The Green Dip

Covering the city with a jungle

The Why Factory workshop at IAAC / MaCT

Winy Maas (Professor)

Javier Arpa (Coordinator)

Adrien Ravon (Teacher)

Lex te Loo (Teacher Assistant)

February 1st 2018 – February 11th 2018

The Why Factory, The Willow House, 2013

Why Green?

Covering our buildings with green stuff is hip. It looks good. It seems to contribute to a green agenda. It suggests helping cooling the city and to store water. It says to increase the biodiversity of the city. But some see it as a misleading and commercial enterprise that doesn’t help our cities. Some say it is highly unsustainable as winds will blow them away, and it is vulnerable due to uncertain maintenance. What is true here? In this study, we want to explore the pros and cons of this controversy.

40 cities will be selected to show how we can cover roofs, terraces, balconies and even walls and facades with plants. A study that will be based on a selection of building types, such as a residential tower, a soccer stadium and a theatre/museum.

For each of these types the following questions will be answered:

- What species can grow?

- How much soil do they need?

- How much water do they need and how much can they store?

- How much evaporation and cooling do they provide with?

- How much maintenance do they need?

- What are the effect of sun and wind orientation?

- What is the impact of height?

- What do they contribute to the biodiversity of the city?

- How much does planting cost?

And importantly: how will these buildings look like? And in the end, how will the city look like? The result of these studies will be an atlas of potentials. Finally, we will calculate the outcome of covering built matter with this new nature:

- How much the temperature in the city can drop?

- How much oxygen can be produced?

- How much CO2 can be captured and stored?

- How much water can be stored?

- How many birds can be offered life and habitat?

