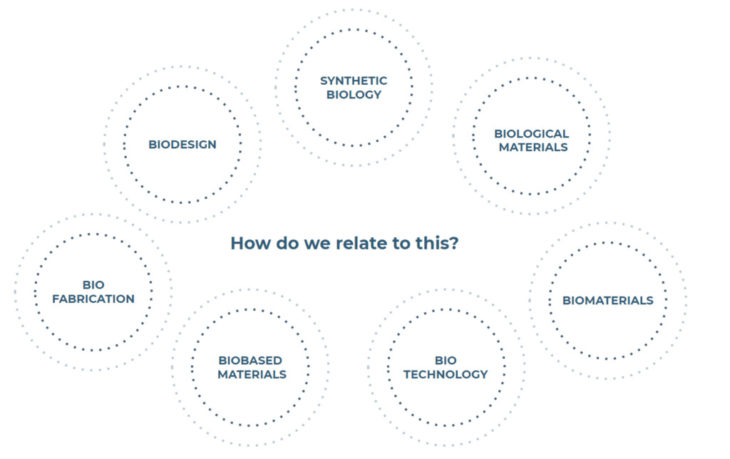

NEW TERMINOLOGIES

Finding their way into mainstream communication

simultaneously creates a set of buzz-word terminology, which may undermine or, even pass by, the urgency of developing such innovative methods and materials today. How do you relate to this?

LITERATURE REVIEW

ECOLOGY

‘Ecology is a troubled word that speaks of a troubled world’

Nikolic, 2018

Ecologies typically conform to two main ways of thinking nature

Typically, common understandings of nature fall into two tendencies – arcadian and imperial.

Arcadian nature is the order of ‘nature over there, the nature of ‘birds, bees and a pleasant view’, our aestheticization of nature’s forms holds it at a distance, is implicated in a sort of deterministic, teleological thinking regarding these forms rather than understanding, for example, creative evolution at the core of the complex mattering processes of nature. In this paradigm, the order of the ‘green nature, over there is a shallow, subject-centric distinction that objectifies and aestheticizes an ordered nature at a remove.

Considering, on the other side, Imperial nature as the order of nature that we frame, manage and engineer through instrumental reason, we land in the erroneous position of, as Bryant notes, the doubling of the system-environment distinction, wherein the system is always less complex than its environment, the system being precisely an ordered selection of an ever more complex outside that the system can never entirely account for. Furthermore, information on our environment typically comes from scientific fields that rarely converge – chemistry, physics, biology, increasingly bioinformatics and all of their respective subfields have differing accounts as to how matter matters, what it does, how, and even why. So in a sense, such ideas of an ordered nature managed by instrumental reason are deeply colonial.

How did these paradigms come to embed in our collective consciousness? And how to move past dualistic paradigms towards more lively relations, or, to recognize that lively relations were there all along so that we may respond appropriately?

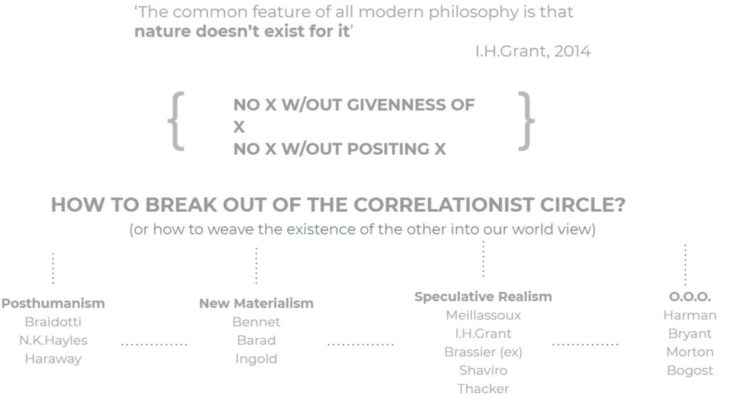

CRITICAL ECOLOGIES

A core thread running through new thinking on ecology seeks to find ways to move past Kant’s Copernican revolution, which Meillasoux summarises as No X without the givenness of X, No X w/out positing X.

This means:

- Firstly – that objects conform to mind, rather than mind to objects (where the mind does not merely reflect reality, but rather actively structures reality)

- Secondly – we can never know reality as it is in itself apart from us, what we know of anything is true only for us (a skepticism that concludes what doesn’t exist for the mind cannot exist at all)

Many OOO and speculative realist thinkers take issue with the fundamental idea underpinning modern, continental philosophy which is that of philosophy as access. The thinking subject assumes that his thought-derived system and maps are all-encompassing, that his demarcations grant him privileged access to the objects in his environment, he believes that his indications serve as shaping categories on the environment, not just on his own insular system. The epigenesis of pure reason, or the pathogenesis of concepts as Stella Sandford aptly puts it, established a system that interrogates only its own subject-object gap, which has far-reaching implications for fields outside philosophy.

