INTRODUCTION

The research presented here as part of the Expansive Theory seminar, investigates the question of whether architecture can enhance and empower the commons. In Architecture for the Commons, Jose Sanchez demonstrates how participation has changed throughout architectural history and evolved. Sanchez shows that more power can be given to the commons through various types of technological tools. Our hypothesis is therefore centered around the idea that commons can be empowered through participatory processes that instrumentalize apps under Marshall McLuhan´s retribalization.

Fig 1. Archigram Cities, Drawing Architecture Studio, “Walking”, 2020

The term “commons” was largely understood to indicate the natural resources that were freely accessible to society as a collective. Today, the challenge has migrated more and more toward copyrights and intellectual property. In Architecture for the Commons, Jose Sanchez builds a perspective closer to the labour that designers engage with, as well as the value, knowledge and expertise that live in the networks of education, ideation, collaboration and development, even if buildings do not reach materialization. Material and immaterial common-pool resources and the infrastructure of digital networks are designed and envisioned to decentralise and distribute the power back to the commons.

CONTEXT

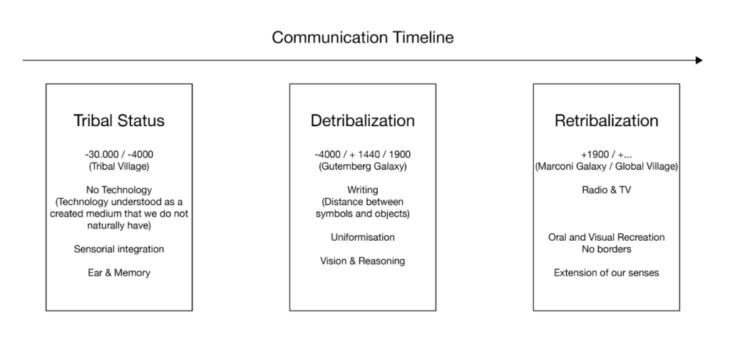

Marshall Mcluhan was a Canadian philosopher with foundational work in media theory, which was crucial in transforming the way we saw the impacts of different media. He wrote the book Understanding Media, where he coined the phrase “the medium is the message”:

“This is merely to say that the personal and social consequences of any medium—that is, of any extension of ourselves—result from the new scale that is introduced into our affairs by each extension of ourselves, or by any new technology.”

Fig 2. Marshall McLuhan: Tetrad of Media Effects, 1988

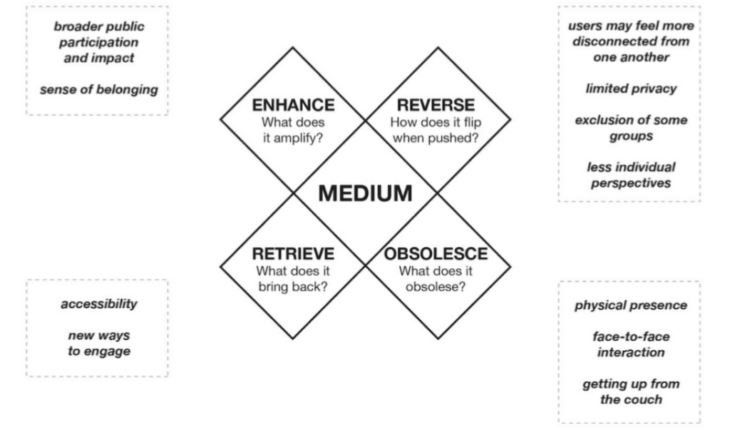

McLuhan’s Tetrad was therefore used as the framework to analyse mobile apps for participatory processes.

Enhance:

They amplify opportunities for the broader public to participate and have an impact, along with a sense of belonging.

Retrieve:

They bring back accessibility and new ways for people to engage that weren’t available without smartphones.

Obsolesce:

They make physical presence, face to face interaction, or getting up from the couch unnecessary.

Reverse:

On the flipside, users may feel more disconnected, have limited privacy, some might actually be excluded (ones that don’t have or can’t use a smartphone), and the individual perspective could feel diluted.

