The role of quantitative and qualitative data analysis in urban planning

INTRODUCTION

In the last two decades or so, many cities desired to reach the status of “smart city” and technology is what allows a city to become “smart”. High-tech companies lead local governments to adopt their technologies in the physical infrastructure of their cities, such as in transportation, energy supply and management, but also in terms of security or offer of services, just to give a few examples and show instead how the more human point of view has been set aside.

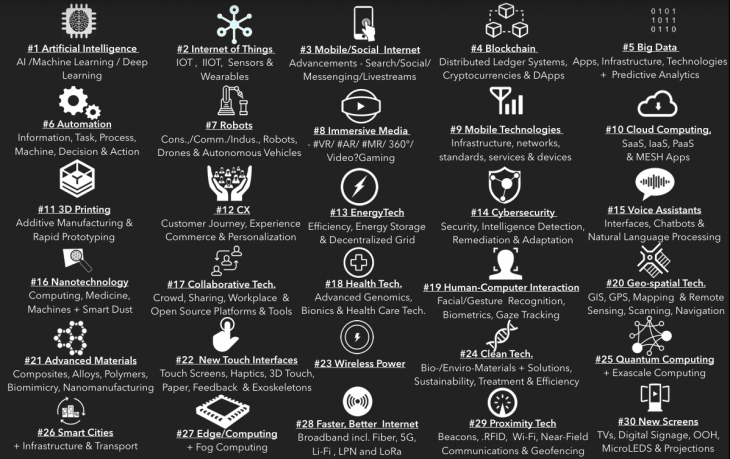

In more recent times new technologies at the service of the city arose: big data, Internet of Things, artificial intelligence, blockchain and data analysis are the most debated in the literature and beyond. They are promising, but like all technologies they are only tools, it is their use that makes the difference.

In the last few years we have seen a change in the trend of smart city objectives, with a greater focus on civic and public participation of citizens in the government networks. A model now known as “smart e-governance” (Robinson et al., 2015). As in the case of the city, the use of the adjective “smart” indicates the deep connection with information and communication technologies, that in this case refers to the direct empowerment of citizens and enables new forms of participation and engagement of city inhabitants in the processes and mechanisms of the local or central government.

The role of people became central and crucial in this process of digitization, because if initially technology was the strategy to initiate top-down decisions, now it can embrace a bottom-up approach, incorporating citizen voice in decision making and moving from a techno-centric to a human-centric vision and big data are the tool that can join city and citizens.

The 30 technologies of the next decade. Source: Moffit S. ? Wikibrand.

NOT ALL THAT GLITTERS IS GOLD

The purpose of all technological innovations has always been to offer efficiency and improve the quality of life of people, but this has often brought with it darker sides. One of the latest and main successes of ICT technologies has certainly been the ability to approach people when it was not possible to do so physically, but even though we are more interconnected, it causes more interaction difficulties, solitude and sadness (Collier, 2019).

With the passage of time we have more and more access to a wide range of instruments (computer, smartphone, sat navs, wearables, etc.), which together with an internet connection, allow tech companies to collect a lot of information about each of us, while using their applications. So, another huge threat arises and it is our personal privacy.

New technologies can also have effects on the social, economic and psychological level of human beings. If we think about automation, workers can be afraid to be replaced by machines, robots or autonomous cars, while the rapid changes that technological innovations can bring force people to adapt themselves to new occupations and opportunities, sometimes with loss of income or risk of unemployment.

Issues could also arise when we try to use technology to create cities more inclusive and responsive to people. Society is divided between those who have the access to resources and those who have not, usually the poor, the elderly and those who are on the margins of society. They are disconnected from the main stream of users, therefore technology cannot be isolated from the social spheres and influences. This is inevitably related to the complex structures of urban environments and technology could be a great enabler for engaging with people, but “it is never the solution, therefore it cannot replace the social capital of cohesion, mental and physical activities among human beings” (Weinstein, 2020).

The two faces of technology represent the challenge that all professionals committed to working with the city have to face, moving on the line between the possibility to enable accessing to education and information, limiting social gaps, and the risk of growing gaps for the lack of infrastructure and lack of digitization skills.

