When you walk up to the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art, you are presented with one of Barcelona’s great urban spectacles. The modern, all-white building with its multi-story glass facade is reduced to a mere set and setting for a seemingly unlikely cultural phenomenon: skateboarders. Groups of spectators, local kids, tourists, wannabes, and lurkers of varied origins all show up to watch. They mill about the plaza or chill in front of the museum, sitting in lines across the plaza’s concrete benches. Some are there to visit the museum, but most are not. This whole scene may surprise you if you expected Barcelona’s contemporary art museum, known as MACBA, to be a formal and pristine locale. You could be forgiven for wondering what the hell is going on here.

Richard Meier’s MACBA was built in the El Raval neighborhood of Barcelona in 1995. The area has a long, rich history as part of the Old City of Barcelona, but in more recent history El Raval had developed a rather seedy reputation. Known for drugs, crime, and poor immigrants, it was generally avoided by tourists even though it is directly adjacent to El Gotico- the touristic heart of Barcelona. In an architectural sense, the museum was considered a gleaming jewel of contemporary art in an otherwise rundown area.

The MACBA museum plaza is formally known as Plaza of Angels. It’s a wide-open public space crafted from granite tiles with smooth ramps, stairs, and multi-level benches. In other words, it’s a skater’s paradise. It didn’t take long for locals to catch on and the plaza soon became the skate spot in Barcelona. Fast forward to today and MABCA is an internationally notorious skate spot that draws casual skaters and professionals alike from all over the world.

But it hasn’t been easy. In the earlier days as MACBA started to get popular, locals and museum officials resisted. Skaters are loud. They drink beer and play music. They get rowdy after dark and draw crowds of hooligans and “undesirables.” Neighbors complained, and the museum (rightfully) feared the degradation of the architecture and granite fixtures. Skate spots get beat up, and skaters can often be anti-social and aggressive towards outsiders, so it wasn’t unwarranted when the museum soon banned skaters from the plaza.

But it was too late; the global skateboarding community was already firmly entrenched. A local social media account, MACBA Life, rallied support from the community and petitioned the city for a compromise. Eventually, through a somewhat awkward process of formal and informal negotiation, the museum agreed to allow skating during the day. In return, the skaters pledged a semblance of community ownership and responsibility; to clean up after themselves, be respectful of the neighbors, and so on.

This isn’t the first time a community of skaters has had to negotiate to continue their appropriation of public space. Skating was long considered a fringe cultural activity and everyone has seen their fair share of “no skateboarding” signs. But that impression is largely a hangover from the 90s. Today, skateboarding is not only a multibillion-dollar industry, it is also an Olympic sport. Beyond that, we think it is fair to acknowledge that the global skating community is firmly embedded within the context of arts more broadly. Creative people all over the world are fascinated by the way it blends athleticism, self-expression, fashion, creativity, and the innovative use of urban space. That framing makes the skating community seem less like a nuisance and more akin to cultural rocket fuel for artists. In today’s art world, the skaters who use the museum plazas are the protagonists, not the museums themselves.

The founders of the MACBA Life Instagram account organized the original petition to keep skating legal at the museum. Today their account has twice as many followers as the museum itself.

Typologically speaking, MACBA is not alone. Museums all over the world are built under the same design brief; a museum building adjacent to a public plaza. The building is a curated repository for art or cultural artifacts, and the plaza is a public space ostensibly open to all.

But as we know, the limits of “open to all” are called into question when the skaters show up. In that conflict, museums tend to resist the encroachment of “undesirable” groups and activities. Hence the skating bans. Skaters simply see the built environment as their canvas, a playground for self-expression. This sets up a tense negotiation where a compromise has to be found, and that compromise often has plenty of hostility baked in.