Part 1 – The Green Planet

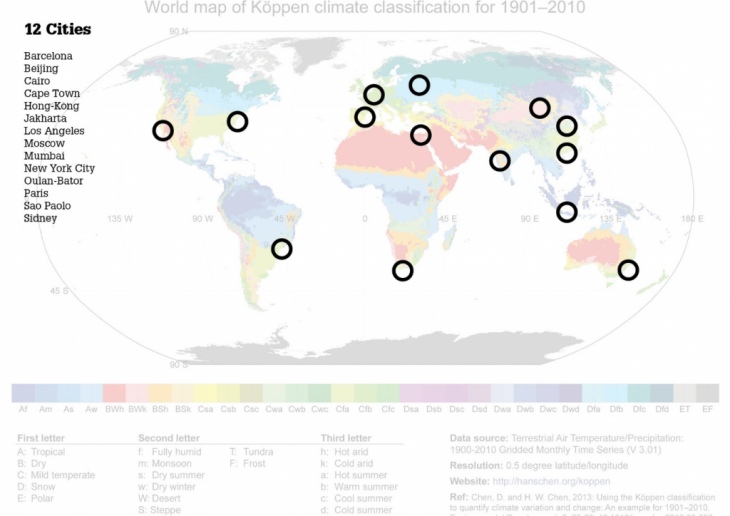

Cities selection based on Koppen climate classification

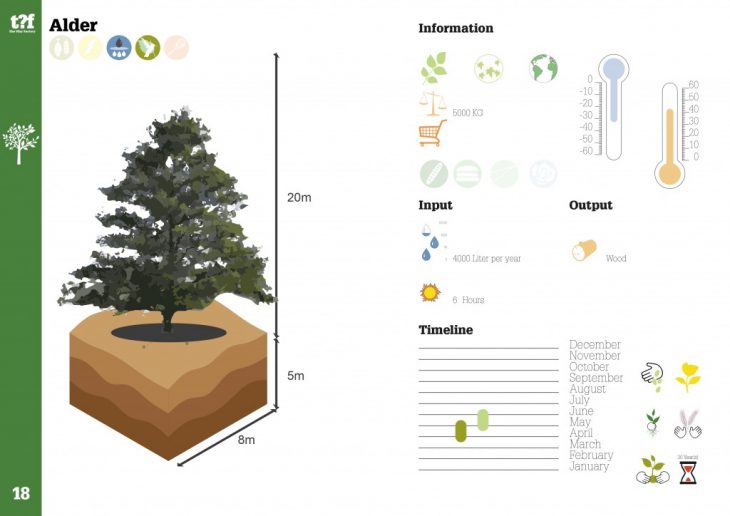

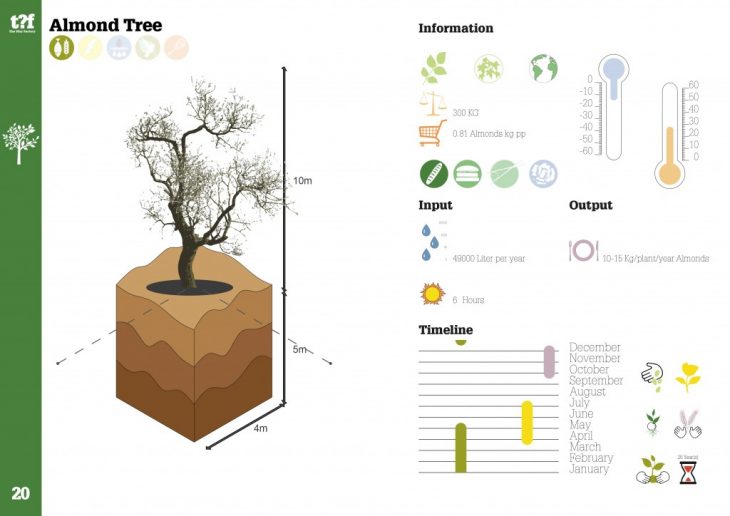

In order to critically look at greening solutions for cities, we want to approach the greening controversy by looking at the planet as a whole. Indeed, the different climates provide with some specific environmental conditions for native species to grow. For this part of the workshop, we have selected 14 cities, covering a vast array of world climates. We will look at the density, climatic conditions and more specifically, at the native flora in those regions. In order to give an overview of those different climates, we will propose a common template for comparison. Students will produce a catalogue of the representative native flora. For each species, students will gather data about their needs (dimensions, volume of soil needed, weight, water consumption, daylight hours, season, maintenance, estimation on investment and running costs) and environmental benefits (air pollution removal, air temperature reduction, ultraviolet radiation reduction, carbon storage, pollen, building energy conservation, wind reduction, stream flow reduction, evaporation, water storage, estimation on financial profits).

Please see here for reference

https://www.ebben.nl/en/treeebb/

This first exercise will lead to the development of a collective database. It will be the starting point for testing and evaluating different greening solutions on different urban forms.

The Why Factory, 3d Nature, 2013

The Why Factory, 3d Nature, 2013

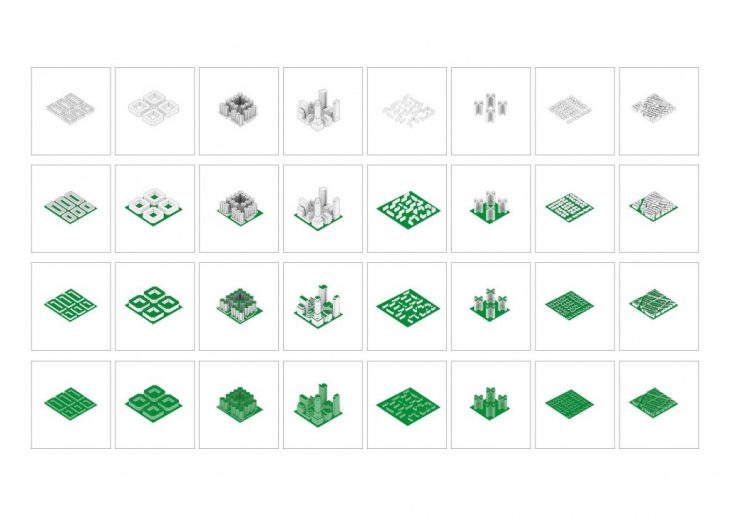

Part 2 – Green Buildings

The Why Factory, 2019

What are the existing and future solutions for implementing vegetation in buildings? During this part, we will look at rooftops, facades, balconies, and the ground levels, as potential solutions. What is the impact of planting a specific species on those building parts? This exercise will systematically explore the implementation of precise species on different urban forms. We’ll explore a collection of different urban forms. From blocks, towers, slabs, courtyards, urban villas, row houses, street, public space, we develop tools and methods to evaluate this impact.

