Project by: César Arroyo

Thesis Advisor: Peter Trummer & Jordi Vivaldi

How does Reality design?

When we think about the Favelas, unconsciously we think about its social problems related to the lack of economic resources, however its urban morphology, created with a different conception of property and the law, is a subject vaguely studied. It offers dynamic urban relations that the capitalist-profit system of a traditional city, through its laws, prohibits. In traditional cities, shaped by neoliberal practices, the most important factor is to create capital. In this way the contemporary cities have been designed following patterns based on the maximization of land use and the ease of their trading. But after almost two centuries, these practices are becoming obsolete, unable to contain problems caused by themselves and that underlie the issue of population growth, that sometimes affects both developing countries and the most tourist cities. In this sense, can the intangible of the favelas be used to accelerate capitalist processes such as property law? to thus conceive a post-capitalist economy where the idea of subdivision of land shifts.

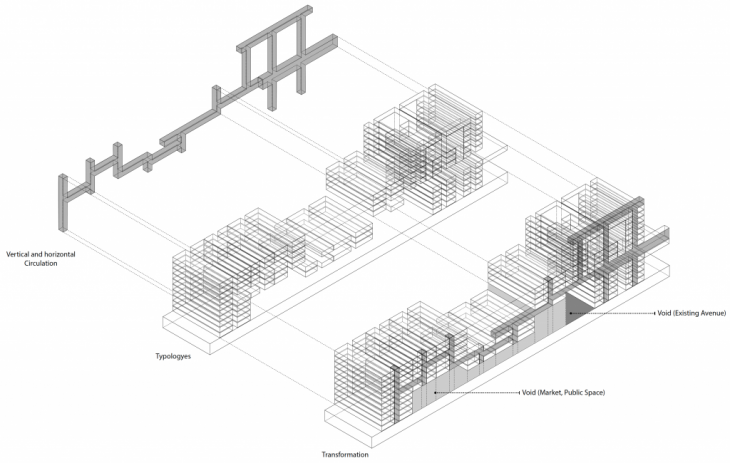

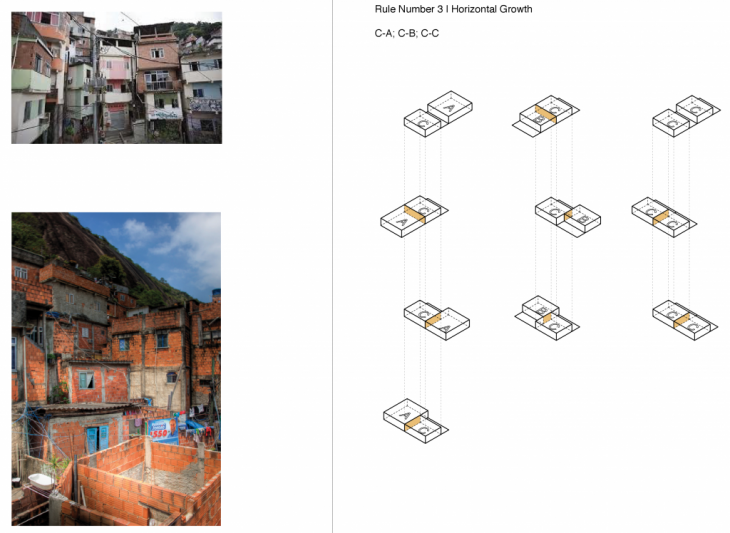

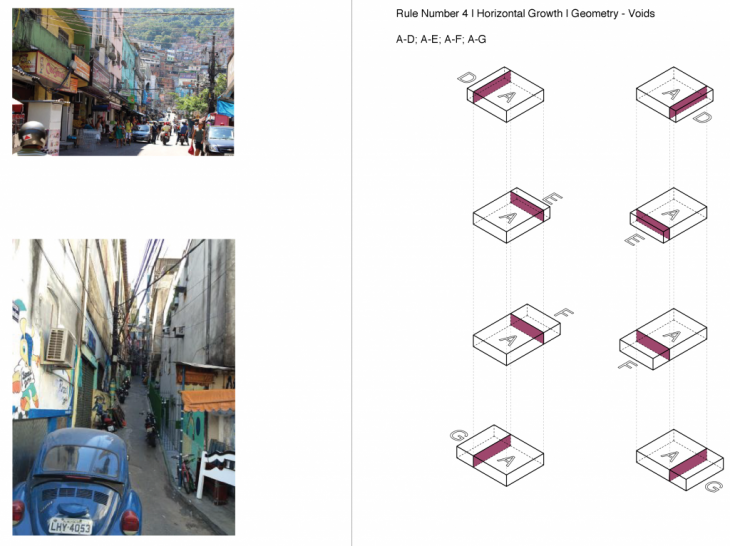

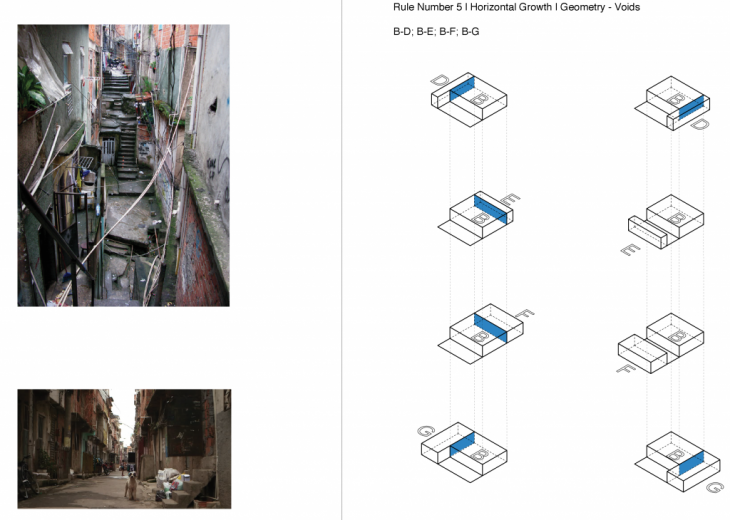

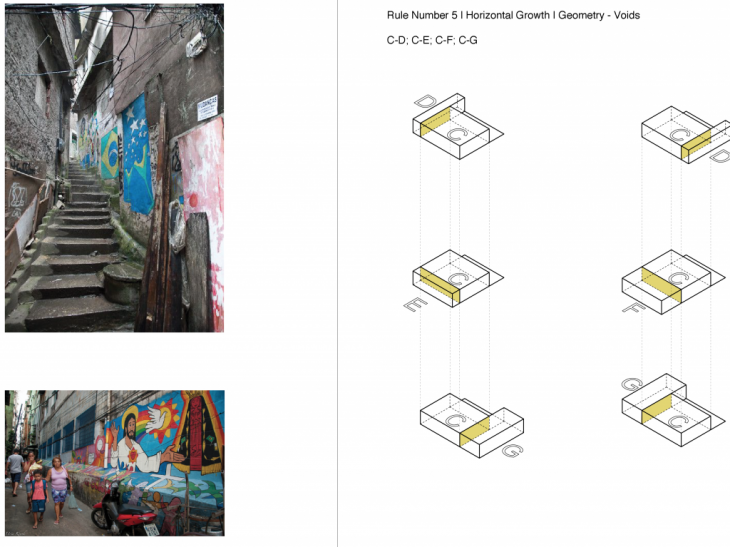

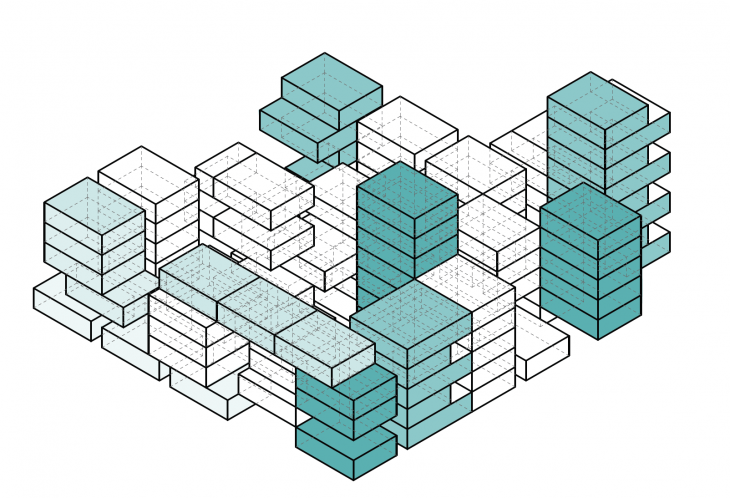

This project begins with the empirical observation of the favelas, from which 5 different rules that constitute an important part of the urban growth of the favelas were determined. These 5 “unwritten rules” will be the basis of the design of a new urban typology created far away from the informal settlements.