Retribalize

verb […]

2 To bring about a return to a collective rather than individualistic mode of behaviour and thought, due to the influence of telecommunications and electronic media.

(Lexico.com, Oxford Dictionary)

Fig 3. Marshall McLuhan: Understanding Media, 1964

The tribal town was a participatory place that involved all its inhabitants in the creation of its commons. The oral word as a means of communication stimulated the ear before sight. It involved the listener sensorially and emotionally and thereby integrated him into the group of belonging.

In the tribal village, the only possibility of transmitting and accumulating experiences was by doing so in the restricted space that was represented by the memory of the group. Construction was a collaborative process in which the tribal network passed on its experience to each other.

According to McLuhan human society underwent a Detribalization through our changing mediums of communication. The written word creates distance and uniformisation and puts vision and reasoning above sensorial experiences. Top-down approaches in construction were the result. Further disparities in the distribution of the commons were created, as the illiterate population was not able to participate in the discourse.

Through modern technology and media, communication underwent a retribalization since the beginning of the 20th century. Sensorial experiences have been gaining importance once again. We are more connected in a global and borderless village.

HISTORICAL TRAJECTORY

The design of the indigenous and localized structures were centred around the users and were constructed through the collective memory and effort of the group.

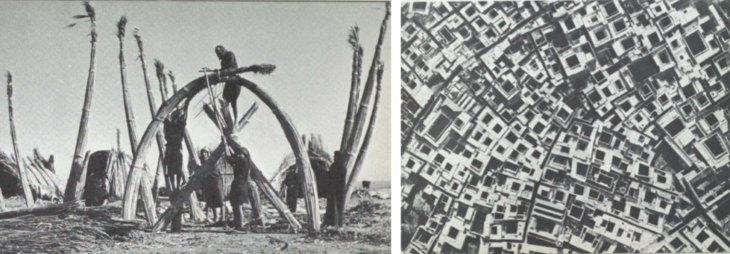

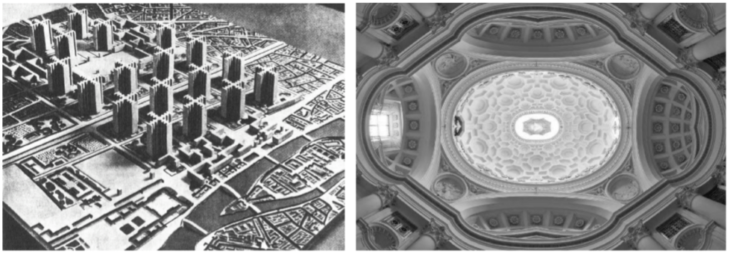

Fig 4. Architecture without Architects: Indigenous Grass Structures Fig 5. Architecture without Architects: Old Town Marrakesh

The old town of Marrakesh and the Agora of Athens also evolved with respect to the users’ requirements and no central planning. Until the 20th century architectural planning was mostly centralized. Baroque Churches like Iglesia de San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane are an extreme example of that. A single architect was given full control, while perfection of the geometry was the most important goal. Modernist approaches like the Voisin Plan for Paris are representative of how the architect was the main vector influencing society.

Fig 6. Le Corbusier: Voisin plan for Paris, 1925 Fig 7. Iglesia de San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, 1636-1646

Fig 6. Le Corbusier: Voisin plan for Paris, 1925 Fig 7. Iglesia de San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, 1636-1646

During the 20th century there was an ascending number of projects being developed that aimed at fulfilling its user’s needs through participatory processes.

Archigram turned away from conventional architecture to create novel technology-based environments. They envisioned networked cities, hybrid products and interaction design. An urban environment saturated with connected sensors that together could produce torrential amounts of data. Likewise, Superstudio envisioned a machine city that takes care of everything. Citizens are living on a conveyor belt, while all their needs are being taken care of by the machine.

The Generator, by Cedric Prize, attempted to create an adaptive house, similar to visual scripting. The Oregon Experiment tried to provide guidelines for participation in design. However, like the utopian visions of Archigram and Superstudio, they ultimately fell short due to the technological limitations of the time.