This part of the workshop will be supported by a series of calculations aiming to measure the impact of covering cities with green in different climates. It aims to develop a method to calculate the environmental benefits and estimates the costs of ‘greening’ our cities. This exercise will be supported by a series of tools. Students will be introduced to Grasshopper and Rhinoceros 3D in order to develop a comparative model and catalogue of solutions.

Grasshopper 3d can be downloaded here:

https://www.grasshopper3d.com/page/download-1

Part 3 – Green Cities

Green Beirut, Studio Invisible, 2011

Visions are not just mere collages. They require precision, critical and visionary thinking. They are a tool to illustrate the impact of different scenarios. In his text ‘Why be Visionay’ published in 2009 in Visionary Cities, Prof. Winy Maas defines the term as “part curiosity, part exploration, part fantasy, and part real problem solving”. The full text is attached in appendix. During the last part of the workshop, students will produce a series of Photoshop images exploring the greenification of 14 cities with different species. Each student will produce five beautiful images, testing the implementation of five different species on a specific city. This will lead to a collection of 70 beautiful images. Some support will be provided in order to introduce some specific Photoshop technics. At the Why Factory, research and education are blended. Therefore, the studio or workshop is a place for the development of a collective research. Students work at the same time individually and collectively. Some collective template are provided in order to facilitate the collective and comparable production. Besides, some ‘experts’ will named depending on the skills, curiosity, focus and interest of everyone. Ecological services expert, database expert, Photoshop expert, Grasshopper 3d expert, template and presentation expert, economic expert, etc…

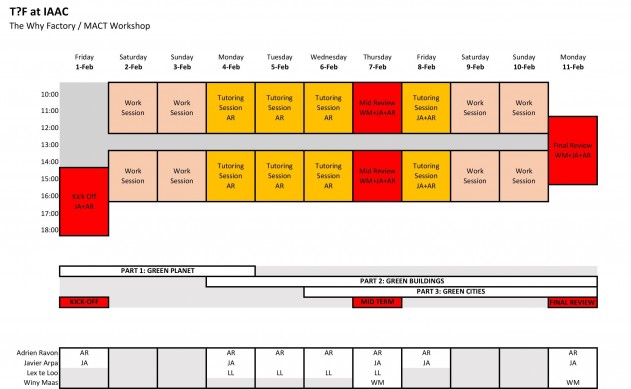

Schedule

Day 1: Kick Off Session (JA+AR)

Friday 1st of February

15:00 – 19:00

Day 2: Work Session

Saturday 2nd of February

10:00 – 18:00

Day 3: Work Session

Sunday 3rd of February

10:00 – 18:00

Day 4: Progress Review (JA+AR+LL)

Monday 4th of February

10:00 – 13:00 & 14:00 – 17:00

Day 5: Table Crit (AR+LL)

Tuesday 5th of February

10:00 – 13:00 & 14:00 – 17:00

Day 6: Progress Review (AR+LL)

Wednesday 6th of February

10:00 – 13:00 & 14:00 – 17:00

Day 7: Mid Review (WM+JA+AR+LL)

Thursday 7th of February

10:00 – 13:00 & 14:00 – 17:00

Day 8: Table Crit (JA+AR)

Friday 8th of February

10:00 – 13:00 & 14:00 – 17:00

Day 9: Work Session

Saturday 9th of February

10:00 – 18:00

Day 10: Work Session

Sunday 10th of February

10:00 – 18:00

Day 11: Final Review (WM+JA+AR)

Monday 11th of February

10:00 – 15:00

Faculty

Winy Maas is an architect and urban designer and one of the co-founding directors of the globally operating architecture and urban planning firm MVRDV, based in Rotterdam, Netherlands, known for projects such as the Expo 2000 pavilion, the vision for greater Paris, Grand Paris Plus Petit, the Market Hall in Rotterdam, the Crystal Houses in Amsterdam and the Seoullo7017 Skygarden in Seoul. He is furthermore professor at and director of The Why Factory, a research institute for the future city, he founded in 2008 at TU Delft. He has been Visiting Professor at GSAPP Columbia and IIT Chicago and has held teaching positions at various universities and institutes worldwide. With both MVRDV and The Why Factory, he has published a series of research projects.