Addressing this issue, speculative realists and OOO thinkers argue that indication does not precede distinction, there is no a priori, no virginal birth of reason that can transcend its own system-implicated conditions – its distinctions only pertain to the system doing the indicating and demarcating – not to the greater environment. A flattened ontology includes the human being with all objects that always recede from one another – there is no access, only information as perturbations of a system. Information in this sense is not an unchanging, eternal object, it is information only with regard to the disruptions of a system disturbed – difference that makes a difference.

I.H. Grant furthers this by pointing out that for systems predicated on ‘pure reason’, ungrounded construction is the norm. Unity is falsely ascribed when a distinction discovered is not explained through an account of its own position and system.

Y.Hui in his text DO also critiques a normalized relation between subject and object, questioning whether the subject can in fact create unity. He also points out the standard, erroneous conception of form as the ultimate source of production, and notes a technological tendency to separate form from matter. We can have such terms as ‘programmable’ or ‘active’ matter as we have already separated action and agency from matter. Matter in this way of thinking doesn’t matter, it is an inert resource waiting to be exhumed, extracted, and acted upon by human subjects thinking form first based on a groundless reason.

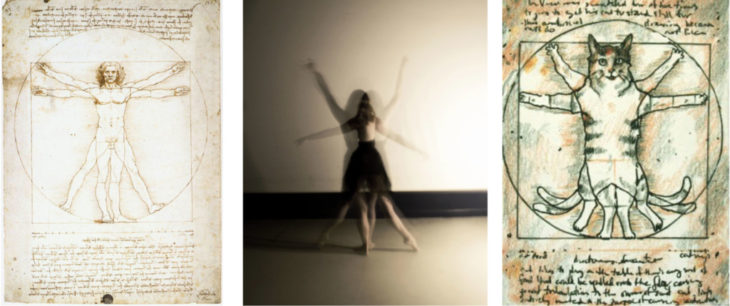

Vitruvian Man, Vitruvian Woman, Vitruvian Cat

But how reasonable is a reason with no grounds? As Achille Mbembe points out – we need to put reason on trial – the reason that has supported colonial invasions, eugenics, politics of exclusion, ecocide, and many other atrocities – reason needs to be more reasonable.

So, what is a reasonable stance with regard to environments fundamentally different from that of our insular systems, and what does it mean to consider that matter matters beyond pleasant forms and fantasies of the engineered control of life? How can we understand and relate to the mattering of matter and what are the implications of shifting our view of matter’s agency?

One of the key arguments put forward by posthumanists, new materialists, and speculative realists alike is a decentering of the so-called exceptional species, the human-becoming, placing him on a plateau with non-human others typically relegated to the nature ‘over there’. Such arguments often propose a more sustainable notion of vitalist, self-organizing materiality and subjectivity as an assemblage that includes non-human agents.

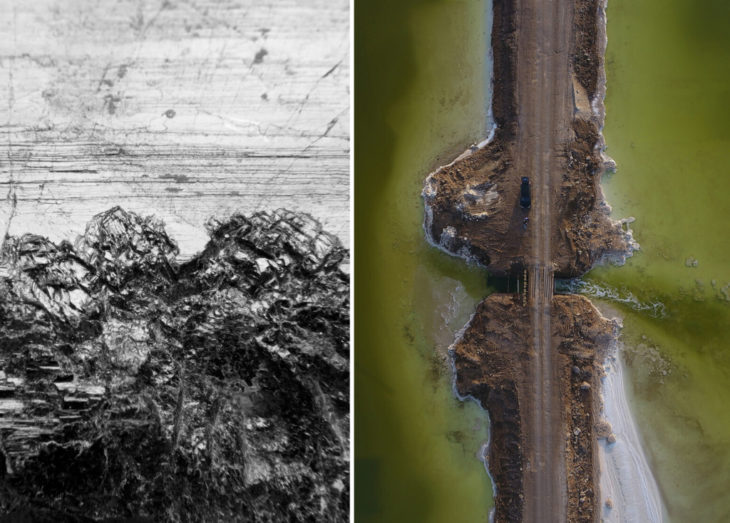

(right)Yiannis Hadjiaslanis, Formless Formation, 2020, digital photograph. (left)Liu Chuang, Lithium Lake and the Lonely Island of Polyphony (detail), 2020. Three-channel video, color, sound, 35:55 minutes. © and courtesy of the artist and Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

As Ben Woodard clarifies in his text on the German Idealist Schelling, “Nature is not some local part of the universe, wild and untouched, but the processes that constitute the productive, stabilizing and diversifying attributes of existence”. How can we stop relating to the earth and what we would typically refer to as ‘matter’ as the object to our subject – operating at a remove, drawing upon a reason with no grounds, consequence, or limit?

As Meillasoux states in After Finitude, the materialism that chooses to follow the speculative path is thereby constrained to believe that it is possible to think a given reality by abstracting from the fact that we are thinking it. (AF, 36). So, how to think our way out of thought?