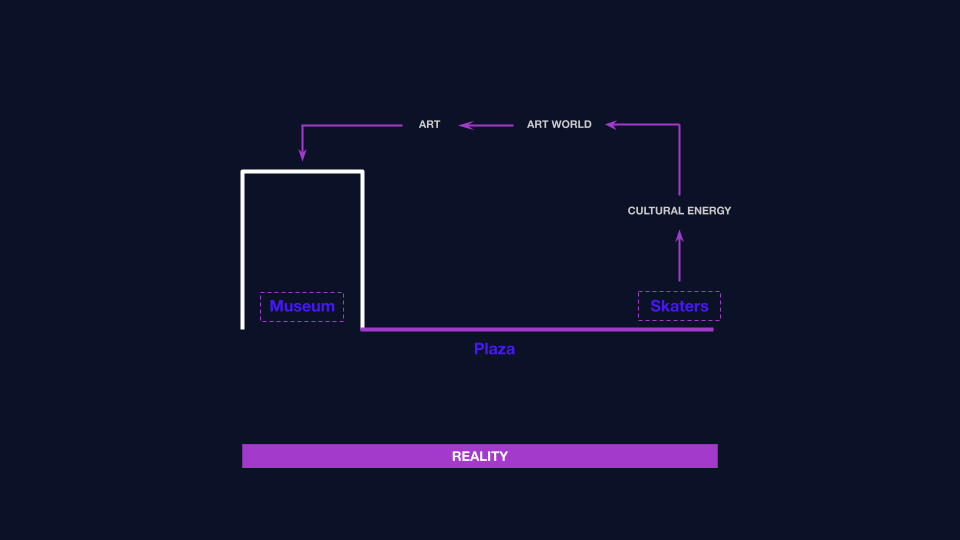

Still, we feel that this conflict misses the broader reality of the situation that we touched on above. The truth is that skaters generate cultural energy. That cultural energy attracts and inspires street artists, small retailers, and creative people from far and wide who appreciate the renegade nature of skate culture. The skater community has a major influence on how art is created in society from a grassroots level. It is a mainstream pillar in the broader context of art culture. That broader context is the source from which new artists emerge to produce the art which eventually occupies the museums themselves.

One need only to look around the El Raval neighborhood today to get a visceral sense of this, at least in terms of economics. The neighborhood has become a burgeoning and energetic cultural haunt for young people. Was it the museum or the skaters that turned the neighborhood around? Maybe it was neither, one can only speculate, but the concentration of upstart fashion brands, vintage stores, skate shops, and edgy art galleries in the area is something to consider.

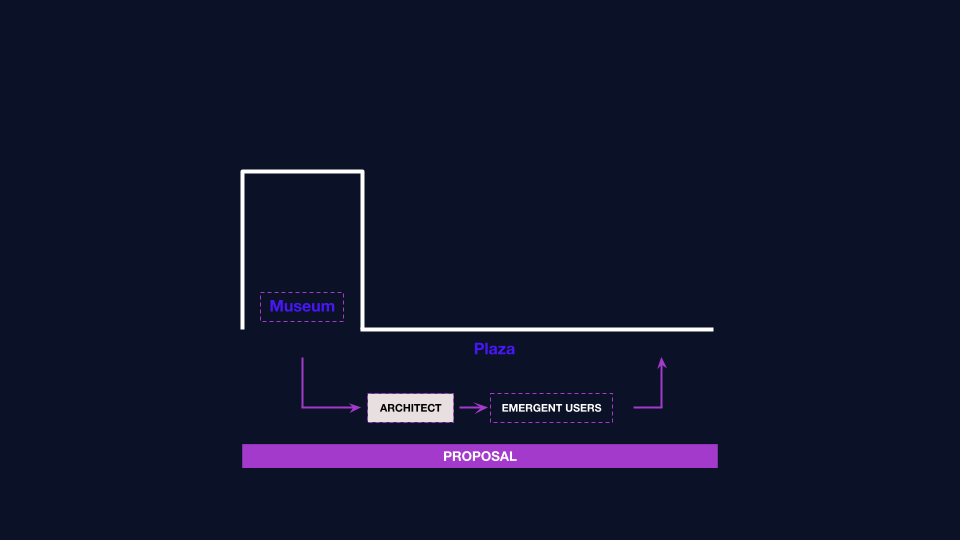

Taking the reality above one step further gets at the core of our proposal. We see that there is a clear link from the cultural energy of the skaters into the very soul of the museum, but without a reciprocal link from the museum back into the public space, the model is incomplete. As it stands, the role of the architect is to design the museum and the plaza as a one-off design exercise. Beyond that, the museum building is operated by the institution, and the plaza remains relatively static beyond basic event programming. What if the architect took on a new role? What if the museum could give back to the users of the public space in a way that acknowledges and reinforces their cultural connection? Such a system would create a loop of reciprocity that may enrich both the museum and the user groups which emerge in the plaza.