Javier Arpa is the Research and Education Coordinator of The Why Factory. He also holds a position of lecturer in the Landscape Architecture Department of the University of Pennsylvania. Javier has taught at Harvard, Columbia and Pennsylvania Universities in the USA, ENSA-Bellevile and ENSA-Versailles in France, and IE University in Spain. He is the curator of the exhibitions Paris Habitat and Paysages Habite?s, both held in 2015 at the Pavillon de l’Arsenal in Paris, and is the author of the monograph Paris Habitat: One Hundred Years of City, One Hundred Years of Life. In 2013, he co-organized the conference The City That Never Was in cooperation with the Architectural League of New York. As lecturer and researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, he is currently conducting the research project Africa: An Atlas of Speculative Urbanization. Javier was Editor in Chief for a+t research group, one of Europe’s leading publishers in architecture and urban design. He worked for a number of architecture firms in Argentina, The Netherlands, Spain, and France, and led several urban planning projects in China.

Adrien Ravon is an architect, teacher, and researcher whose work combines a theoretical and technical approach. Ravon completed his studies at the FADU-UBA, Buenos Aires and at the ENSAPM, Paris, where he defended his Master’s thesis in January 2011. After collaborating as an architect with Officina Urbana in Buenos Aires and Jakob+MacFarlane in Paris, Ravon was appointed teacher and researcher at the TU Delft, where he joined The Why Factory. Since September 2011, Ravon has worked on various research and education projects that focus on urban futures, tools and design methodologies. He had a key role in advancing the Future Models course, which provides specific computing support to The Why Factory’s work. He co-authored The Why Factory’s publications Barba (nai010 publishers, 2015), Copy Paste (nai010 publishers, 2017) and PoroCity (nai010 publishers, 2018). In the frame of his collaboration with The Why Factory, he has worked with various institutions worldwide. At the TU Delft, he has supervised The Why Factory’s graduation unit for the past three years. In parallel, Ravon worked as a consultant at MVRDV in 2017 and 2018.

Hardware / Software requirements

The workshop will use Rhinoceros, Grasshopper, Photoshop and InDesign.

Students are required to bring their own laptops.

Grasshopper can be downloaded here:

https://www.grasshopper3d.com/page/download-1

Assignment

The workshop will be organized around three parts:

- Part 1: Green Planet (Data collection)

- Part 2: Green Buildings (Rhino+Grasshopper+Calculation)

- Part 3: Green Cities (Photoshop)

Deliverables

- A catalogue of 14 cities including information about density and climate

- A catalogue of 70 species including their different ecological benefits and needs

- A catalogue of axonometric drawings and calculation based on the implementation of different species in specific urban forms

- A series of beautiful Photoshop images (70 in total)

Students are requested to submit all the material on the IAAC Gdrive and a Blog post need to be curated on iaacblog.net for each project (see “IAAC | Publication Guidelines”) within a maximum of 1 week after the end of the Seminar.

Grading System

- 0 – 4.9 Fail (submission of a supplementary work by May)

- 0 -6.9 Pass

- 0 – 8.9 Good

- 0 – 10 Excellent/Distinction

On this basis, students will be evaluated on several aspects such as:

- Attendance – 15 %

- Participation – 20%

- Results 45 %

- Presentations 20 %

Contact

For questions, please contact:

adrien@thewhyfactory.com

javier@thewhyfactory.com

The Why Factory

The Why Factory (T?F) is a global think-tank and research institute, run by MVRDV and Delft University of Technology and led by professor Winy Maas. It explores possibilities for the development of our cities by focusing on the production of models and visualizations for cities of the future.