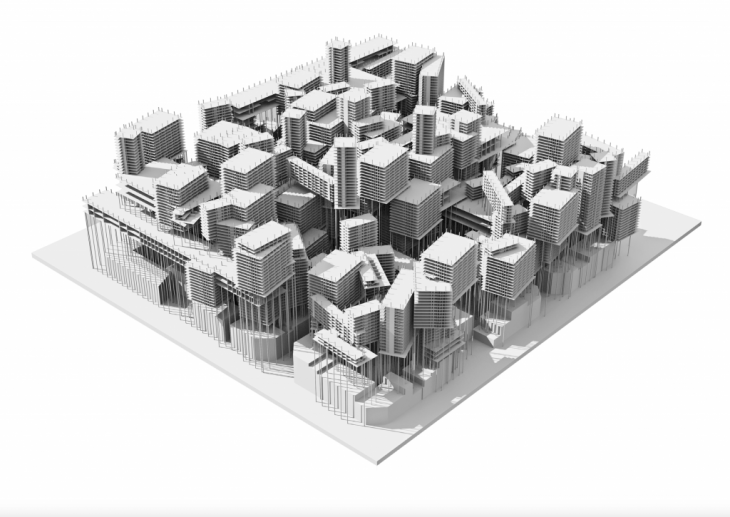

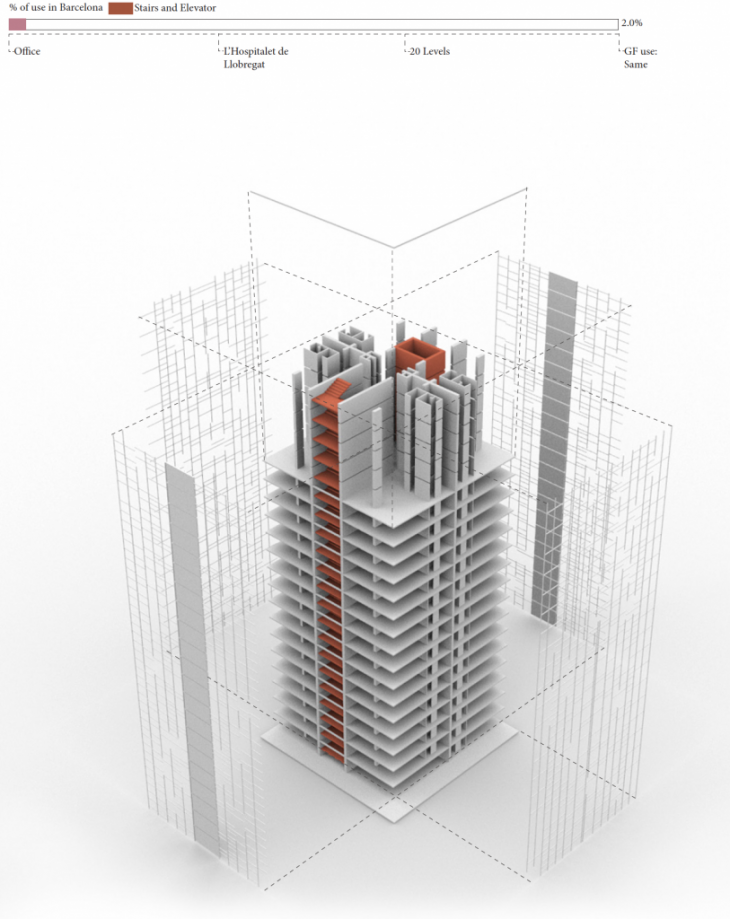

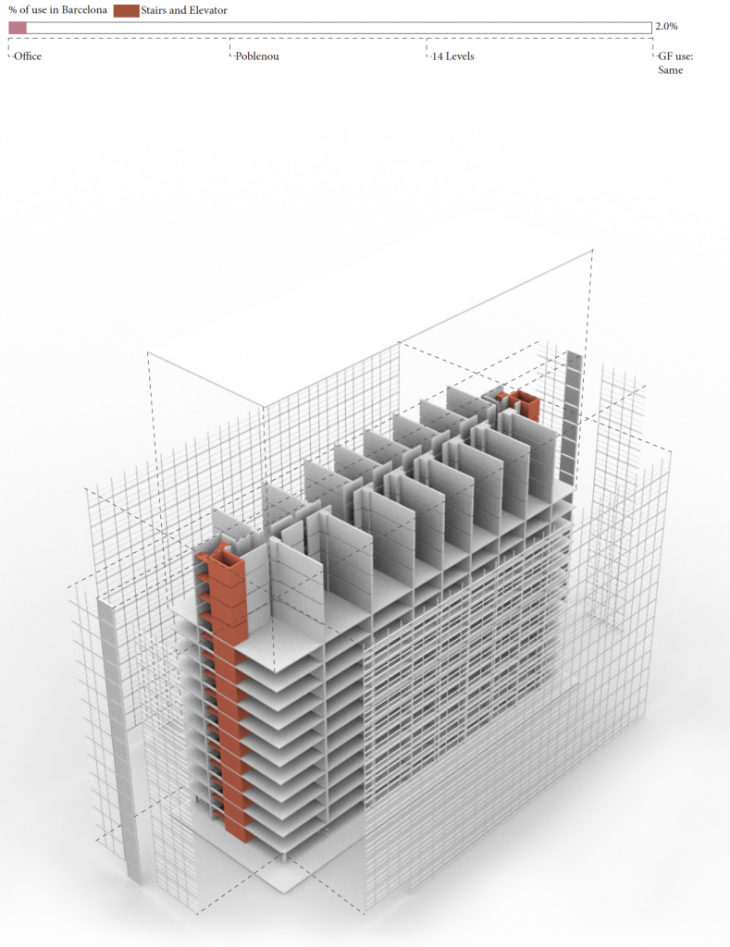

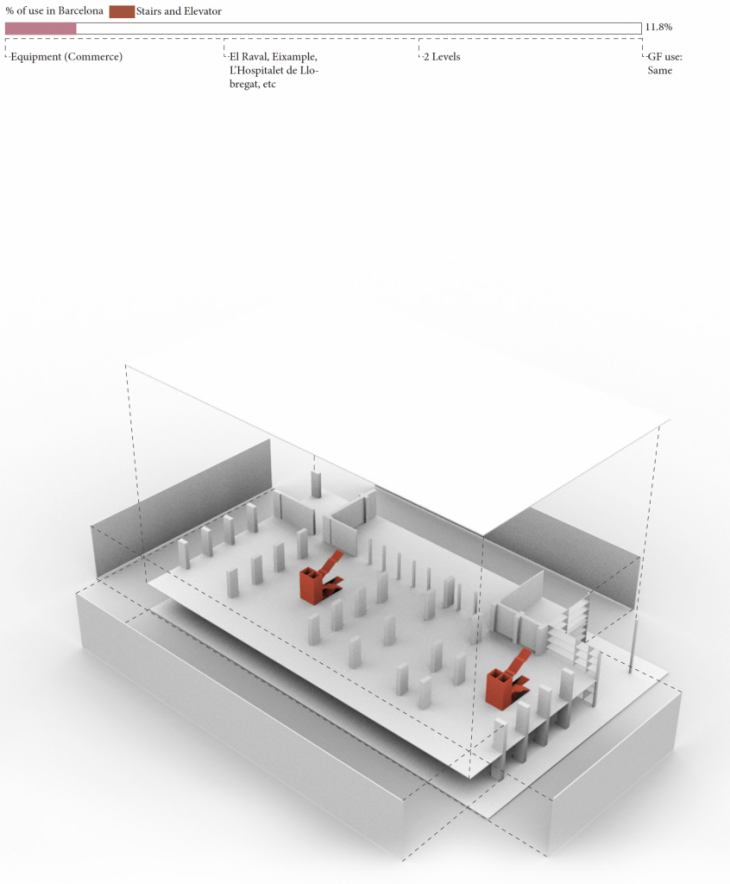

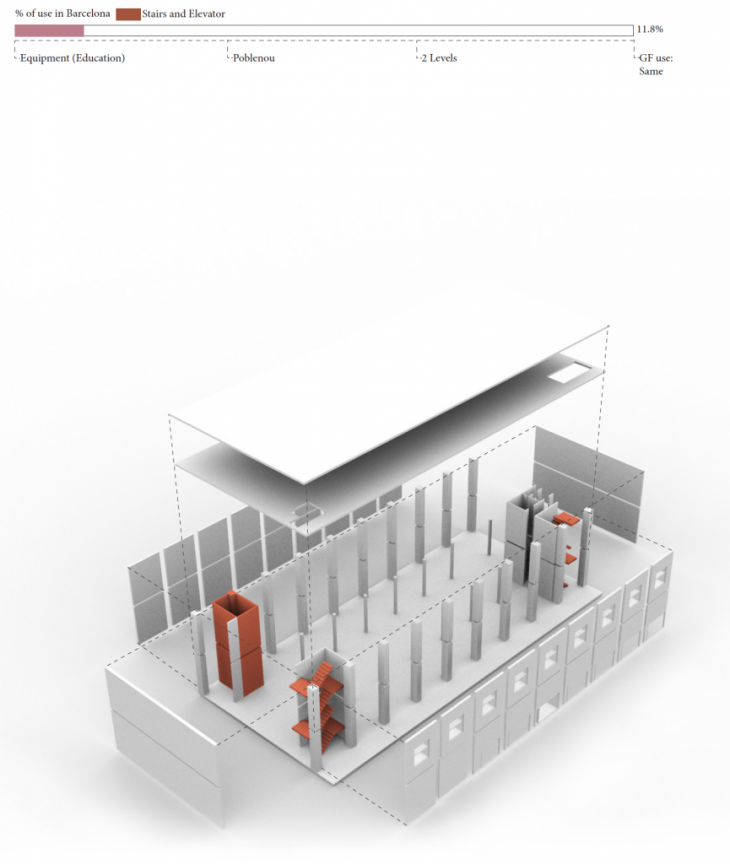

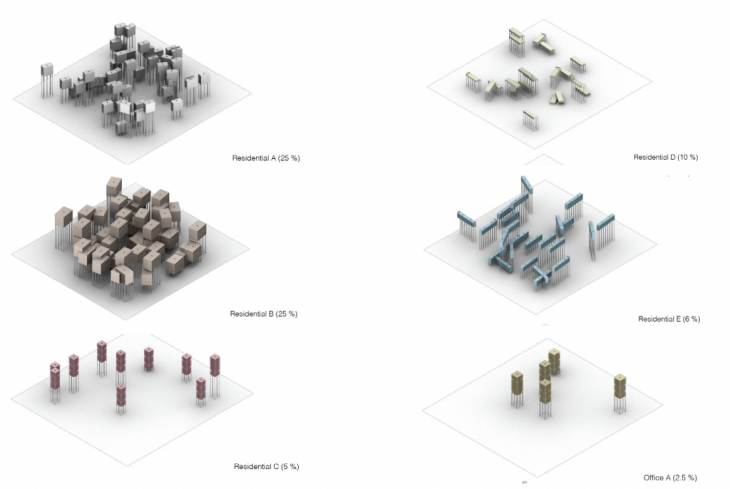

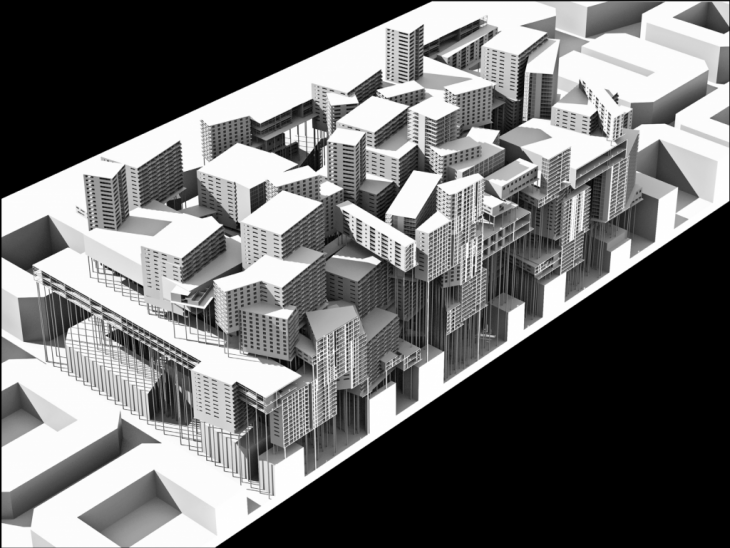

The project will be located in Barcelona, which through the Grid created by Cerda was one of the first cities to conceive urban growth and planning as an engine of capitalism; and taking into account that its economic flow is different than that of the favelas, the design incorporates 11 different types of buildings already built throughout the city (residential, commercial, entertainment, equipment), and are re-positioned following their existing context and the patterns dictated by the 5 rules mentioned above. Finally, the concept of the project seeks to break the capitalist paradigm that revolves around the property system, taking as a tool sub products created by the same capitalism (Favelas) to thus imagine a post-capitalist society that is capable of containing problems such as rapid population growth.

Population growth with expired capitalist models

According to the United Nations, during 2005–2050 the net number of international migrants to more developed regions is projected to be 98 million. Because deaths are projected to exceed births in the more developed regions by 73 million during 2005–2050, population growth in those regions will largely be due to international migration. The UN forecasts that today’s urban population of 6.2 billion will rise to nearly 9.3 billion by 2050, when three out of five people will live in cities.The increase will be most dramatic in the poorest and least-urbanised continents. One billion people, one-seventh of the world’s population, or one-third of urban population, now live in shanty towns.

Projections show that urbanization combined with the overall growth of the world’s population could add another 2.5 billion people to urban context by 2050, and because of the rigid legal systems of the cities people will continue populating urban areas illegally, converting more of them into megacities.