How can or should we use our unique human capacity for thought to think better? How to be more reasonable in the face of materialities both digital, biological and the shades in between that transfigure and transform us, and so, what then is mind, or reason in these contexts?

“..the cosmology of a given age is not the result of a unilinear, ‘scientific’ development, but rather the most striking, imaginative symbol of its mentality — the projection of its conflict, prejudices, and specific ways of double-think onto the graceful sky’

P106 Koestler, The Sleepwalkers

(Right)Illustration of a Sonrel, Leon (1872) Bottom of the Sea, New York City, NY: Scribner, Armstrong & Co. Image: Public Domain/Freshwater and Marine Image Bank, University of Washington. (Left)Arjuna Neuman and Denise Ferreira da Silva, Blacklight, 4Waters-Deep Implicancy, 2018 (left). The Otolith Group, Zone ll, 2020 (right).

As Timothy Morton outlines, we should use our capacity for sensitivity to reason with all of our senses, including their technological prostheses. Placing ourselves within a plane of all matter, things and beings alike brings with it an immensely vast perspective and with it intimacy and strangeness. Ecological thinking entails that we become very sensitive, open, and receptive and that we maintain resilience in negotiating these strange relationships. Bogost articulates such a reframing of the task of philosophy as one of ‘amplifying the black noise of objects to make the resonant frequency of the stuff inside hum, to write speculative fictions of their processes, their unit operations, their alien phenomenology’. As Bennett clarifies, ‘the new charm of things is rooted in their being seen as things, which begins when they are no longer objects for subjects’.

Reason’s striving for abstraction and formal perfection denies us the richness, multiplicity, plenitude, and particularity of things – the woods, chaos, and matter of the real world.’ (Spec. p14) On this point, N.K. Hayles argues that we should use our capacity for the imagination to better understand the environments we participate in and which shape us. When challenged with the imperative of radical change, we can perhaps rely on instinctual responses as tangents through which to imagine new worlds we cannot possibly, reasonably ‘know’. As Shaviro reminds us ‘beauty is a lure, drawing me out of myself and teasing me out of thought. The aesthetic subject does not impose its form upon an otherwise chaotic outside world. Rather this subject is itself informed by the world outside, a world that fills the being before the mind can think’ (Shaviro in SPeculations, p11).

Ecological thinking asks that we invest in imagination, an imagination that is grounded in transformative processes that unsettle and disrupt even as they evoke the seemingly sublime – that seeks to understand creative evolution, not just its end products.

CASE STUDIES

We will now look at a set of case studies exploring the idiosyncrasies of material ecologies in practice.

CASE STUDY 1

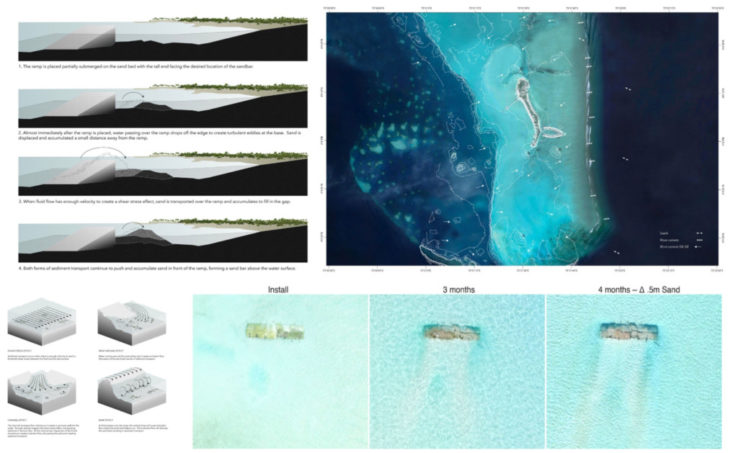

Growing Islands

Skylar Tibbits – Self-Assembly Lab

Maldives

Photo credits: Self-Assembly Lab

Creating a system of underwater structures that use wave energy to promote sand accumulation in strategic locations. Over time, the goal is that the self-organization of sand will grow into new islands or help rebuild coastlines, creating an adaptable solution to protect coastal communities from rising sea levels.

