ISTANBUL is one of the world’s largest cities by population, ranking as the world’s fifteenth-largest city and the largest city in Europe. In recent years, Istanbul has also become a place that has created serious discussions about its third bridge, but the social, environmental (and maybe governmental) effects of this bridge, which is responsible for connecting different continents, are still not clear and not investigated in-depth. Which has been one of the main factors that encouraged us to “re-consider Istanbul” with all its layers, patterns and systems having a relation/integrity with the third bridge.

In doing so, it would be a good start to focus on the basic principles, or rather a frame of mind, that following the re-analyzing, re-assigning, re-evaluating and re-thinking steps for the study in question.

RE-ANALYSING MOBILITY OF DIFFERENT (F)ACTORS

As a large urban center, Istanbul faces a rapid increase in motor vehicles, representing a clear modal shift to car use: currently, the number of cars rise faster than the population growth itself, and intense traffic congestions have become one of the city’s main problems. The public transport system cannot cope with the large population, which results on overcrowding, infrequent and unreliable services, discouraging people from choosing buses, BRT or railway as their means of transportation. On the other hand, sidewalks are constantly being reduced to create space for the motorized traffic, making it unfeasible to walk from one place to another. Also cycling is practically inexistent, representing 0.05% of everyday trips on the city, especially due to the lack of bike paths and to the region’s hilly topography.

In order to try to mitigate the problem, the City Administration has come up with different policies and plans to allegedly reduce the traffic. However, their strategies show conflicting priorities, as they try to both accommodate cars through new road infrastructure and increase the capacity of public transport. With the construction of the second and then the third bridge, it becomes obvious that the traffic has been moving from one bridge to the other, and as you create more spaces for car, more cars appear, and traffic gets worse.

RE-ASSIGNING VALUES IN URBAN SPHERE

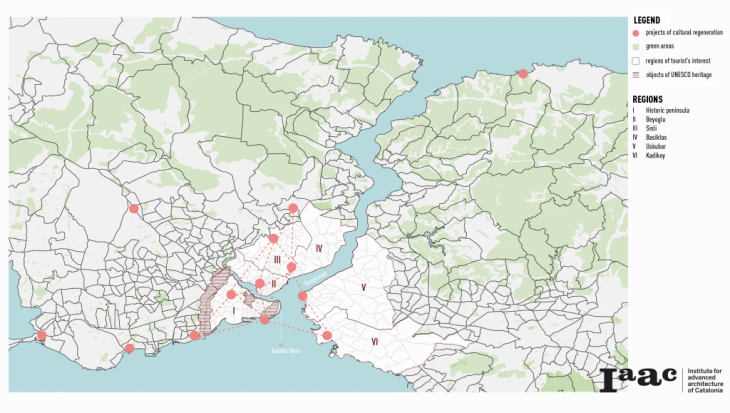

Istanbul Historical Peninsula is one of the rare settlements in the world that contains many structures from various religions, cultures, and communities that coexist in this geography. Four regions even were included in the UNESCO World Heritage List. Despite the fact, there is a high density of historical and cultural objects; most of them are segregated from each other forming clusters of two-three buildings or complexes but without general connectivity. This territory has a great potential for development as far as it also includes plenty of green spaces and access to water.

RE-EVALUATING GREEN SPACES & CONNECTIVITY

With its history of over 2500 years, Istanbul had become an important multifunctional agglomeration because of its establishment in this strategic location where land meets the sea.

Thracian side – comprising the historic and economic centers, surrounded by the Marmara Sea – has the biggest amount of cultural regeneration projects in the Istanbul Metropolitan Area. The distribution of this kind of campaigns shows people’s special interest in these territories and their cultural and historical values. While the economy became export-oriented and the significance of tourism as one of the main income generators increased, this region also became a center of attraction with its six main touristic regions in the central part of the city including UNESCO World Heritage areas.

On the contrary, most of the natural values and green areas are located on the Asian, Anatolian side surrounded by the Black Sea. This kind of division into two parts also shows a lack of connectivity and irregular spreading of values inside Istanbul.

RE-THINKING URBAN GROWTH TOGETHER WITH BRIDGES

Although the effects of the 3rd bridge on the spatial development of the city have been mentioned many times until this point, the risks associated with this retainable development have not yet been discussed.

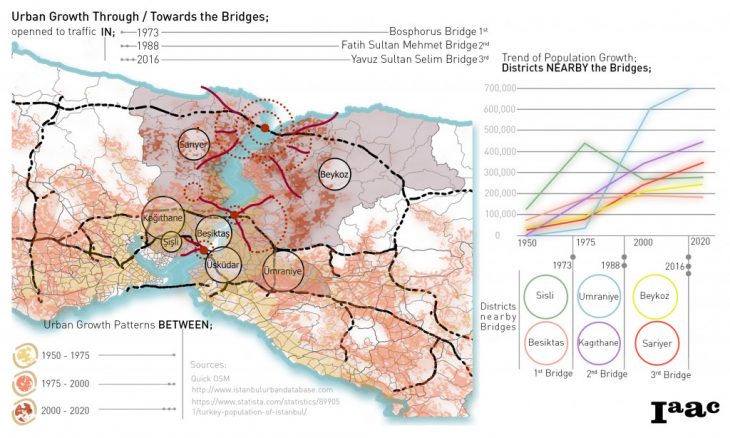

To conceptualize those risks and to make an analytical evaluation, the trend of urban growth through and towards the bridges is worth to consider. To do that, the information gathered on “when” these 3 bridges in the city were open to the traffic; the first one opened in 1973, the second one in 1988 the third one in 2016. Following this and in order to observe how the city grew, three periods have been defined strategically, in which the bridges have gradually been constructed. It is obvious that the population moves around the central locations or districts nearby the bridges through years. The ones which can be recognized in darker background are the metropolitan districts getting widely affected from the bridge constructions. The graph shows the trend of population growth in the districts nearby the bridges to better clarify the excessive increase at specific urban areas which was led by the opening of each bridge.

RE-CONSIDERING ISTANBUL

In order to address the main challenges of Istanbul, a set of strategies were proposed. Firstly, to connect the isolated green spaces and historical/cultural clusters through the creation of green corridors with pedestrian infrastructure and leisure areas. These green corridors or connecters are also linked to the coastline, creating a continuity of public spaces throughout the city. In addition to that, two new routes of Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) are proposed: the Outer Ring Road, which aims to lead prospective urban development to the outer parts of the city, through the expansion of public transport systems, whereas the Inner Ring Road aims to reduce the traffic congestion by improving the public transport system and provide more mobility to the downtown. Moreover, a change on the use of the third bridge – Yavuz Sultan Selim – is proposed, maintaining only half of the lanes for the cars, and leaving the other half for the BRT lanes and for pedestrians. The main idea was to reduce the space for the cars, giving it back to the people.

Re-considering Istanbul is a project of IAAC, Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia developed at Master in City & Technology in 2020/21 by students: Arina Novikova, Laura Guimarães & Sinay Coskun, and faculty: Manuel Gausa, Nicola Canessa & Giorgia Tucci.