Currently 1/3 of the global population Lives in informal settlements and it is predicted that these levels will continue to grow. It is estimated that 70% of the world population are going to live in cities, this can not go unnoticed, the lack of urban space will bring problems in the future, that is why studying the settlements that act outside of the legal framework can lead us to give innovative requests for how to build the city of the future.

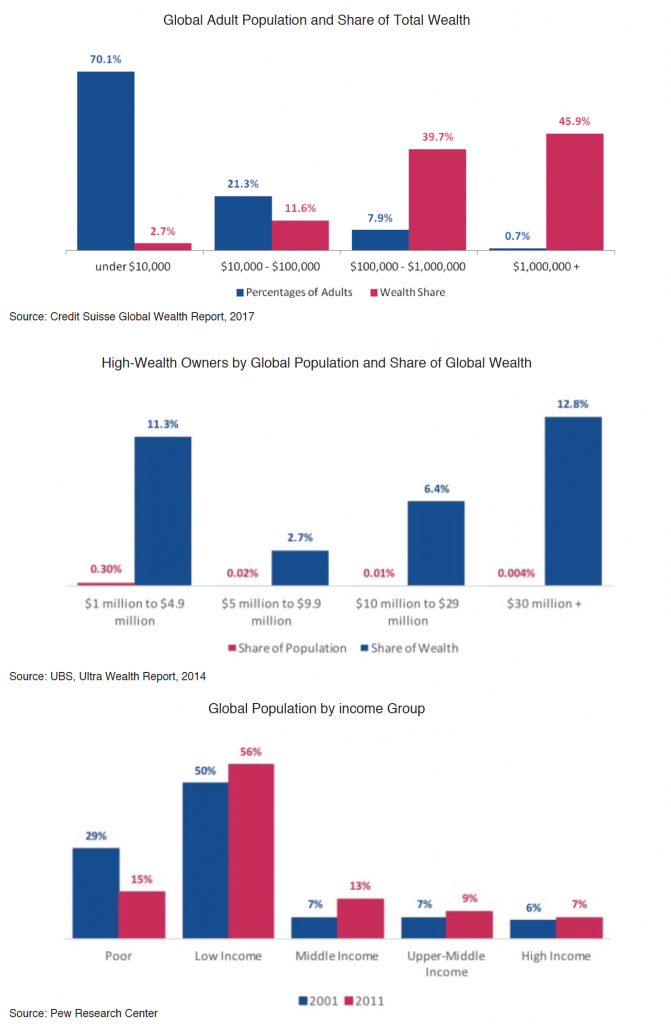

Global wealth inequality

It is important to speak, not only of the inequality that exists in the cities in terms of income and expenses, but also of the one that exists globally in relation to wealth. According to the inequality.org portal “More than 70 percent of the world’s adults own under $ 10,000 in wealth. This 70.1 percent of the world holds only 3 percent of global wealth. The world’s wealthiest individuals, those owning over $ 100,000 in assets, constitute only 8.6 percent of the global population but own 85.6 percent of global wealth.”

In the same way, the unknown lies in the definition of wealth and its scale. In relation to people in extreme poverty who daily make less than $ 2 and who make up 15% of the total population, a person of middle class is undoubtedly rich. We must also consider that 56% of the world’s population lives on a low salary and that only 6% have a high salary, however, and giving an example to the aforementioned, in this 6% of the population there are the richest people in the world, which, only the top 10 wealthier combine constitute a GDP higher than many countries, including Belgium, Iran, Norway and Colombia.

Without going to extremes, this great gap that exists between the poor and the rich, which is marked, basically by a minimum banking record, created unjust cities designed for and by the rich within legal frameworks that all they do is discriminate and expel the poor.