The architect’s role has become more specialized and more professionalized over time. But architects are creative people who can blend art and engineering in a way that is often lost in a design process constrained by finances, building codes, and project timelines. Their unique skill set is poised to unlock new sources of value for clients and for society if the role they play could be reimagined. What the museum needs is a partner who can manage an ongoing design process that curates and encourages the reciprocal link between the museum and emergent users of the adjacent public space. Architects and their clients will always pay lip service to the fact that they care about creating a relationship with the users of the spaces they design, but in practice, there is no mechanism that effectively enables such a relationship. Our model proposes such a mechanism.

The traditional design brief for the architect, and therefore the architect’s role and income, is weighted towards the initial design and construction of the museum. We propose a new design brief wherein the initial design and construction are only the first chapters in the architect’s work. Post-construction, the plaza becomes a public space for emergent user groups (such as the skaters at MACBA). The architect’s role then evolves into a sort of cultural anthropologist, tasked with observing and reconfiguring the public realm over time in an ongoing dialogue with emergent temporally defined use cases.

Architects would engage in data collection and original research that explores how the public space is utilized and coopted by users. That information and the accompanying narrative could inform intentional and temporary reconfigurations of the public space in support of these emergent uses. This research could become a source of feedback that enables the museum to recognize and support emergent users who may eventually enrich the cultural content of the museum itself. In this way, the museum could encourage and foster upstart cultural activities over time via this new role of the architectural team.

If it were to become the norm, this new model could unlock previously unimagined value for all the stakeholders involved. Museums might find themselves with a strong new pipeline of cultural energy and artistic output. Making explicit the link between street culture and museum culture pumps fresh blood (and fresh art) into institutional veins. Additionally, original cultural research and proprietary data generated by the architectural team could become an exciting new realm of patronage for the museums.

Architects on the other hand would gain a mechanism by which to truly build an ongoing relationship with the users of the spaces they design. And by shifting into the role of observers of human behavior they may find their expertise challenged to expand into a fascinating new realm of urban research. This new line of work could generate a critical new source of ongoing income for their firms.

As far as the emergent users (or co-opters like the skaters) of public space go, they may find their endeavors met with appreciation and resources instead of hostility and misinterpretation. What new arts and cultures might emerge as a result? We can only imagine, but that’s the point; fresh ideas can be fragile as they emerge, and we only know what they could be if they are nurtured instead of crushed.

On the flip side, this new model also raises a lot of questions and concerns. Is it ethical for architects to surveil public spaces? How would space and resources be divided between competing users groups? What if one user group dominates the public space? Will architects be vilified as the new gatekeepers of recognition for emerging artists? Will architects be burdened with the ethical implications if things go poorly? There’s a lot to consider.

In any case, we feel it’s high time to rethink what it actually is that architects do for society. Will their role eventually be reduced to the design of facades and interiors as buildings become increasingly dependent on specialist engineers? Or will they become something new and more? As for fringe cultural groups, like skaters, will they always be shunned as countercultural? Or will the institutions of art who rely on them acknowledge their value to society?

A reciprocal, cyclical, and ongoing design brief. Architects as long-term custodians of the public realm. Museums and architects partnering to pioneer a new field of cultural research. Institutions as the progenitors of the new underground. These ideas, ranging from intuitive to anti-intuitive, open up a host of new opportunities and challenges. We’ve thought it through, and ended up with more questions than answers, but that’s the right place to end up after a 72-hour design studio.

MUSEUMS OF [CON]TEMPORARY ART is a project of IAAC, Institute of Advanced Architecture of Catalonia developed at Master in City and Technology in 2021/22

Students: Gayatri Agrawal, Julia Veiga, Ocean Jangda, Can Xu, and Faculty: Nicolay Boyadjiev