STATE OF THE ART

Machine learning, wearables, smart cities, along with apps, video games, and blockchain have begun to shape participatory processes. These technologies engage with information-rich environments and present diverse opportunities to enhance human participation and progress towards a distribution of commons.

Smart cities utilize interactions and social scenarios to allow the built environment to be restructured through collective participation of city inhabitants. This is a new nature of human machine interaction that could be structured through people’s behaviours and could be an impetus to build more equitable cities. Similarly, wearable and augmented vision systems also possess strong qualities for performance, sociality, interactivity, and participation. When used to obtain biomedical data of patients, connections can be created between wearable devices and sensor systems in buildings and cities.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning, while still at a gradual encounter with participatory processes, have made available building data and codes, allowing inhabitants of the built environment to have the possibility to input data and inform a design. Likewise, games and apps could allow users to make improvements to a virtual copy of their own cities or accumulate game-points for a specific urban project being proposed.

Moreover, blockchain allows multiple agents to share information, interact with one another while having access to all published information on the platform. This decentralized management results in a more transparent bottom-up approach.

CASE STUDY 1

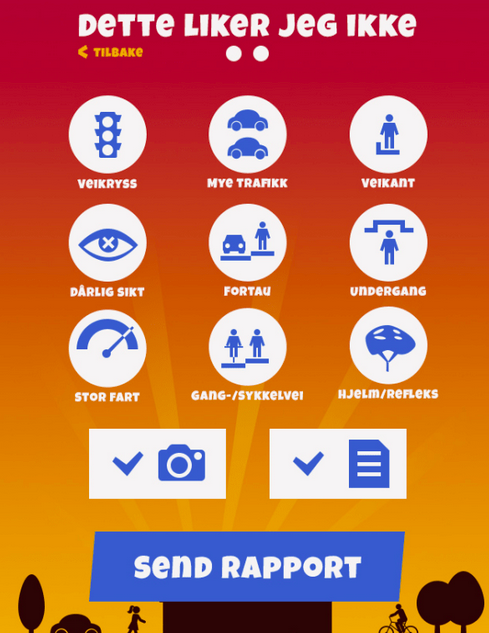

Traffic Agent in Oslo, Norway is a mobile application developed by the municipality of Oslo in order to increase the amount of feedback related to road maintenance and safety. In an initiative to improve walking or biking to school, the app was distributed to primary schoolchildren. It tracks their movement by GPS, they are called “spies” in the game, while a voice conceptualized as a “secret agent” guides them through the process of reporting unsafe crosswalks on their route to school.

Fig 8 – “The Urban Mobility Observatory.” Eltis, 15 Sept. 2021

The app retrieves feedback and can enhance participatory processes by allowing ease of access. It obsolesces long wait times of phoning into a municipality, and amplifies the voices of children, who are rarely consulted for feedback on city planning. However, the lack of open information on reported issues maintains this app as having a centralized power structure, where voices are funnelled through a medium which may or may not respond to them.

CASE STUDY 2

The city Zug in Switzerland has an app called “Uport” where they give each citizen a dedicated identification number. The app is hosted on blockchain technology. The app intends to create a streamlined channel of information and voting history about a person. This could create a system where the amount of information attributed to someone is overly centralized, some privacy may be lost due to the reduced amount of government entities which control citizen data. Another possible problem is the isolation of older citizens who are not familiar with technology.