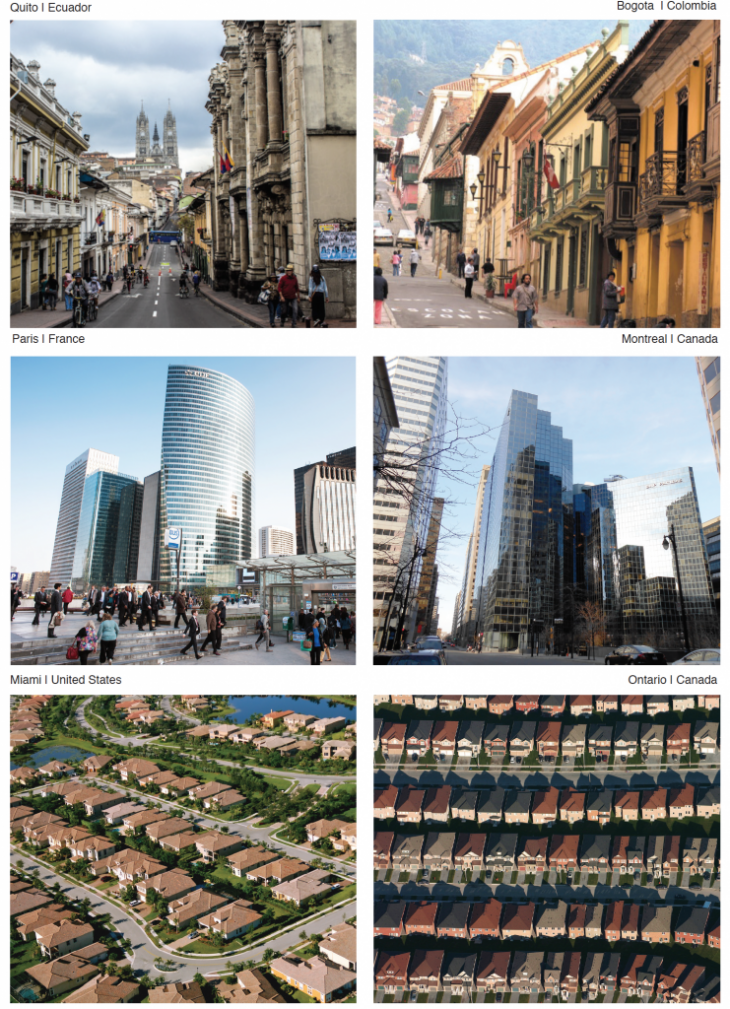

Building codes and the generic city

The image of the contemporary city has been developed based on capitalistic models of urban codes that regulate from dimensions to programmatic uses, these construction standards not only achieved safer and more orderly cities but also made them equal and rigid.

The treaty of the Indians, a book written by Leon Pinedo, details specifically how Spanish colonial cities had to be built in Latin America, this document, whose implicit value was the worship of the church, endowed similar characteristics to all urban centers by where the Spaniards passed. Currently, countries are choosing to put aside their local codes to opt for global construction models, something that produces, not only the death of identity of cities but also a world full of generic cities.

However, this phenomenon is not the most worrisome, the accumulation of rules, standards and codes make a city totally rigid and incapable of adapting to a near future where, the population is growing rapidly and populating more and more cities. In this way, the fundamental concern is the fact that in rigid cities, with little flexibility, the living cost is high, which leaves more than a third of the world population with the need to create a set of different rules.

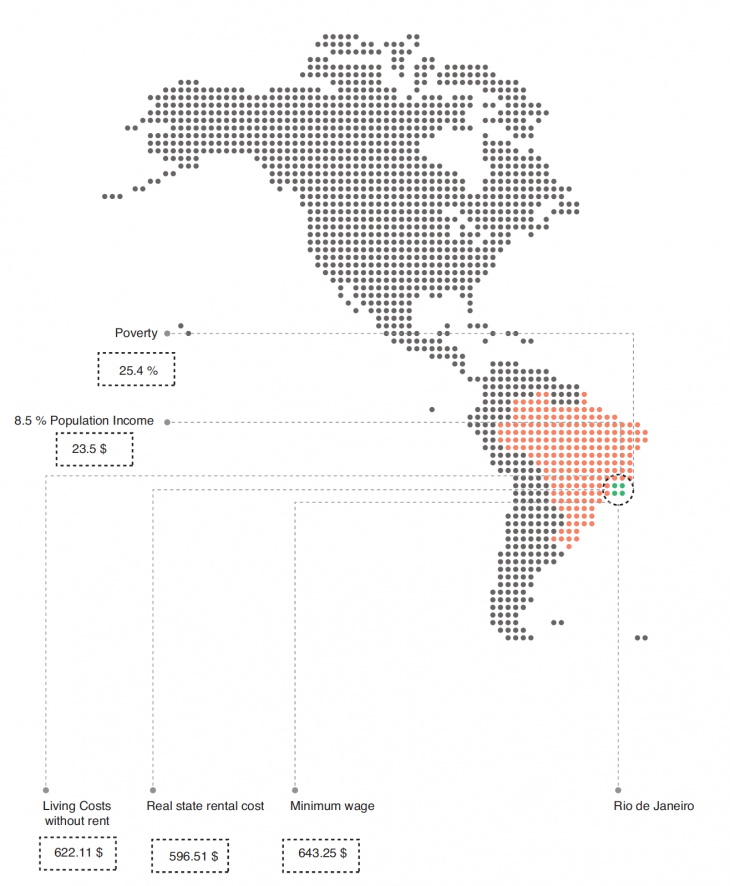

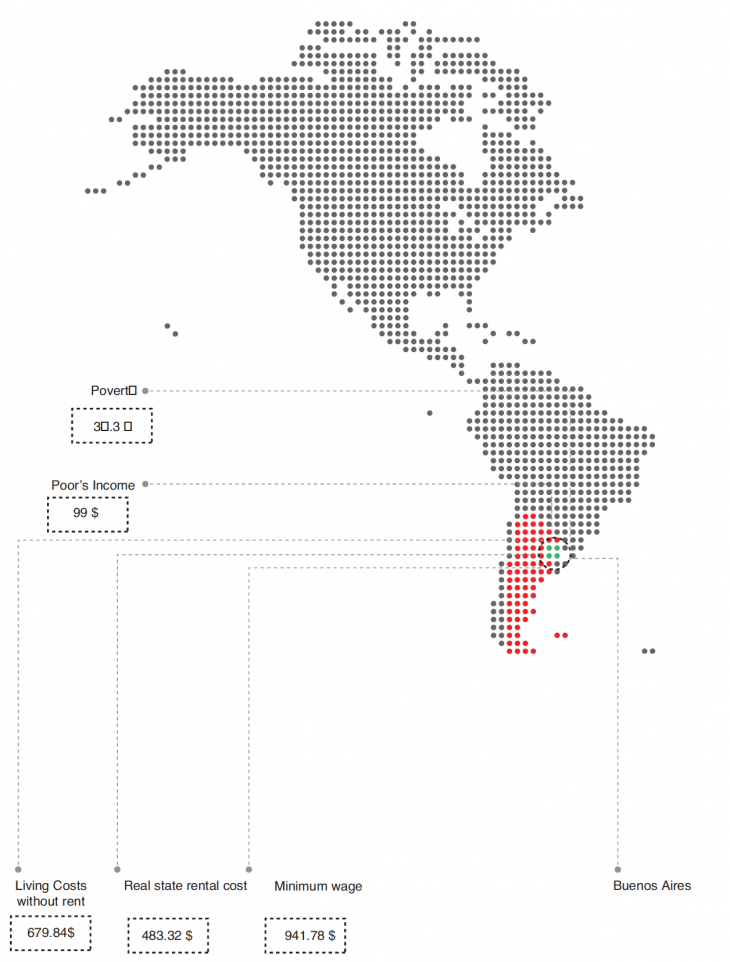

Urban inequality and over populated cities

Both urban and building construction models stipulate rules and regulations that, together with property laws, make the cost of living in in over populated cities extremely expensive for poor people who migrate to seek opportunities. This phenomenon of urban inequality is common in Latin America where more than 113 million people do not have the economic resources to live in

them.

In countries such as Mexico, Brazil or Venezuela, the cost of living in urban areas is disproportionate to the purchasing power of poor people. In some cases, the monthly minimum wage, stipulated by governments, does not cover the costs of the basic basket, and in other places the cost of renting houses greatly exceeds the ability of individuals to pay for them.

According to the newspaper La Republica, in Colombia the average salary of poor people is $ 132 and in extreme poverty is $ 64, however the minimum wage to buy necessary products is $ 118. In the case of Argentina the situation It is the same but adding the fact that Buenos Aires is the most expensive city to live in the region.

Informal settlements as a by-product of capitalist practices and models

Since the beginning of the cities, human beings have been creating a series of codes and regulations that norm urban development and that have consolidated the image of the city that we know today, According to Ben-Joseph “Standards and codes were meant to bring order and safety to the city building process.”, but over time these standards have become so rigid that there is no longer room for innovation and sustainable development of cities. Likewise this overwhelming set of rules and regulations have made the costs of building, reforming or even living within any city too expensive, which for most people who migrate to the cities is inaccessible.

This situation is what has forced people with scarce economic resources to populate lands illegally inside and outside the cities. UN Habitat estimates that 3 million people move from rural to urban areas on a weekly basis and in their inability to find affordable housing, they need to migrate to informal settlements. However, this conglomeration of individuals with the same values create communities based on a shared economy that have their “social capital” as their driving force.