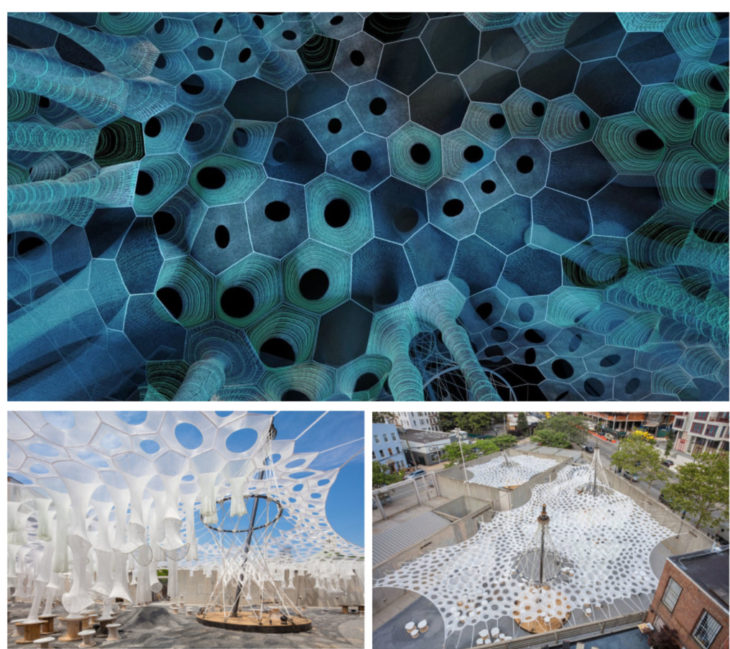

CASE STUDY 2

Lumen

Jenny Sabin Studio

New York

Photo credits: Jenny Sabin Studio

Lumen is an immersive, interactive installation at MOMA PS1 courtyard, a socially and environmentally responsive structure that adapts to the densities of bodies, heat, and sunlight.

Lumen applies insights and theories from biology, materials science, mathematics, and engineering. Material responses to sunlight as well as physical participation are integral parts of our exploratory approach to new materials, embodiment, and transformative, adaptive architecture. The project is mathematically generated through form-finding simulations informed by the sun, site, materials, program, and the structural morphology of knitted cellular components. Resisting a biomimetic approach, Lumen employs an analogic design process where complex material behavior and processes are integrated with personal engagement and diverse programs. Through direct references to the flexibility and sensitivity of the human body, Lumen integrates adaptive materials and architecture where code, pattern, human interaction, environment, geometry, and matter operate together as a conceptual design space. Knitting and textile fabrication offer a fruitful material ground for exploring these nonstandard fibrous potentials. As with cell networks, materials find their own form where the flow of tension forces through both geometry and matter serves as active design parameters. Lumen undertakes rigorous interdisciplinary experimentation to produce a multisensory environment that is full of delight, inspiring collective levity, play, and interaction as the structure and materials transform throughout the day and night.

CASE STUDY 3

Jammed Bio-Welding

David Benjamin -The Living

Photo credits: Domus

Bricks of live mycelium and corn fiber grow on each together within formwork investigating the compression of the biomaterials to form a solid or a semisolid structure that is capable of healing itself.

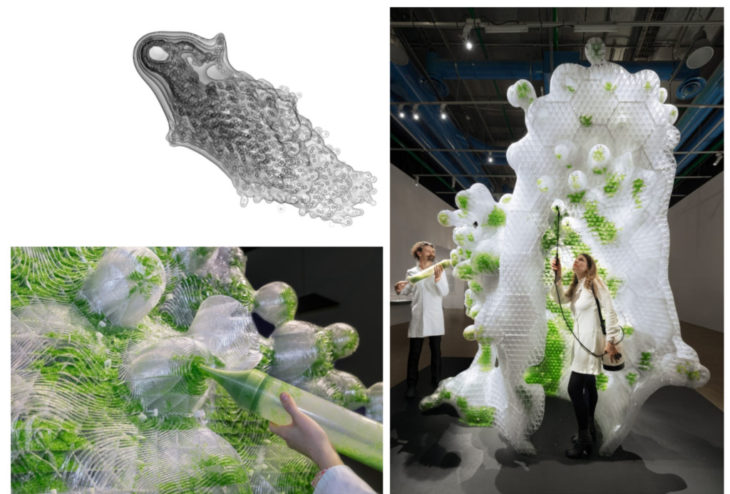

CASE STUDY 4

H.O.R.T.U.S. XL Astaxanthin.g

Claudia Pasquero & Marco Poletto – ecoLogicStudio

Photo credits: ecoLogicStudio

H.O.R.T.U.S. XL Astaxanthin.g is a large-scale, high-resolution 3D printed bio-sculpture receptive to both human and non-human life.

In H.O.R.T.U.S. XL Astaxanthin.g, a digital algorithm simulates the growth of a substratum inspired by coral morphology. This is physically deposited by 3D printing machines in layers of 400 microns, supported by triangular units of 46 mm, and divided into hexagonal blocks of 18.5 cm. Photosynthetic cyanobacteria are inoculated on a bio gel medium into the individual triangular cells, or bio-pixel, forming the units of biological intelligence of the system. Their metabolisms, powered by photosynthesis, convert radiation into actual oxygen and biomass. The density value of each bio-pixel is digitally computed in order to optimally arrange the photosynthetic organisms along iso-surfaces of increased incoming radiation. Among the oldest organisms on Earth, cyanobacteria’s unique biological intelligence is gathered as part of a new form of biodigital architecture.