Fig 9. “Zug Digital ID” Uport, November 17, 2017

CASE STUDY 3

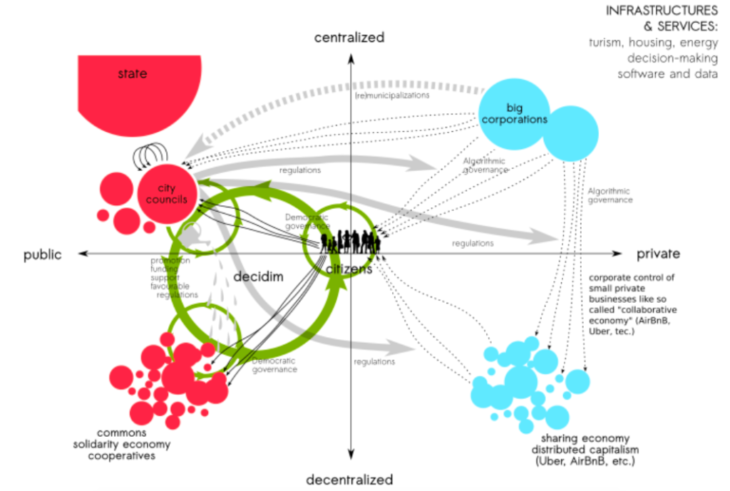

Decidim is an open-source platform that allows citizens, organizations, and cities to connect on various processes from strategic planning all the way to networked communication. It also allows anyone to collaborate through the meta-decidim community to propose features, or report any errors. This app in particular brings us closer to retribalization in the sense that it´s connecting citizens to each other as well as city processes, allowing them to have a say in shaping their community and at the same time the platform itself

Fig 10. Barandiaran, de Xabier. “What Is Decidim?” Xabier E. Barandiaran, 27 Apr. 2018

However, the amount of people participating is not truly representative of the greater commons. On Decidim, some projects only have at most a few hundred people following them.

THE FUTURE OF COMMONS

Machine learning, wearables, smart cities, apps, video games, and blockchain: will further shape participatory processes, by facilitating interaction and engaging with information-rich environments to progress towards a more equal distribution of commons. Although these technologies connect in many ways, they also disconnect from face to face interaction. Their reach and use will determine their success and implementation, and the level of participation and engagement. One might also question how meaningful the participation and real world impact truly is on an individual level.

List of Sources

Figure 1 – Archigram Cities, Drawing Architecture Studio, “Walking”, 2020

Figure 2 – Marshall McLuhan: Tetrad of Media Effects, 1988

Figure 3 – Jordi Vivaldi Piera Lecture Slide, 2021, from: Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media, 1964

Figure 4 –Architecture without Architects: Indigenous Grass Structures

Figure 5 – Architecture without Architects: Old Town Marrakesh

Figure 6 – Le Corbusier: Voisin plan for Paris, 1925

Figure 7 – Iglesia de San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, 1636-1646

Figure 8 – “The Urban Mobility Observatory.” Eltis, 15 Sept. 2021

Figure 9 – “Zug Digital ID” Uport, November 17, 2017

Figure 10 – Barandiaran, de Xabier. “What Is Decidim?” Xabier E. Barandiaran, 27 Apr. 2018

List of References

Alaimo, Stacy. Exposed. Environmental Politics and Pleasures in Posthuman Times. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Braidotti, Rosi. The Nomadic Subject. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Braidotti, Rosi. Posthuman Knowledge. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2019.

Braidotti, Rosi. The Posthuman. London: Polity Press, 2013.

Braidotti, Rosi. “Writing as a Nomadic Subject”, Comparative Critical Studies, no. 11.2-3, 2014.

Bratton, Benjamin. The Revenge of The Real: Politics for a Post-Pandemics World. London: Verso, 2021.

Bryant, Levi R. Democracy of Objects. Michigan: Open Humanities Press, 2011.

Chalmers, David. “Strong and Weak Emergence.” In The Re-Emergence of Emergence, edited by Philip Davies and Paul Clayton. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Jinha, Y. “Does State Online Voter Registration Increase Voter Turnout?” Social Science Quarterly. 2019.

McLuhan, Marshall, and W. Terrence Gordon. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Gingko Press, 2015.

Urban Retribalization – Mobile apps as tools for city design is a project of IAAC, Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia developed at Master in Advanced Architecture in 2021/2022 by students: Solene Biche Cais, Meagan Enright, Akshay Madapura, Alessandra Weiss, Luca Wenzel, Yue Wu Faculty: Manuel Gausa, Jordi Vivaldi