With the consolidation of this social capital, the urban spaces, where the legal frameworks do not apply, become a territory that is “transformed as the community negotiates the spaces and their boundaries.” (Cruz, 2016), in which there is a constant innovation of complex and dynamic spatial relationships; concept that is opposed to the greater percentage of literature developed around this topic that focuses on defining them as precarious and disorganized. So this different type of organization, in spite of not being legal, also has a series of spatial and programmatic codes and rules that regulate its urban growth.

Within this context, it is important to emphasize that the accumulation of rules and codes, with which cities are currently formed, makes it incapable of adapting to the accelerated urbanization of urban areas and that the answer lies in turning our eyes towards the idea that “informal settlements are not a problem but are the solution” and that this is hidden within the logic of spatial relationships based on a property law opposed to that of the formal framework.

Empirical study of aggregation using algorithmic models Favela Rocihna

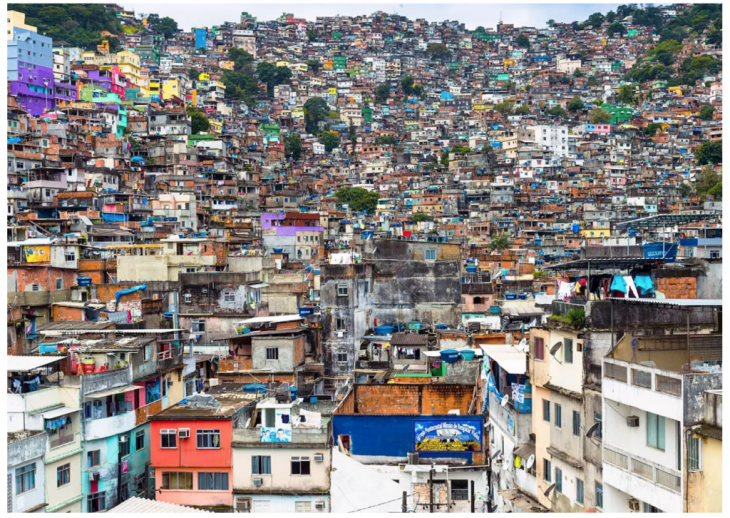

Rocinha is the largest favela in Brazil, it developed from a shanty town into an urbanized slum, is located in Rio de Janeiro’s South Zone between the districts of São Conrado and Gávea. It has a total area of 143.72 ha. Home to 150,000 people, Rocinha is probably the most famous slum in Brazil. A city where favela residents make up 22.03% of the population, this means that out of the 6.3 million people living in Rio, 1.4 million lives in favelas.

The favela sits nestled between three of the wealthiest residential areas of the city and due to its sloping topography the spatial relationships between buildings is complex and dynamic.

Likewise, despite the fact that on the outside it seems that their image is precarious and full of randomness, the reality is that inside there are countless rules that its inhabitants have been creating over time.