In the digital era, a new interaction is emerging between creativity and the fields of life science, neuroscience, and synthetic biology. The notion of “living” takes on a new form of artificiality. This project confronts the dictates of human rationality with the effects of proximity to bio-artificial intelligence. It is developed in “collaboration” with living organisms. Their non-human agency is mediated by spatial substructures we have developed while studying biological models of endosymbiosis.

CASE STUDY 5

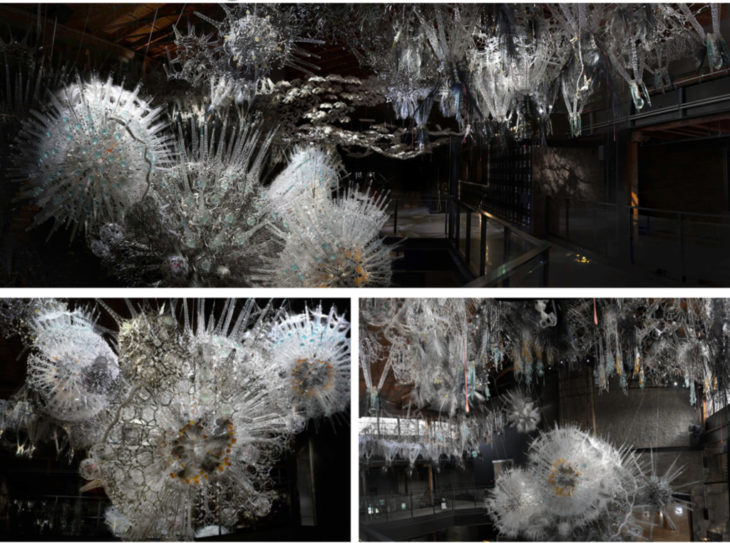

MEANDER , Philip Beesley

Tapestry Hall

Cambridge, Canada – 2020

Photo credits: Philip Beesley Studio

Meander is a large-scale immersive testbed environment constructed within a historic warehouse building at the center of residential high-rise development in Cambridge, Ontario. The meshwork scaffolds which comprise the testbed are organized as a series of species within an artificial ecosystem, gently flexing and responding to the movement of viewers.

Similar to natural environments such as rivers and clouds, large groups of parts pass physical impulses and data signals back and forth, enabling the entire environment to work as an interconnected whole. The innovations in Meander suggest ways of making adaptive, sensitive buildings of the future.

CASE STUDY 6

Silk Pavilion I+II

Neri Oxman

MOMA Exhibition\ Silk Pavilion I+II, 2018, Over the course of her 20-year career

“Material is not considered a subordinate attribute of form, but rather its progenitor.”

Oxman N.

Photo credits: oxman.com

The work of Neri Oxman, founder of the Mediated Matter Group at the MIT Media Lab, takes integration to an extraordinary level. The silk Pavilion shows how humans collaborate with other species to create new materials and structures without depleting natural resources? The innovations enable a new age of ‘biological alchemy’ whereby micro-organisms can be designed to mimic ‘factories’ and materials strategically augmented at their basic biological properties.

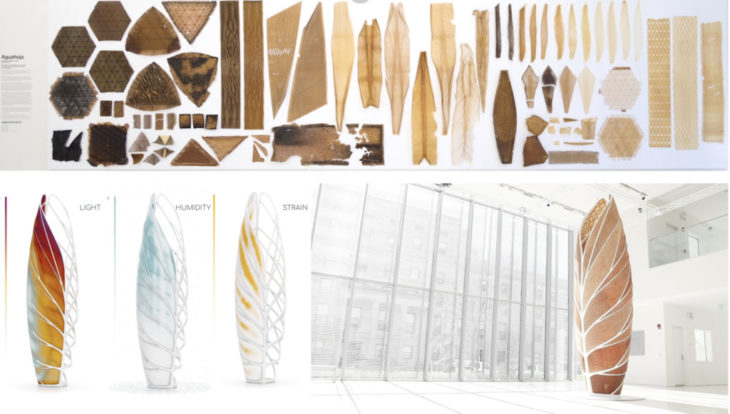

CASE STUDY 7

AGUAHOJA II

Neri Oxman /MIT Media Lab

MOMA Exhibition 2014-2020

Photo credits: oxman.com

Derived from the sea and returned to the soil, it is the utilization of decay as a design feature. This project envisions the ability to temporarily divert materials from healthy ecosystems, integrate them in human designs, and enable natural decomposition back into the environment for purposes of fueling new growth. It brings the built environment closer to the natural and biological environment.

CASE STUDY 8

BIODESIGN/ Bioreceptive Concrete, 2018

Marcos Cruz /UCL

Bio-Integrated Design

Bioreceptive design: A novel approach to bio-digital materiality. Concrete can be made more bio-receptive, and have developed facade panels specially designed to encourage the growth of cryptogams – organisms such as moss, algae, and lichens – which require no irrigation.