BIG DATA ANALYSIS AS POINT OF CONTACT BETWEEN CITY AND CITIZENS

Practitioners in the “smart” urban sphere are increasingly recognising the need for a more human-centered approach in designing and governing the city and social innovations, sharing economy, open database and transparency are just a few examples that can engage citizens (Weinstein, 2020). In particular, data collection and analysis can represent a means to close the gaps between top-down policies and bottom-up initiatives.

Collaborative and creative solutions can address applications for areas like education, health, energy, law, manufacturing, environment, safety and considering also real-time solutions, agriculture, transportation and crowd management could be similarly involved in this process (Bertot & Choi, 2013).

There are different methods that could be adopted in the research process and the main classification is in quantitative and qualitative research. In the first case the analysis is conducted on quantifiable properties and their relationships for certain phenomena, while on the other side the qualitative research is used for understanding human behavior (Zhu, 2012). Therefore, when talking about the complexity of cities, it is quite obvious that both methods are useful and in the following section some examples of how to handle these two types of data will be illustrated.

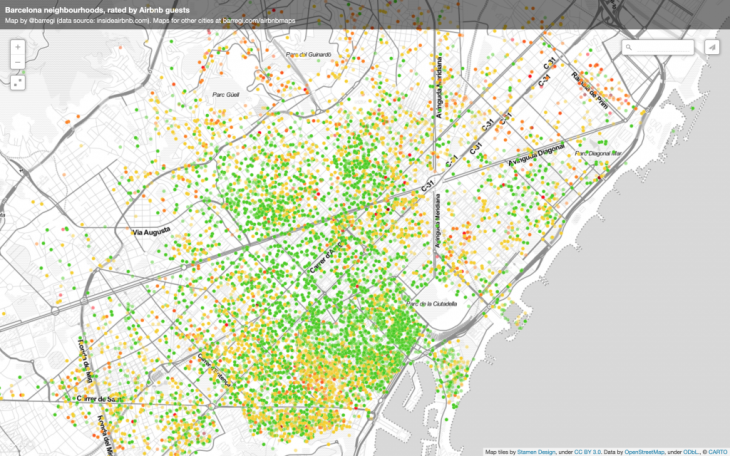

City maps from tourists’ feelings, Barcelona. Source: Arregi B.

QUANTITATIVE -vs- QUALITATIVE

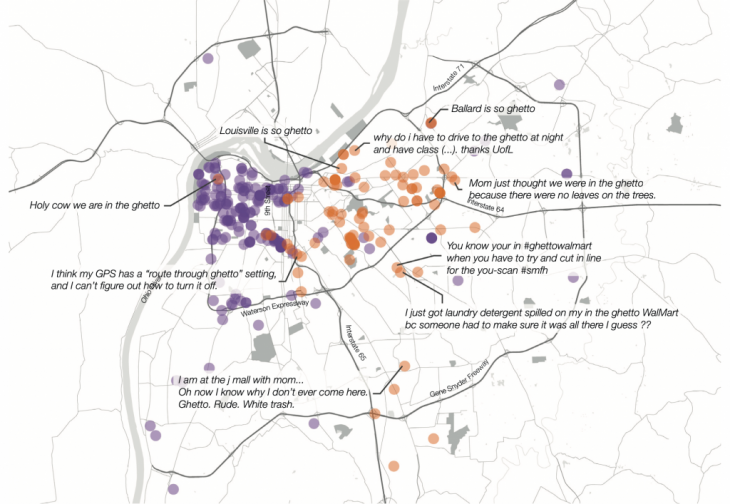

The main purpose of data science is to reach functionality and for that it is necessary to simplify phenomena into numbers. The possibility to collect an increasing and differentiated number of data in the urban context pushes data analysts to deal also with qualitative data that need to be translated into quantifiable parameters. So, even if quantitative analyses are usually preferred (because they allow statistical analyses), and qualitative data are harder to handle because of the lack of structure, their contribution is similarly important because they can add a more human dimension to the study. In qualitative research it is necessary to define a proper context and a definition of the problem, in order to be able to answer the correct questions.