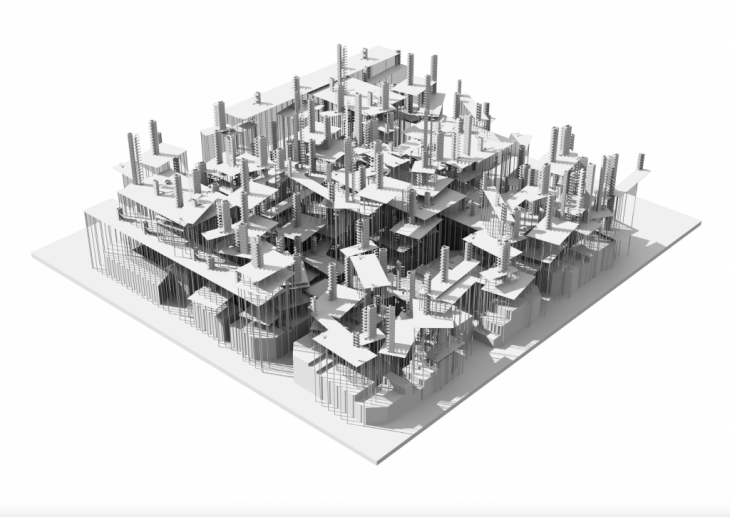

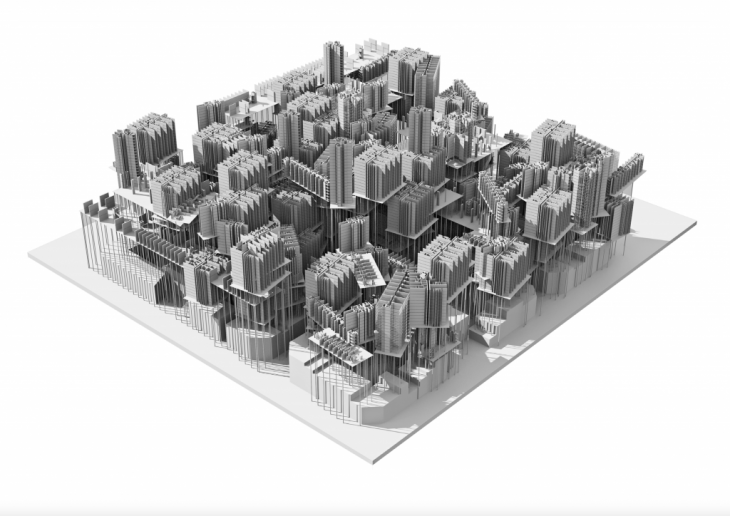

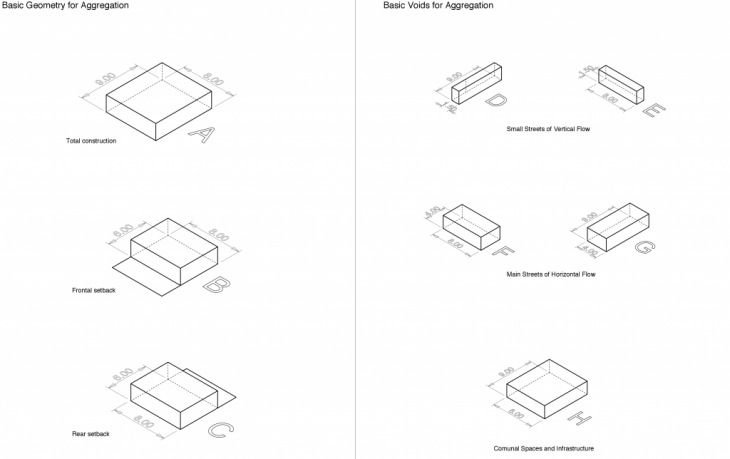

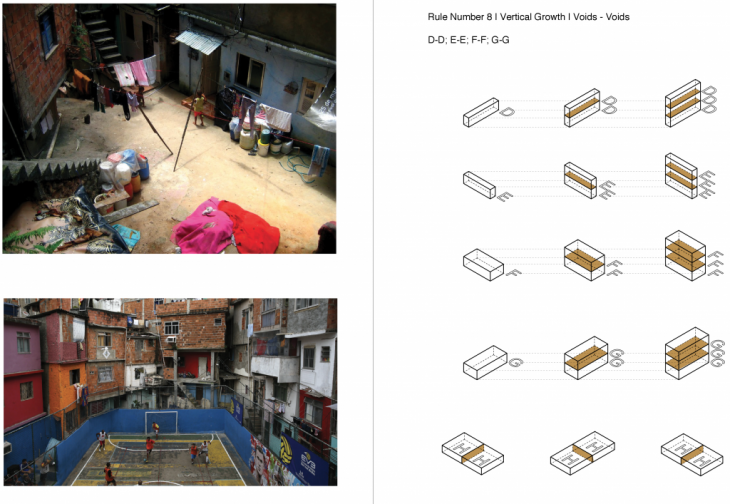

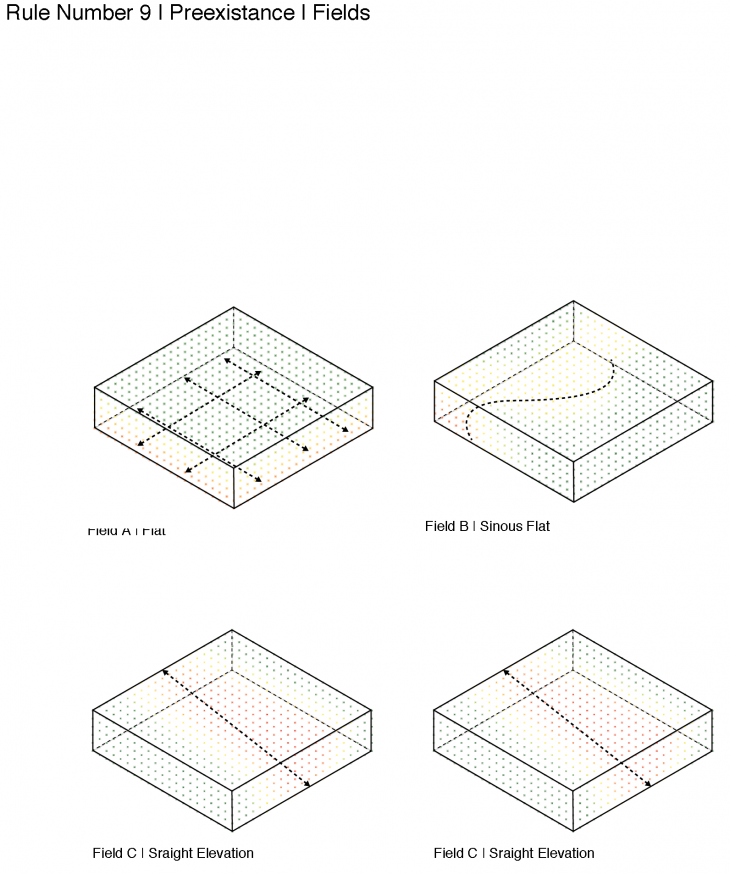

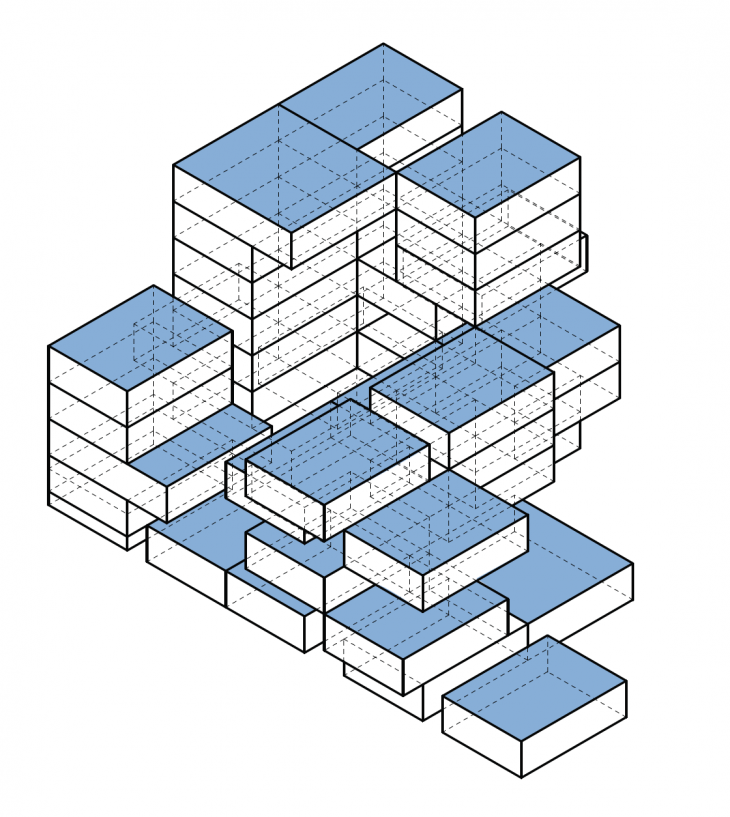

The first step was to define a model of aggregation based on the creation of generic forms that represent the construction patterns in the favela, in this way and through empirical studies we took as a starting point a housing unit of 9 by 8 meters divided in 3 longitudinal axes of 3 meters and 2 transverse axes of 4 meters. On the other hand, the interstitial spaces between the buildings that are commonly used to adapt stairs or vertical flow elements were analyzed, and empty spaces that represent main streets and public spaces where added into the equation.

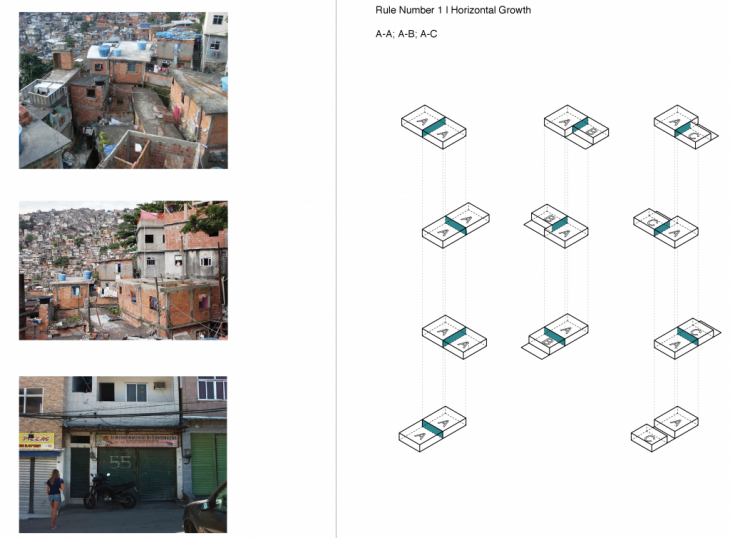

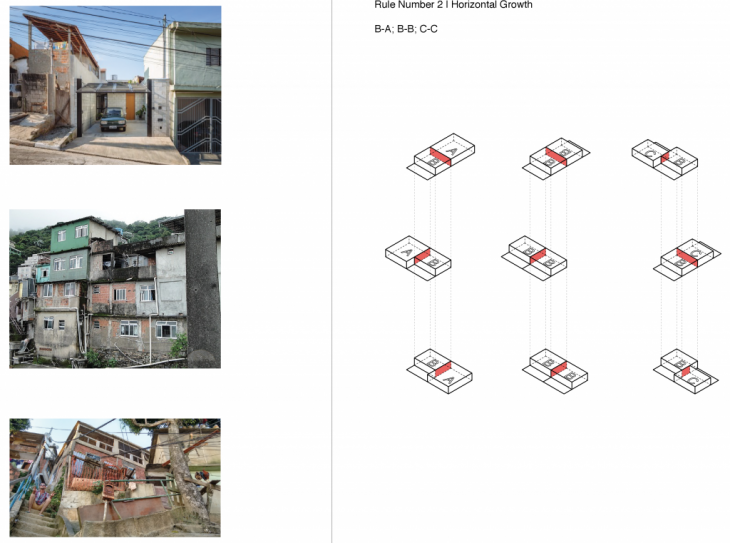

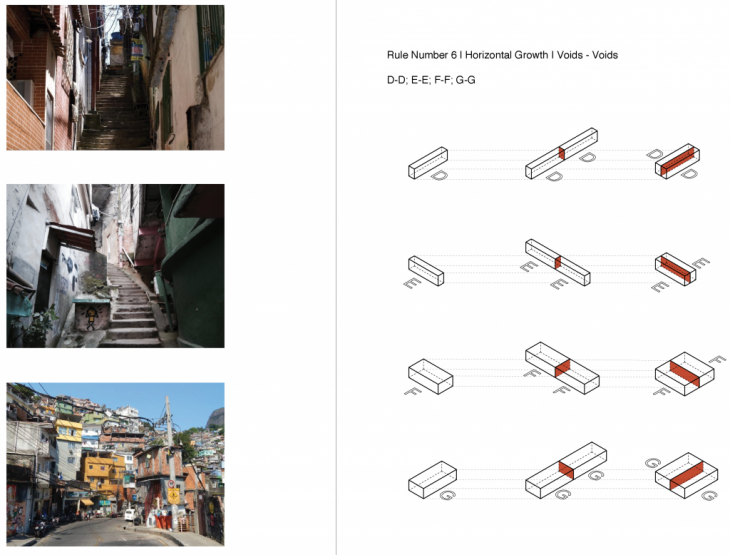

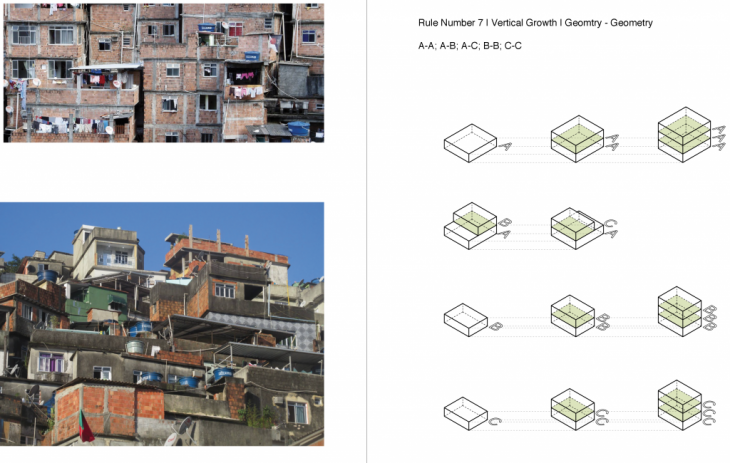

The next step was to define the rules of aggregation considering both vertical and horizontal growth of the main spaces and empty spaces. Finally, 5 generic aggregation models based on the Rocinha structure were chosen.

Hidden Laws | Logic

“This is a buttom up urbanization that performs, here the buildings are not important just for their looks but, in fact, they are important for what they can do.”