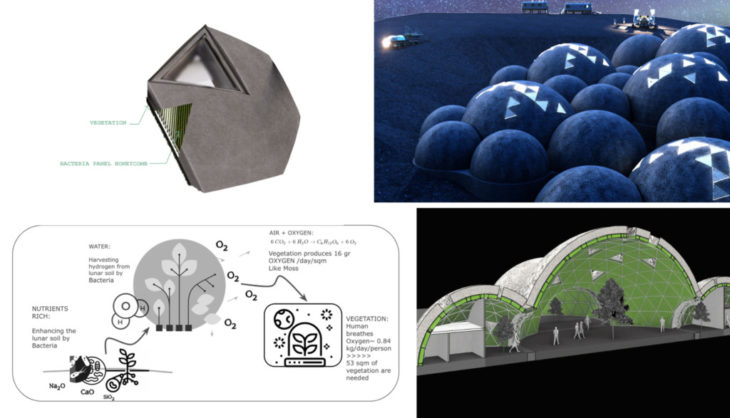

CASE STUDY 9

Seleno[Bio]Habitat

ABED E. BADRAN, JONATHAN HERNANDEZ, ALEKSANDRA JASTRZ?BSKA, IAAC

Seleno[Bio]Habitat is an experiment of the practical concept of growth with time, capable of producing viable community dwellings as biospecies at any given moment of growth”. It might evolve in the future and create successive descendant habitats that variant from the ancestors.

CASE STUDY 10

Resurrecting the Sublime

Dr. Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg

(left)Dried specimen of Hibiscadelphus wilderianus Rock, collected by Gerrit P. Wilder on Maui Island, Hawaii in 1910. Courtesy Gray Herbarium of Harvard University. (Middle) Digital reconstruction of the extinct Hibiscadelphus wilderianus Rock on the southern slopes of Mount Haleakal?, Maui, Hawaii, around the time of its last sighting in 1912. (Right)Hibiscadelphus wilderianus Rock (vitrine with smell diffusion, lava boulders, animation, ambient soundscape).

This work by artist Dr. Daisy Alexandra Ginsberg is the culmination of an interdisciplinary research project spanning scent, synthetic biology, and artistic practice. Core questions that motivate Ginsberg’s research are erudite and apparently simple, with complex implications and no easy answer – What does it mean to design life? Can you design it? How might you design it well?

Resurrecting the sublime similarly began from an ostensibly modest point, asking ‘Could we ever again smell flowers driven to extinction by humans?’ This question motivated an ongoing collaboration between artist Dr. Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, smell researcher and artist Sissel Tolaas, and an interdisciplinary team of researchers and engineers from the biotechnology company Ginkgo Bioworks. Using tiny amounts of DNA extracted from specimens of flowers stored at Harvard University’s Herbaria, the Ginkgo team used synthetic biology to predict and resynthesize gene sequences that might encode for fragrance-producing enzymes. Using Ginkgo’s findings, Sissel Tolaas used her expertise to reconstruct the flowers’ scent in her lab, using identical or comparative smell molecules.

The work explores the re-purposing of synthetic biological knowledge to show the possibilities sometimes overlooked by scientists and engineers, thereby demonstrating the potential for novel, creative directions for research. As Sissel Tolaas notes, the artist can ‘dare to be less practical’ meaning their creative agency grants them freedom for experimentation, which also gives a certain unique angle and space for critique.

By bringing extinct species back to life within the context of a public exhibition, with a predominately aesthetic drive, the work implicitly questions the underlying idea of hubris in terms of human intentions to control life, where we should examine how, if at all, we acknowledge the limits of prediction and control in science and engineering. There is a need to explore ‘technologies of humility, in order ‘to come to grips with the ragged fringes of human understanding – the unknown, the uncertain, the ambiguous, and the uncontrollable’ (p. 227)

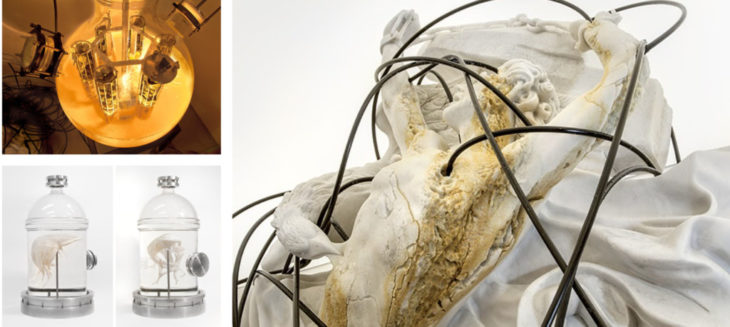

CASE STUDY 11

Prometheus Delivered

Thomas Feuerstein

(Top Left) KASBEK (detail), 2017 glass, steel, pyrite, chemolithoautotrophic bacteria (Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans), plastic tubes, measurement and control technology, 260 x 100 x 75 cm. (Bottom Left) OCTOPLASMA, 2017 glass, human liver cells (hepatocytes) with fibroblasts, formalin, aluminum, plastic, 70 x 43 cm. (Right) PROMETHEUS DELIVERED, 2017 marble, plastic tubes, stainless steel tub, euro pallet, scissor lift table, 280 x 145 x 85 cm