Education and research of The Why Factory are combined in a research lab and platform that aims to analyze, theorize and construct future cities. The Why Factory investigates within the given world and produces future scenarios beyond it; from universal to specific and global to local. It proposes, constructs and envisions hypothetical societies and cities; from science to fiction and vice versa. The Why Factory thus acts as a future world scenario making machinery.

We want to engage in a public debate on architecture and urbanism. The Why Factory’s findings are therefore communicated to a broad public in a variety of ways, including exhibitions, publications, workshops, and panel discussions.

The work of The Why Factory has been exhibited at various events, such as the Business of Design Week, 2009, Hong Kong; Foodprint Manifestation, 2009, Den Haag; Imaginarium, 2010, Berlin; and Vertical Village, which has been shown in the Museum of Tomorrow, Taipei, 2011, at The Total Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul, 2012 and Hamburg Museum, Hamburg, 2013, COAM Madrid, Madrid, 2016, Munich Architecture Gallery, Munich, 2017, Dutch Design Week, Eindhoven, 2017, Centre Pompidou, Paris 2018, Manifesta Biennale, Marseille 2018.

At the core of The Why Factory’s campaign is a series of books —the ‘Future Cities Series’—, which is being published in association with nai010 publishers in Rotterdam. In the ‘Future Cities Series’ the following books have been published: Visionary Cities (2009), Green Dream (2010), The Why Factor(y) (2010), The Vertical Village (2011), Hong Kong Fantasies (2011), City Shock (2012), World Wonders (2014) and Barba (2015), Absolute Leisure (2016), Copy Paste (2017), PoroCity (2018). Upcoming publications are, 4 Minute City, Hong Kong Towers, BiodiverCity and Wego.

Why be visionary?

What is a vision? Winy Maas gives his view on the need for and potential of visionary thinking in architecture and urbanism. This text has first been published in the Why Factory’s first publication Visionary Cities in 2009.

What is a vision?

A vision is, in a way, what happens between a question mark and a proposal. It asks the big questions and then paints an image for the future with its answer. Most importantly, it is a dream for the city and for its spatial translation that offers a long-term, cohesive, seductive, and strong perspective for future societies. It is part curiosity, part exploration, part fantasy, and part real problem-solving. The role of the visionary is to guide and direct and summarize the course for this increasingly urban world.

Why do we need one?

As you see in the urgencies outlined in this book, it is time to begin thinking about our cities in a completely new way. The urban environment is fundamentally different than it ever has been before, but we are still trying to physically define it in the same way. We don’t know how to move forward because we are caught in a splintered reality. We see a strange contradiction. On the one hand cities and communities are highly individualistic and enormously based on the individual unit, and on the other hand global awareness has come to life more than ever before.

We are seeing, like never before, that people are able to survive in almost self-contained cities. The pure individualism afforded by relatively new technologies such as television and the Internet have challenged the necessity of the city as a place for exchange and for access to particular experiences. You can live anywhere, you can work anywhere – every farm in Switzerland with a bit of technology can house the world’s best workers and activities that in the past were limited to the classical city. Some people say that the city does not even exist anymore.

At the same time, we are also seeing that the planet is collectively being conceived for the first time in history as ‘a ball’ – as one entity, one continuous place. Because people can travel farther and more often; because the population is mixed and has been cross mingled and is not connected anymore with a country; because the monitoring of the planet has become more apparent and because a crisis is almost always global.

Diseases like this H1N1 Virus, or the financial crisis, or the climate crisis are everywhere – they are no longer just local. Every point on the globe is much closer for everybody than it ever was before. The spaces between the classical cities are used for urban agriculture, industries, housing and leisure. The Mont Blanc is busier than Trafalgar Square. Whatever we do in a city – whatever city – has an effect on that city’s exchange with other cities, and has a wider effect than ever before. In this way, one might argue that the city is everywhere; that the world has become one big city.

To me, these two extremities describe the need, from both ends, to bring them together into possible constructions, and those constructions are probably describing the word vision.

So why don’t we make one then?