(Teddy Cruz, 2013)

It is necessary not only to remain in the empirical study of the spatial relationships of the favelas but it is fundamental to go a step further and try to discern the logic that exists within these complex relationships. This project does not seek to reproduce the idea of a favela, it tries to disconnect from social problems, poverty, unhealthiness, and also from the quality of homes that are created within it. This study is based mainly on the hidden property laws that have triggered the creation of a morphology such as the one of Rocihna.

As mentioned above, the property laws of formal cities are disconnected from the reality in which the world population lives, and it is vital to turn our eyes to the urban areas that are constantly growing, which have developed strategies to fight the inconsistencies of capitalistic practices. Within this study, 5 laws or logics that excelled in the aggregation models previously explained are mentioned.

The next step of this thesis is to create an architectural typology based on the logic extracted here, a typology that can be applied in any legal urban environment and for any socio – economic class.

Law 1 | Multilevel Developing Land

Within the informal settlements, the spirit of the people always revolves around the hope of building vertically. In some cases, this growth develops over many years and with the desire to house future relatives. In other cases, this aggregation of units serves as a generator of money in terms of tourism or real estate.

The First law defines a constant vertical expansion, where the last floor of each building becomes a developing land. This avoids a spatial rigidity that commonly leads to buildings being devalued and later overthrown.

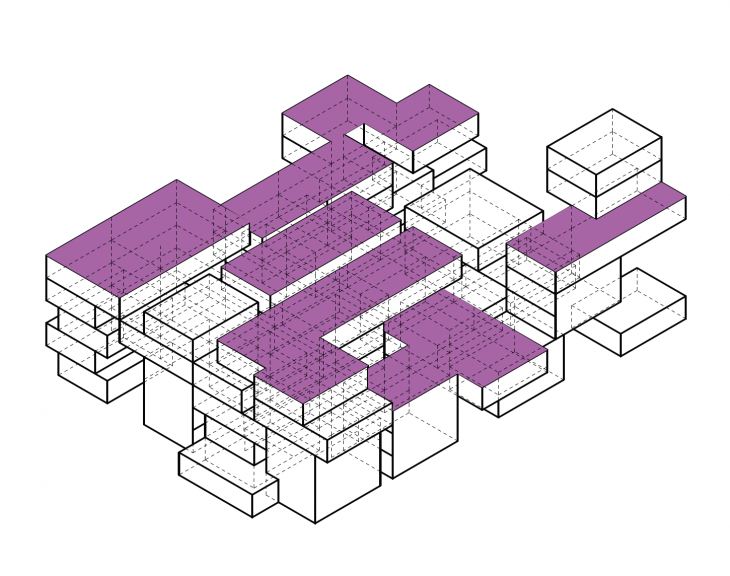

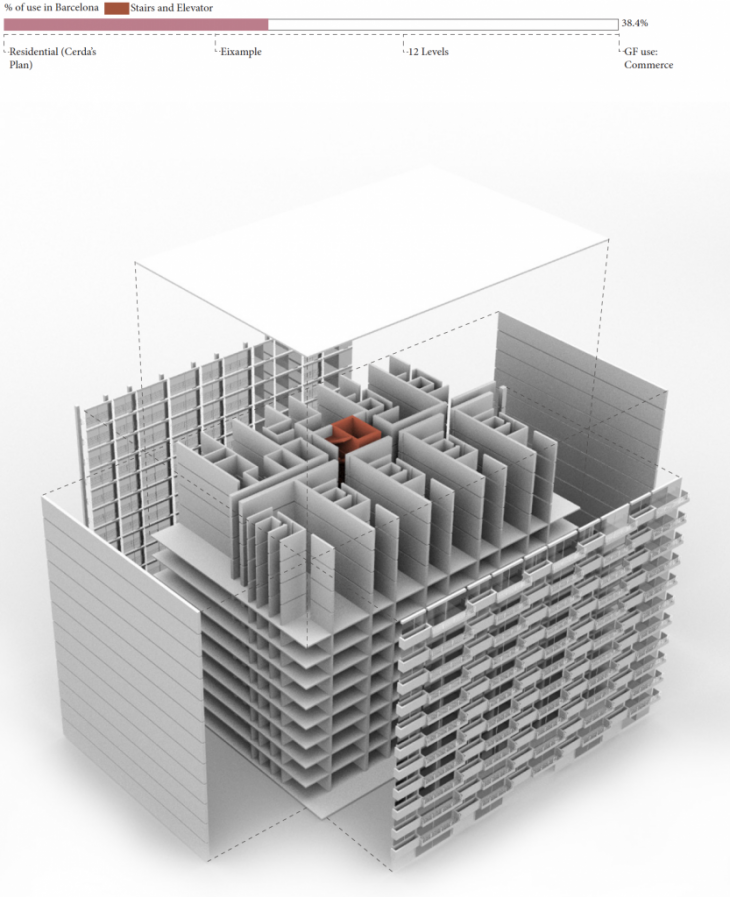

Law 2 | Multilevel Volume Unification

Within the vertical relationships between typologies, there is the ability to unify nearby spaces, which creates different flexible urban layers that interact with their context.

This allows alternatives for mobilization between private spaces, allowing access to places that would otherwise be impossible.