exhibition view PROMETHEUS DELIVERED, Haus am Lützowplatz, Berlin 2017

This work by Austrian artist Thomas Feuerstein is the result of years of research and collaboration with teams from the Department of Microbiology and the Department of Radiotherapy and Radiooncology at the University of Innsbruck. Core questions that motivate Feuerstein’s work are – How do digitalization and biotechnologies change the relations of life and power, the production and distribution of goods and resources under capitalism, our relationship to the biosphere, and ultimately our self-understanding as individuals? Are concepts such as individual, subject, and author still tenable in today’s world?

The marble sculpture forming the centerpiece of Prometheus Delivered is a replica of Prometheus Bound by Nicolas Sébastien Adam (1762) which links biological systems, the technoscientific, and the grammar of mythology, to comment on materially bound relations and their implications.

Central to the work is the myth of Prometheus, who had to make right the idiocy of his brother Epimetheus who gave all the powers to the animals and forgot to leave any for humans, forcing Prometheus to defy the gods and gift fire (often associated w/ techne) to the naked and defenseless human-being, for which he was punished – chained to a cliff face, his liver endlessly devoured, endlessly regenerating in a cruel cycle. The myth links creative mastery and a striving for autonomy in an embodied purgatory.

In Feuerstein’s work, the sculpture of Prometheus is slowly decomposed or devoured by chemolithoautotrophic bacteria (rock-eating bacteria).

The acidic process water from the bioreactor (at left) flows into the body of the sculpture via tubes and runs off the surface of the stone. The limestone turns into gypsum while the sculpture slowly dissolves. The biomass of the bacteria is then the energy source for the growth of human liver cells – fed to a system generating the organic sculpture octoplasma (bottom, second from left) grown by colonizing a three-dimensional matrix of human liver cells (hepatocytes) and fibroblasts in vitro in a bioreactor. This work is preserved in formalin and consists of both human liver and octopus cells.

The system as a whole transforms a mechanistic idea of metabolism by turning inorganic stone into organic meat. Feuerstein’s exploration of ‘metabolic humanities’ considers the processes of breaking down and transforming matter – the creative and generative flowing with the devouring of form only to reconfigure it again, transformed and hybridized. Feuerstein’s metabolic machines are characterized by constant exchange and plasticity, obscuring a distinction between organism and inanimate matter. Feuerstein says of his work: ‘I see bacteria and somatic cells as sculptural actors, biochemically relating a molecular story of evolution and becoming human. The associated metaphors and mythologies, while linguistically quite different, consider the same story from a human perspective. In this respect, meanings and processes converge in the question of form, which is actualized as transformation’

The work prompts us to notice that at the core as humans we are material metabolic beings, part of flux and more porous to environments than our ideas of hermetically sealed systems may allow.

As Hannah Landecker explains in ‘A Short History of Metabolism’ – previously the ultimate aim of biochemists was to give a complete account of the transformation undergone by matter in passing through organisms’ however, today metabolism means something like the inverse – the transformations undergone by organisms as they pass through matter.’ Metabolism draws us into our environment and the environment into us such that they are inextricably linked, showing that intimacy and proximity can be both exquisitely horrific and disturbingly beautiful.