An essential part of studying cities is the necessity of combining these two types of analysis, in order to give a kind of human touch to quantitative data and a comparability basis to those qualitative. It is also always good to keep in mind that the collection and analysis of data are based on choices, therefore it is important to make people aware of the possibility of bias, that could be removed mathematically but risking to lose a huge amount of data and thus invalidate the research, so a good practice could be to try to make explicit what the bias is, providing de facto scientific soundness to the work.

On this trail, sometimes, the analysis of public space could not correspond to the expected conditions, because people can use spaces in different ways and then it is possible to find a variable that was missing and that designer did not understand people’s desire.

In studies of qualitative data there is an interest in driving the analysis by multidisciplinary groups, as a consequence of the complexity of the city. Different perspectives can create methodologies to better understand the different factors involved. Something that became a constant in this analysis is the definition of possible users and the setting of quantitative parameters that can affect spaces and allow comparison. For example for noise or temperature, it is necessary to ask users the correct questions, helping to correlate the variables and starting to design and adapt spaces for the different users considered and leave the possibility to implement future analyses in other contexts, keeping track of the specificity of each place.

Tweets referencing ‘ghetto’ from West End and East End users. Source: Shelton et al. (2015).

CONCLUSION

From the methodological point of view, it is important to have an adaptable framework that can keep track of specificities and allow the comparison and the replicability of studies. It is well known that each context has its own characteristics, but it could be easily comparable through the analysis of quantitative data, while on the other hand qualitative data can help to highlight even more the peculiarities of the place.

Data analysis is a powerful tool as far as it is related to the sensitivity of decision makers. This approach can heavily influence the way we design our cities and this digitization process can link and connect together aspects that are either qualitative or quantitative, or that belong to different disciplines. When we look at cities we are not only talking about buildings, transportation or people. It is very important to reach the ability of making connections between complex aspects of different natures and the digitization process could be crucial. It can help to make visible those layers of the city that people usually do not see, like the impact of economic or energetic choices. A system that goes beyond architecture and that can empower people.

Layers of complexity envelop our cities and beyond, bringing us to the point to rely on technology to make cities more accessible and more human.

REFERENCES

Al Nuaimi E., Al Neyadi H., Mohamed N. et al. (2015), Applications of big data to smart cities, J Internet Serv Appl, 6, 25.

Arregi B. (2018), City maps from tourists’ feelings.

Bertot J.C., Choi H. (2013), Big data and e-government: issues, policies, and recommendations, Proceedings of the 14th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, ACM, pp. 1–10.

Collier C. (2019), Lonely people in big cities: How technology is both creating and solving the isolation crisis, Smart Cities Connect.

Gaber J. (1993), Reasserting the importance of qualitative methods in planning, Landscape and Urban Planning, Volume 26, Issues 1–4, pp. 137-148.

Moffitt S. (2018), The Top 30 Emerging Technologies (2018–2028).

Robinson L., Cotton S.R., Ono H., Quan-Haase A., Mesch G., Chen W., Schultz J., Stern M.J. (2015), Digital Inequalities and Why They Matter, Information, Communication & Society, 18(5), pp. 569-582.

Shelton T., Poorthuis A., Zook M. (2015), Social media and the city: Rethinking urban socio-spatial inequality using user-generated geographic information, Landscape and urban planning, 142, pp. 198-211.

Weinstein Z. (2020), How to Humanize Technology in Smart Cities, International Journal of E-Planning Research, 9 (3), pp. 68-84.

Zhu H., Madnick S. E., Lee Y. W. & Wang R. Y. (2012), Data and Information Quality Research: Its Evolution and Future, Composite Information Systems Laboratory (CISL) Sloan School of Management, Room E62-422, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, MA 02142.

The Ultimate Paradox: Humanizing Cities through Technology is a project of IAAC, Institute of Advanced Architecture of Catalonia developed at Master in City and Technology in 2020/21 by students: Matteo Murat, Ivan Reyes Cano & Miguel Angel Tinoco and faculty: Mathilde Marengo