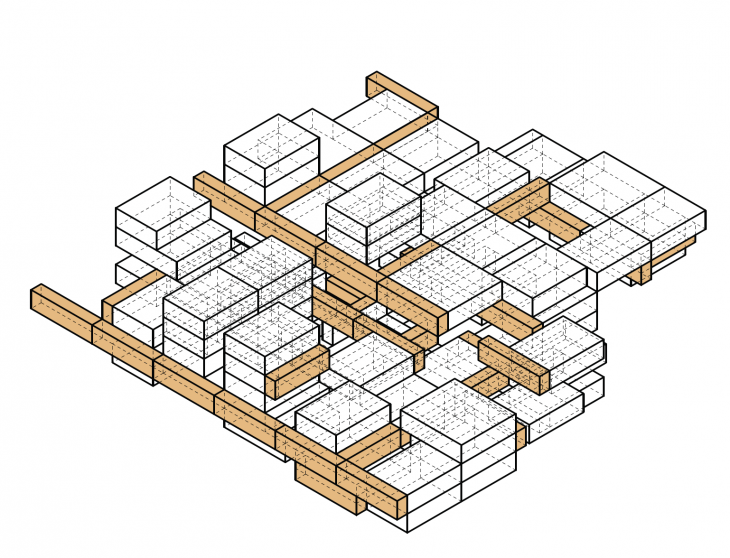

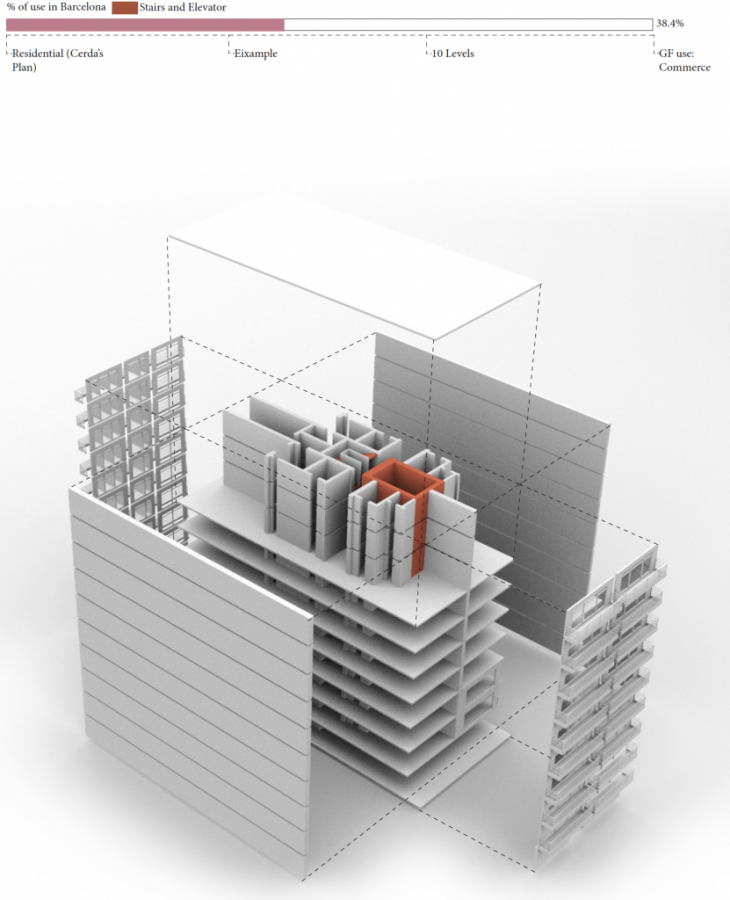

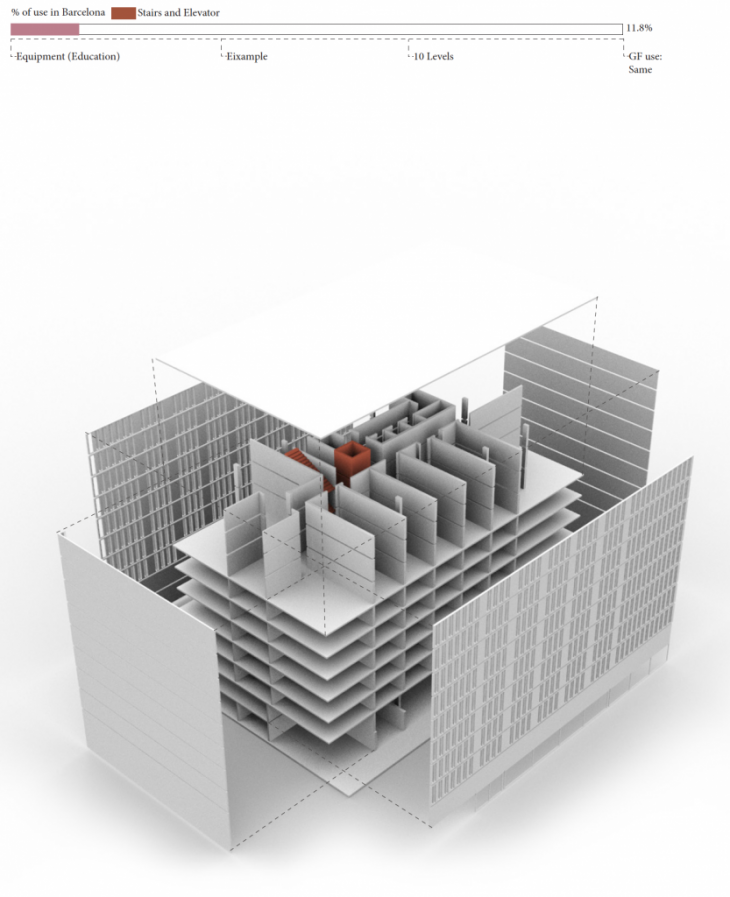

Law 3 | Private as infrastructure

Due to the constant vertical expansion it is necessary to create vertical flow elements such as stairs and elevators that connect to public access roads at different levels. As well corridors and hallways are used to connect private and public spaces along the way. In these sense the line between private and public is intermittent and disappears.

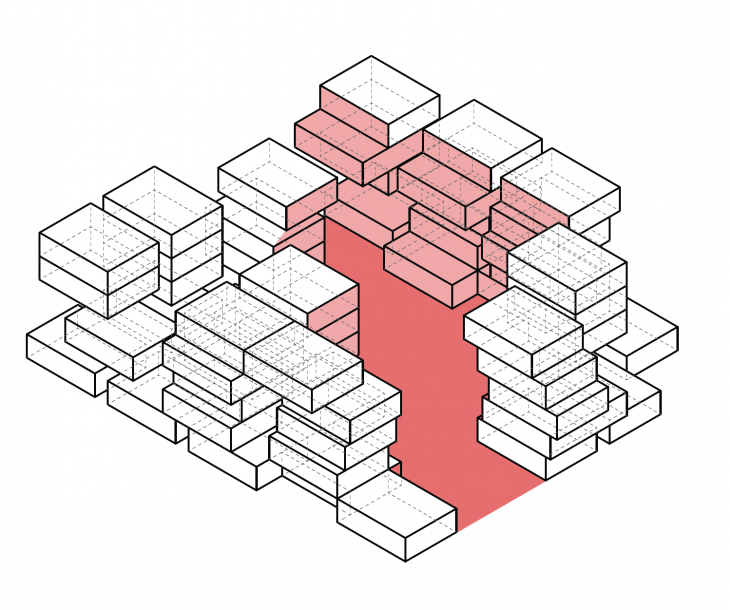

Law 4 | Communal void as hierarchical center

The infrastructure and communal areas are the only inflexible points, they act structuring and generating spatial order. This is the only place in the favelas that that behaves as if it were within an established legal framework, that is, the community respects its limits. They also create vertical visual connections within the system.

Law 5 | Tipological Variation

Within a same urban and architectural context there can found a myriad of varied architectural forms. This is due to the different subdivisions of lots that are created at the beginning of the settlement and also because there is not a established code that norms the way people is supposed to built.

Site

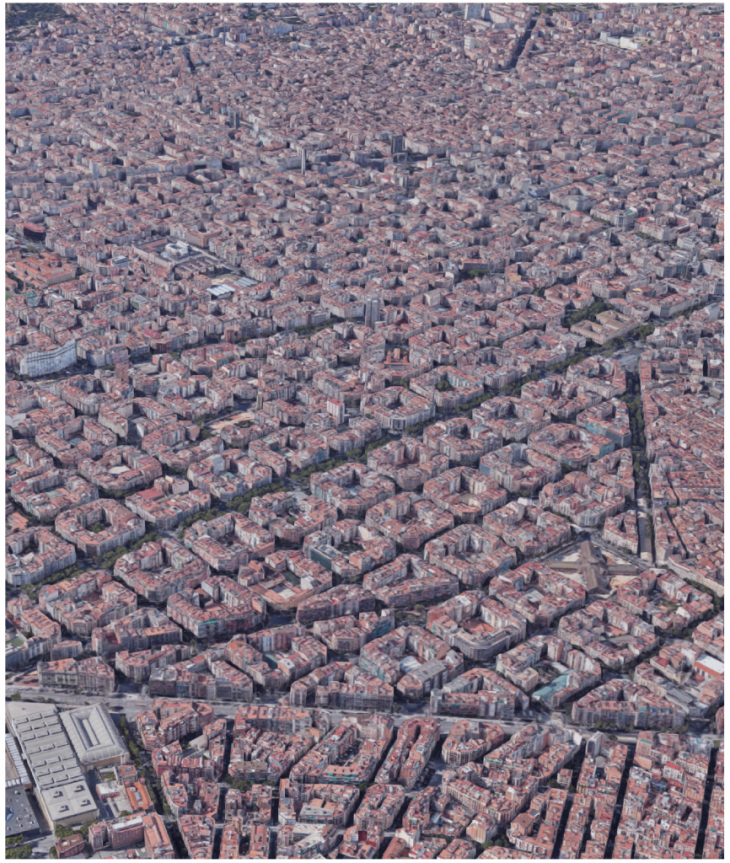

Accelerationism and the grid

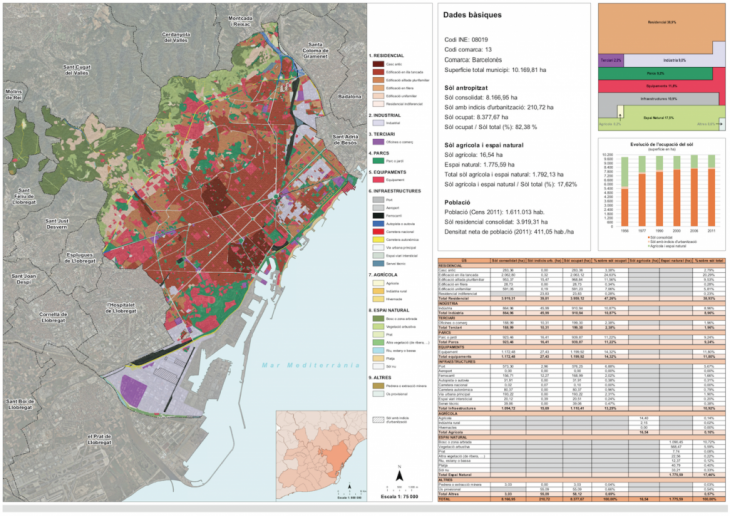

Barcelona is the capitalist city par excellence, not because of its government policies but because of its urban development. Cerda, contemplated a plan where every square meter, within planning, is efficiently tapped. For this he created blocks with a perfect exterior size and with an empty interior allows ventilation to the departments that are in the back of the buildings with blind side walls. With an orthogonal approach achieved a very efficient building, conceiving for the first time the development and urban planning as a generator of capital. This created a paradigm that has been gaining strength for almost two centuries but is now becoming obsolete because it can not contain the rapid population growth in the world and that in Barcelona revolves around tourism and the ephemeral passage of people who do not have a solid roots in the public and private spaces. Within this context, new practices are needed that change the conception of the subdivision of land based on new property laws.

According to Maurores, accelerationism … maintains that there are desires, technologies and processes that capitalism brings forth and from which it feeds, but can not contain; and that it is necessary to accelerate these processes to push the system beyond its limits. “in order to conceive a post-capitalist future. So my project seeks to locate in Barcelona and through the logic and property laws of the favelas (which are a byproduct of capitalism) accelerate their obsolete capitalist processes to create a building typology that conceives totally different subdivision of land and rights of property.

Empirical study of building typologies in Barcelona

Using the reality to build a new one

Percentage of uses (program)

Transferring the percentages of uses around Barcelona to The Magablock.

Using the laws as design drivers

LAW | MULTILEVEL VOLUME UNIFICATION

LAW | PRIVATE AS INFRASTRUCTURE