REFLECTION

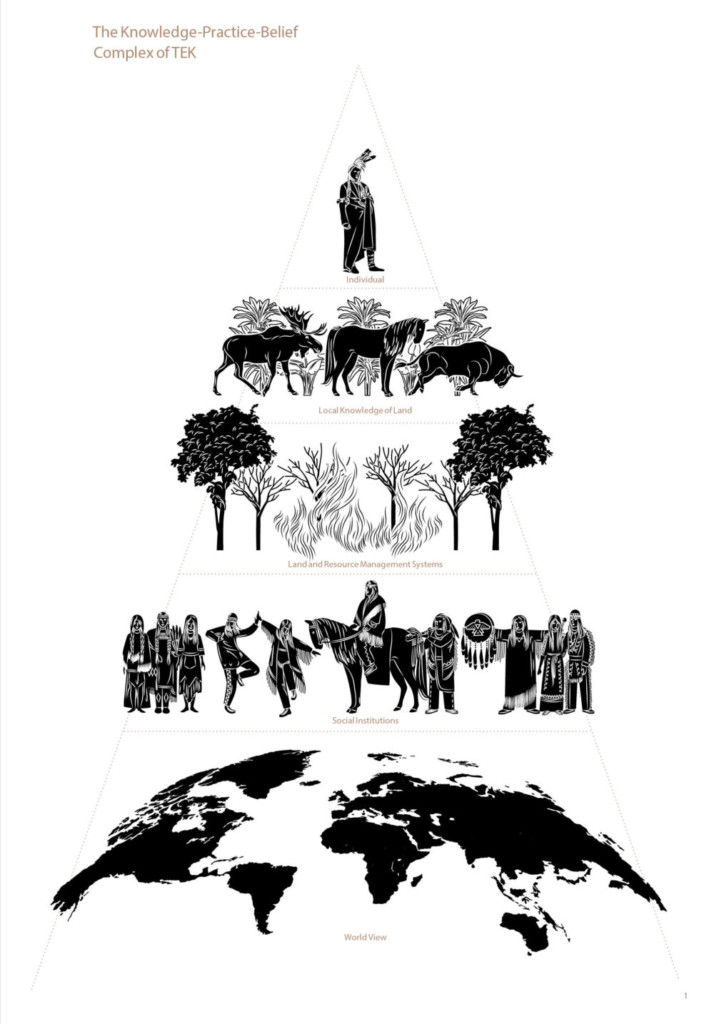

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK)

A cumulative body of multigenerational knowledge, practices, and beliefs. Forming the foundation of indigenous technologies is TEK.

This model, coined by ecologist Fikret Berkes, translates the complexity of Traditional Ecological knowledge into a western scientific framework.

Photo Credits: Julia Watson

The first and foundational level is the local knowledge of animals, plants, soils, and landscapes. The second level involves resource management, composed of local environmental knowledge, practices, tools, and techniques; and involves an understanding of ecological processes and performances. The third level involves community and social organization, offering coordination, cooperation, and governance. The fourth and final level is that of worldview, which involves religion, ethics, and general belief systems. A worldview provides guidance to interpret our observations of the world around us. Each aspect of this Complex is important in maintaining a symbiosis between humans and nature.

REFERENCES

Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter a political ecology of things. Duke University Press.

Calvert, J., & Schyfter, P. (2017). What can science and technology studies learn from art and design? Reflections on “Synthetic Aesthetics.” Social Studies of Science, 47(2), 195–215. doi.org/10.1177/0306312716678488

Chapter 2 Post-Anthropocentrism: Life beyond the Species. (n.d.). [online] Available at:paas.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/braidotti_posthuman.pdf [Accessed 21 Dec. 2021].

Grant, I.H. (2014). Speculations on Anonymous Materials [Online] Available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=cMoTh3HpO0E

IAAC Blog. (n.d.). Seleno-Bio-Habitat-Integrative-Modeling. [online] Available at: www.iaacblog.com/programs/seleno-bio-habitat-integrative-modeling/ [Accessed 21 Dec. 2021]

lateraloffice.com. (n.d.). WATER ECONOMIES 2009-10 – LATERAL OFFICE. [online] Available at:lateraloffice.com/WATER-ECONOMIES-2009-10 [Accessed 21 Dec. 2021].

Inc, P.B.A. (n.d.). Philip Beesley Architect Inc. | Sculptures & Projects. [online] www.philip beesley studio inc.com. Available at: www.philipbeesleystudioinc.com/sculptures/Meander/index.php [Accessed 11 Nov. 2021].

Jenny Sabin Studio. (n.d.). Lumen. [online] Available at: www.jennysabin.com/lumen

Nikolic, M. (2018). Ecology (minoritarian) [Online] Available atnewmaterialism.eu/almanac/e/ecology-minoritarian.html

Meillassoux, Q. (2008). After finitude?: an essay on the necessity of contingency . Continuum.

Neri Oxman (2013). Towards a Material Ecology – MIT Media Lab. [online] MIT Media Lab. Available at: www.media.mit.edu/publications/towards-a-material-ecology/.

Nineteen68, L. (2012). vitruvian-woman_pe. [online] Flickr. Available at: www.flickr.com/photos/doyoubleedlikeme/8164616833/in/pool-824622@N21/ [Accessed 21 Dec. 2021].

Self-Assembly Lab. (n.d.). Growing Islands. [online] Available at:selfassemblylab.mit.edu/growingislands

Stiefvater, M. (2007). Vitruvian Cat. [online] Flickr. Available at: www.flickr.com/photos/maggiestiefvater/478894161 [Accessed 21 Dec. 2021].

Watson, J. and Taschen Gmbh (2019). Lo–TEK : Design by Radical Indigenism. Köln: Taschen.

www.daisyginsberg.com. (n.d.). ALEXANDRA DAISY GINSBERG. [online] Available at: www.daisyginsberg.com/work/resurrecting-the-sublime [Accessed 21 Dec. 2021].

www.thomasfeuerstein.net. (n.d.). Thomas Feuerstein: WORKS / PROMETHEUS. [online] Available at: www.thomasfeuerstein.net/50_WORKS/07_PROMETHEUS [Accessed 21 Dec. 2021].

MATERIAL ECOLOGIES is a project of IAAC, Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia developed in the Master In Advanced Computation For Architecture & Design 2021/2022 by students: Abed E. Badran, Jumana Hamdani, Lucie Ketelsen, and Faculty: Jane Burry