Unfortunately, this need for vision comes at a time when we are reluctant to even use that word – vision. There are some people who say that they have a vision, and if it’s Al Gore and his perspective on the environment, or if there are a certain kind of religious leaders that have a particular vision of how the world should be because of their beliefs, we are skeptical of their visions because, in the worst case, they can be too extreme, too holistic, too narrow-minded or too exclusive. If at times we are anxious about visions because they are small, we are equally afraid of visions because they are big. They are (again in the worst case), top-down, bureaucratic, politically motivated projects that take too long, cost too much, and never fail to provide us with reasons to criticize them. The faults of these large-scale efforts feed our skepticism towards the collective and towards governments and bigger planning as well.

Instead we have developed a different kind of planning. A bottom-up, agent-oriented planning where small special interest groups are represented by agents who advocate their demands. It has become the time of the NGOs. In the same way that we are able to sustain ourselves in our private cities, catering only to our own needs, we expect city planning to do the same. A new level of economic, cultural, societal richness has led to a certain kind of protectionism. We are happy with what we have and we want to hold onto it. We are also in a position where we are entitled to protest and to resist more than before. As a result, more and more plans take much more time to realize. It they even are realized. In Switzerland the average realization time for a building has risen to eight years. In the Netherlands highway realizations can take more than 20 years, the extension of the A4 for example. These developments paralyze the evolution and growth of the city. They frustrate, if not kill classical urbanism.

Another part of it has to do with the loss of differentiation. With more and more global markets for architects, with the greater communication and sharing of image production, one can see much more similarity, much more copy-paste architecture, less classical uniqueness between architects. In recent architectural biennials it is clear to see that everyone’s work is very similar to everyone else’s, that the uniqueness of the architect is disappearing.

At the same time there is now a tremendous pressure on architects to make the unexpected, by clients, by developers, by politicians, who seek, for economical and electoral reasons, ‘difference’. We are expected to be fantasy makers, and even beyond that to make something that is beyond all the fantasies that have come before and this intimidates many of us. Actually, architects are quite behind in their imagination of the future. It is a huge risk to look forward into the unknown territory of tomorrow. The fear of taking ownership of an idea so big and so unknown has become much more predominant because of the conditions I have described. In the time when we most need a visionary, it is in many ways the most difficult time to be one.

How do we do it?

First, let’s uncover a collective ambition, a wider goal. We need to ask ourselves if there are bigger issues that affect our individual lives, and if so, how we are going to tackle them, on our own, or with a bigger group? Thus the collective appears immediately; urbanism is there. And what we can notate now is that the collective space may seem completely different, but it has always been there. It is there by the desire of people to organize traffic, or to organize safety or to organize food products or organize medicine. There is a huge tendency, even reflected in the market, that describes a huge collective desire. The intriguing thing now is how that kind of desire effects individualism, and how it affects our cities, and if that will lead to other kinds of cities, and if that will lead to other kinds of organizations, and so on.

It becomes visionary again, when you can begin to paint, in a spatial manner, what the world will be like or should be like in order to improve that balance between the individual and the collective, and then how our cities can accommodate that and turn that into projects.

The role of crises is highly useful in that. We need to embrace crisis as an agent for change. Disasters can be extremely useful. They create urgencies for us to react to, they generate energy for us to invent and innovate. Maybe instead of waiting for disasters to react to, we could accelerate problems and use them as a motive for forward movement. It’s apocalyptic planning in a way. If there is a neighborhood with a really bad traffic problem, let’s make it worse. Let’s dedicate that neighborhood to be the biggest traffic jam on the planet for the next five years. I guarantee that you will end up with a better solution and more money out of that than if you were to do it a conventional way.

Most importantly, architects need to start looking forward again. That’s the thing about architects: they believe in construction and therefore they are always about hope. Even the most cynical architect on the planet cannot deny that his or her architecture is constructing alternatives and that no matter how small they are, how modest they are, how local they are, even how mediocre they are, they must have an ingredient of optimism. We need to take that optimism and reclaim the future of our cities.

Yes, let’s act. Formulate your position, decide what you want to do, and then do it. Some can do it with words. Some can do it on a small scale and bake bread or visit people in a hospital. Some of us can act directly on the urban environment. Whatever you do, get to work and do something about it.